Above: Illustration by kosecki/DepositPhotos

As the education stakeholders praise the return of the student laptop program, it’s important to understand how success is gauged. The issue with technology is that metrics are hard to come by, and in the context of education, the results aren’t seen for about a decade.

Off the bat, since the initiative was first introduced the last time we had the same prime minister (2010-2015), what metrics do we have? Everything reported seems to be about how people feel about it, which is good, but how does one measure success?

Last week, I found myself speaking with someone who was one of the recipients of such a laptop. She’s employed as an administrator at a private company, and she uses a computer every day at work. We could call that a success, but the job market impacts that, as does the economy. Her ‘success’ – and she’s not happy with where she is at – could be an outlier.

How many people who received laptops through the program are presently using their skills?

Technology has shifted in the last 10 years. The average attention span of people is roughly 47 seconds, social media companies are fighting for that in the attention economy even as the information economy has gone into what could be described as digital feudalism.

Where did the training data for AI models come from? What biases does a generative AI have?

We get ‘free’ services at the cost of our information, so much so that it’s easy to hypothesize that Waze has more information on traffic in Trinidad and Tobago than local ministries. Facebook, too. And people scroll and scroll, interacting with posts that they like, while the government doesn’t seem to have figured out that data sovereignty is important.

Yet, exposing young minds to technology is supposed to be a good thing.

A Fractal Nature

It’s good to expose young minds to the Internet, to be able to find information, and yet it comes with the danger of distraction. From pornography to amusing videos of animals, from TikTok trends to Facebook algorithms, we live in a world of distractions.

A young mind that can learn how to deal with the distractions while being productive is like tempered steel. A young mind that doesn’t learn to deal with the distraction succumbs, to become a battery for a foreign company’s revenue stream. It’s a dangerous game, but it does need to be played for the good of the economy, and for their own betterment.

How they are exposed determines the results. Flinging laptops out of a Ministry comes with dangers such as:

- Software subscriptions: Microsoft loves vendor lock-in. Teach young minds to use their products and they’re guaranteed a bias toward their products, despite offerings by the open source community that spends almost nothing on marketing in comparison.

- Microsoft products need new hardware more often than Linux. It’s effectively a hardware subscription model.

- Generative AI: Do teachers know how to weed out homework that was done by ChatGPT, Grok, and others? Those turn into subscriptions as reliance on them increases. Will teachers need AI to catch AI? Another subscription.

- Access to much information is increasingly paywalled because of scraping of websites for generative AI.

Given Trinidad and Tobago has a foreign exchange problem, which seems an understatement, and that all the subscription models and hardware will require foreign exchange, we have an initial cost and a recurring cost. Who will pay the recurring costs? The government? The individuals?

The Solution

Linux and open source solutions seem the best way forward. No recurring costs for software, and it allows the growth of a community that can support itself when it comes to technology rather than someone learning only a specific company’s way of doing things.

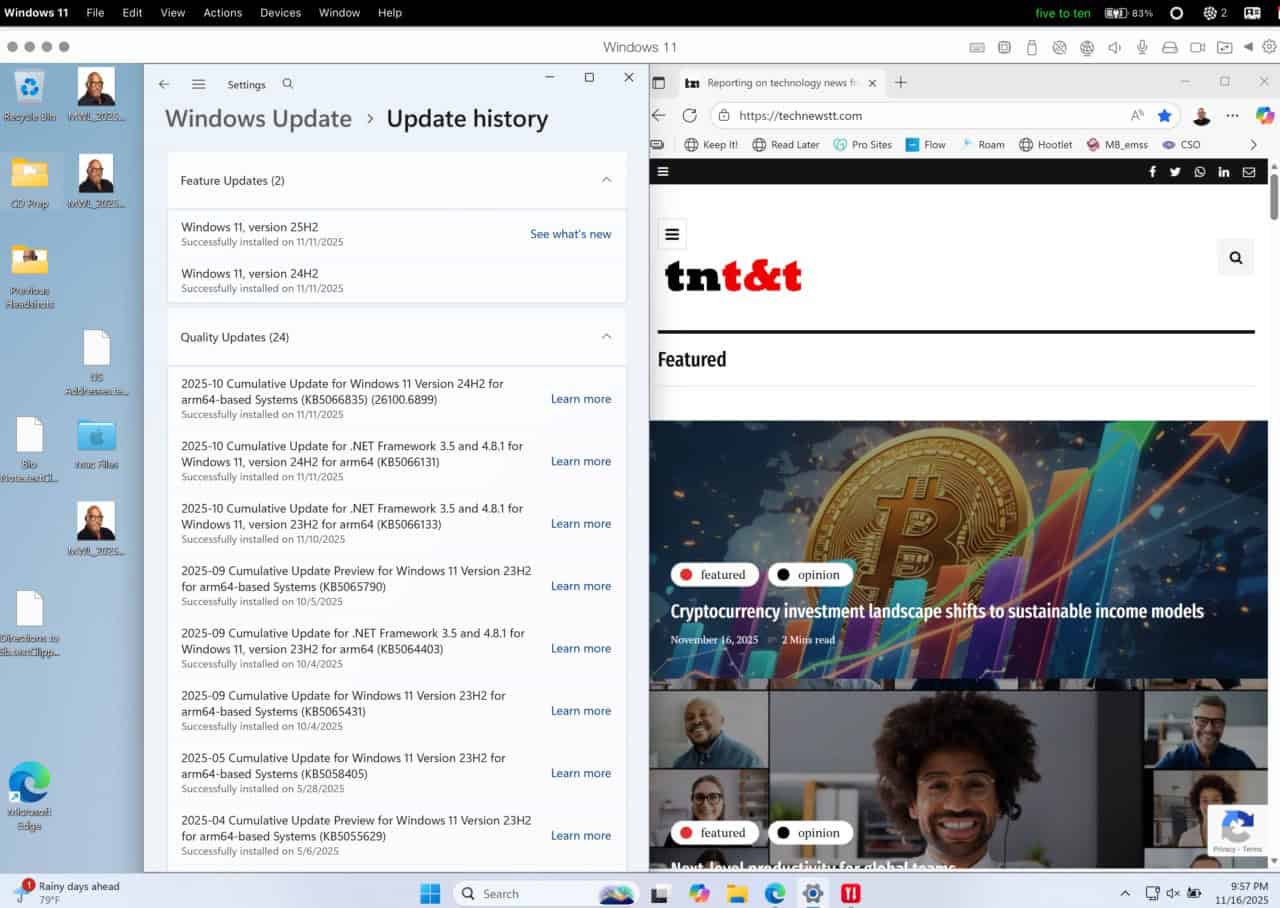

That alone may not reduce the initial cost, but it will reduce the recurring cost. It will extend the life of the hardware, even as Windows 10 support is being discontinued in October of this year.

The growth of a real digital community in Trinidad and Tobago, as the FLOS Caribbean conference in 2003 advocated, has to be built on something that doesn’t require recurring foreign exchange costs and vendor lock-in. The best way forward is through open source, and the people making those decisions need to understand that.

The secret of Silicon Valley success is that it fails, and the failures create more experienced people that help with the next success. The same holds true with anything.

Beyond education, the country needs to pick data sovereignty and true independence over an information economy that takes more than it gives.

Taran Rampersad has over three decades of experience working with technology, the majority of which was as a software engineer.

He is a published author on virtual worlds and was part of the team of writers at WorldChanging.com that won the Utne Award and an outspoken advocate of simplifying processes and bending technology’s use to society’s needs.

His volunteer work related to technology and disasters has been mentioned by the media (BBC), and is one of the plank-owners of combining culture with ICT in the Caribbean (ICT) through CARDICIS and has volunteered time towards those ends.

As an amateur photographer, he has been published in educational books, magazines, websites and NASA’s ‘Sensing The Planet’. These days, he’s focusing more on his writing and technology experiments. Feel free to contact him through Facebook Messenger.