- The UNC’s plans for digital transformation as outlined in their “minifestos,” highlighting both generalities and specific initiatives.

- The new government should assess and potentially continue ongoing digital projects from the previous administration, emphasizing the long-term nature of technology development.

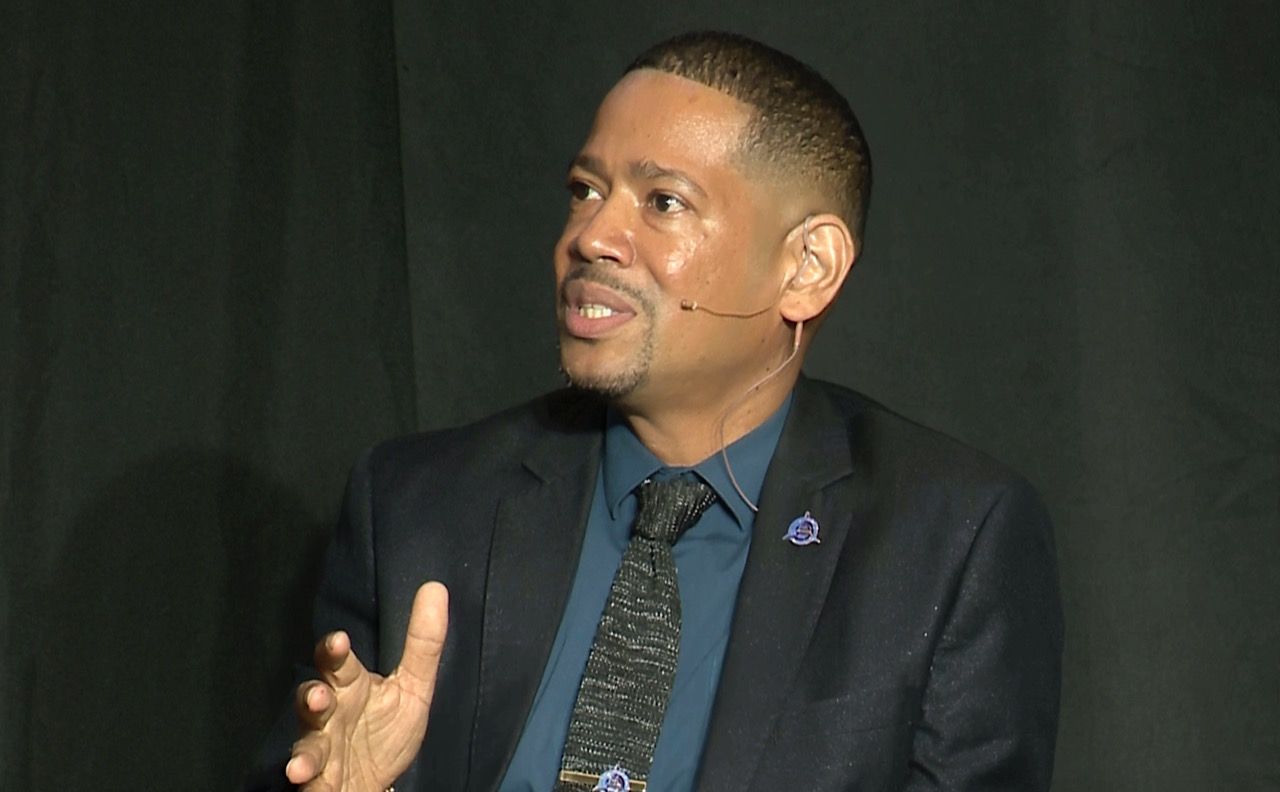

- A strong leader, like Professor Ken Julien in the energy sector, is needed to drive change and oversee the execution of digital transformation initiatives.

Above: Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar.

BitDepth#1509 for May 05, 2025

It’s early days for your new government, Prime Minister, and your first emphasis is likely to be on establishing its leadership presence. Your first appointments will probably address the hot-button issues of crime and the economy.

The UNC’s “minifestos,” bullet point summaries of your plans after taking office offer the best guide of your administration’s plans for digital transformation after forming the new Cabinet.

In those documents, there are both wild generalities, obvious solutions, initiatives already in development by the outgoing government and some misunderstandings about how digital initiatives should inform the new government’s plans.

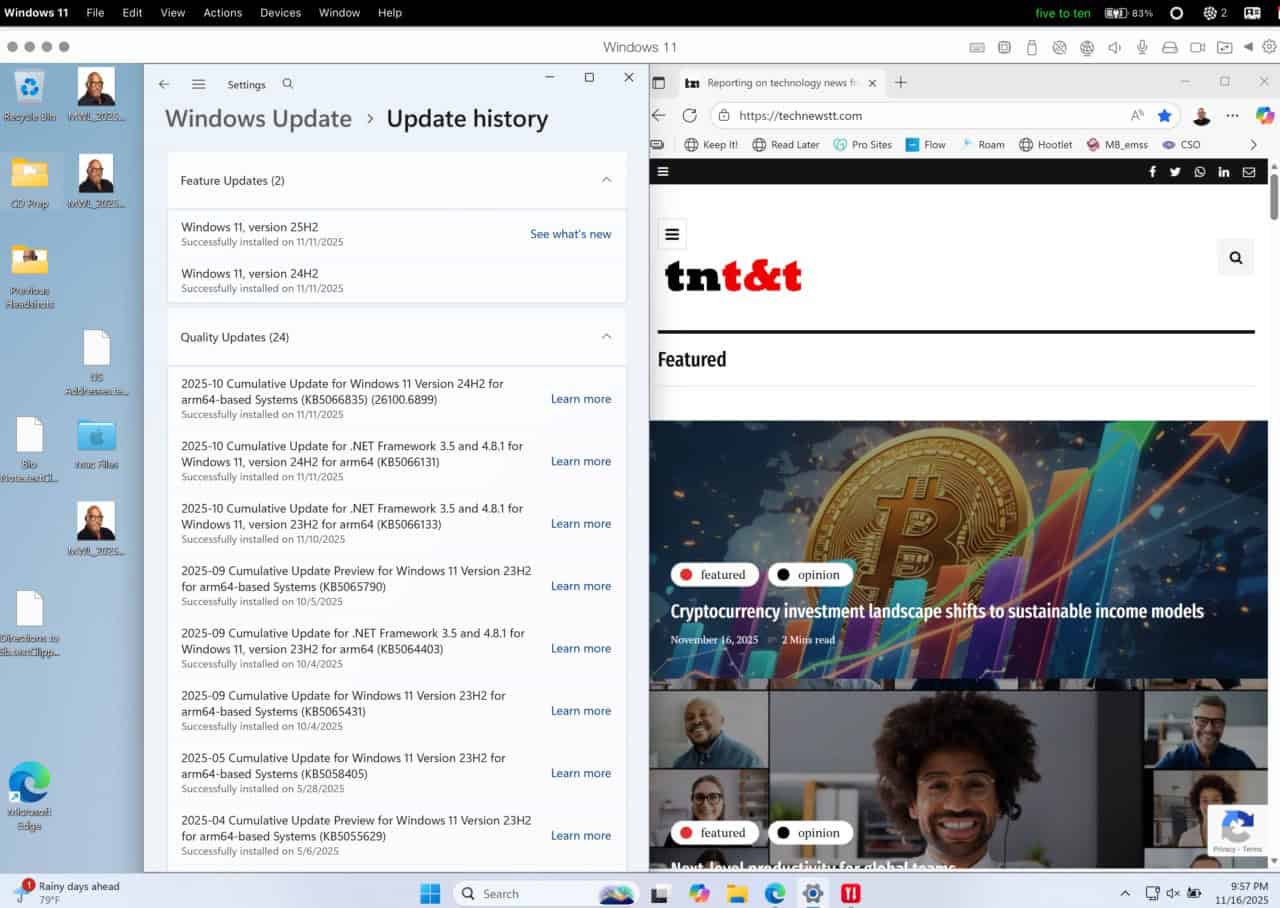

There is a long standing tradition of “new broom” efforts after a change in government, but technology development is a long runway effort, so your incoming government should take the time to assess the projects that are already underway.

While nobody would accuse the outgoing Minister of Digital Transformation of offering a coherent, transparently communicated and routinely updated roadmap of the ministry’s work, there are several projects in development that it would be needlessly destructive to derail.

Unlike the quick fix of repairing a stretch of roadway that rewards inconvenience with tangible improvement, TT’s digital development will be measured in years, a timeline likely to be extended through governance and procurement restrictions.

At least two often referenced, but vaguely articulated ministry projects, the improvement of data interoperability in government and the implementation of an electronic ID are critical pillars necessary to bring some of the UNC’s manifesto plans into reality.

In the UNC’s anti-crime manifesto, for instance, the plan to pursue “electronic data access in all police vehicles,” only works if there is an efficient capture process for relevant information, a secure system for storing data and a robust data encryption regime for transmitting it.

Making that happen will also demand a sweeping overhaul of the outdated police report book system, which locks live crime data into largely inaccessible hard copy, itself requiring another tier of digital infrastructure and hardened cybersecurity.

Digital benefits will come from a commitment to interlocking data systems, which improve efficiency, increase transparency and, eventually, deliver tangible improvements to citizen’s lives.

What the technology sector in governance has long needed is a czar.

Professor Ken Julien, operating with the clear blessing of Dr Eric Williams and the long runway of continuous PNM governance fulfilled that role for the energy sector.

Dr Williams would not have known how to realise his dream of greater control over the exploitation of this country’s natural resources, but he found someone who did.

Dr Julien did not effect that change – which led to two major booms in the economy – on his own.

He gathered around him trusted and knowledgeable lieutenants who guided the planning, oversaw the execution and changed the fortunes of the country.

Hassel Bacchus was no Ken Julien. We’ll never know whether he might have been, because he never enjoyed the freedom of action, the scope of control, or the time that Julien had when he reengineered the extraction of oil and gas in this country.

Bacchus must have wrestled mightily with a determinedly siloed public service infrastructure infested with petty rivalries and driven by a lethal mix of lethargy and ruthless personal advancement.

Picture then, Prime Minister, an elaborate design of dominoes, each lined up in front of the other, just waiting on the gentle tip that will create an accelerating revelation of potential as one domino topples into another.

Then imagine the frustration when one domino, determinedly out of alignment with the others, fails to pass along that momentum.

Then imagine it happening year after year, from 2003 to 2025.

Nobody with the required skills, commonsense or emotional strength could continuously bear witness to an interminable replay of that tragedy.

So we have a logjam of dunderheads in leadership roles in the technology governance sector. There are people who should clearly go, particularly the unscraped, useless barnacles accumulated by decades of failed attempts at digital governance.

But there are also many who can harness existing efforts to engines of completion.

Poor leadership choices are why our best technology minds left government for the private sector or left the country entirely.

Leaving us here, five years after the creation of a dedicated digital transformation ministry, and after more than two decades of stumbling to implementing technology in governance, stuck at the starting blocks of real change.

But we aren’t actually in as bad a place as it seems.

Some of these projects are useless PR BS. Some are in needless conflict with each other. Some are critical components of any real-world effort to bring digital services to the public.

Politics is all about navigating grey areas. Technology is all about bits. Some have a value; some have none.

Mrs Persad-Bissessar, you have had power. At 72, it would not be unreasonable for you to seek opportunities to deliver legacy in office this time around.

Digital transformation would be the best place to start to achieve many of your stated goals.