- A teenager committed suicide after being extorted for money in exchange for not releasing their intimate photos.

- Meta removed around 63,000 Instagram accounts in Nigeria linked to financial sextortion scams.

- Professionals believe over a hundred local children in the area have attempted or seriously considered suicide due to cyberextortion.

Above: Photo by zanuckcalilus/DepositPhotos

BitDepth 1538 for November 24, 2025

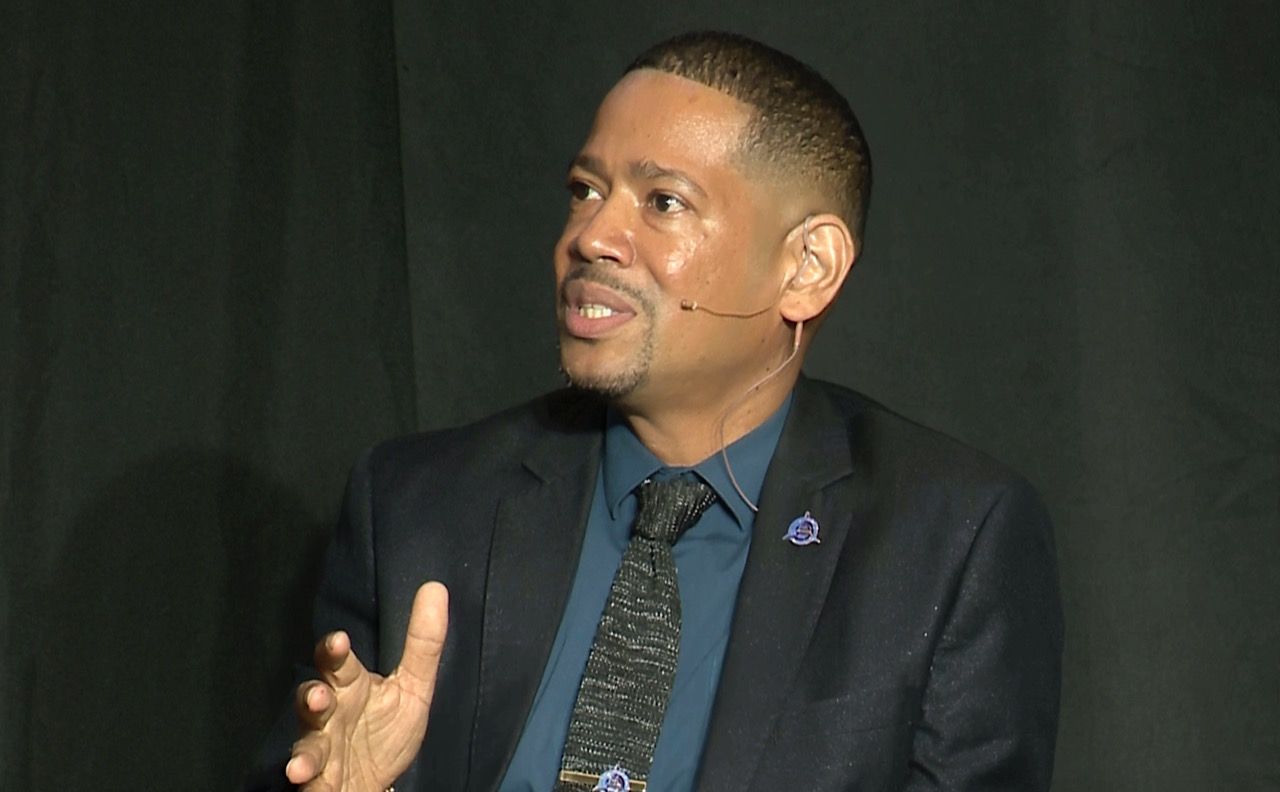

Early this year, Shiva Bissessar mourned the loss of someone he knew, a promising youth still in their formative teenage years.

The child took their own life rather than face the potential humiliation of having intimate personal photographs revealed on the open internet by an extortionist who had won their personal confidence.

So Bissessar investigated what was known about the incident. What he found stunned him.

“The victim was communicating with someone purporting to be their significant other.” Bissessar said.

“We had the device, and we messaged the person to ask them what’s this about? The person on the other end of that conversation continued to try to convince us that they were in a relationship, and compromising images might have been shared of the victim.”

“The perpetrator was acting out a role, saying their boss saw these images and was offended, but x amount of money will fix all that. They continued to try to extort value even after being told that the victim took their life. They sent images that were probably used to pressure the victim and threatened to release them. They were determined to extract value.”

“I talk about these things professionally, and here it was happening in front of me. The messages are something that need to be studied. We need to analyse the messages sent in some of these schemes because there are indicators of where the perpetrator is originating from. They issued a countdown demanding money. The countdown is apparently a West African cyberextortion technique.”

In July 2024, Meta issued a statement on financial extortion scams on its networks.

“We removed around 63,000 Instagram accounts in Nigeria that attempted to directly engage in financial sextortion scams,” Meta stated in a blog post.

“These included a smaller coordinated network of around 2,500 accounts that we were able to link to a group of around 20 individuals.”

“We removed around 7,200 assets, including 1,300 Facebook accounts, 200 Facebook Pages, and 5,700 Facebook Groups, also based in Nigeria that were providing tips for conducting scams. Their efforts included offering to sell scripts and guides to use when scamming people, and sharing links to collections of photos to use when populating fake accounts.”

Teenage children face two key threats while socialising on their smartphones and computing devices. Cyberbullying became pervasive during covid lockdowns, creating a new, anonymous aggressor.

Cyberbullies can be anyone with “bad mind.” They don’t have to be big, or strong, they can destroy with a single shared screenshot.

Cyberbullying is believed to have increased tenfold since lockdowns, but cyberextortion, internet-based sextortion targeting minors, is an external cyberattack.

How it works

Bissessar wrote in 2019 about “digital kidnapping,” the stealing or cloning of an existing child’s identity, then a way to tempt adults and then blackmail them .

The attack vector takes advantage of widespread “sharenting,” the details that parents offer up on social media about their underage children.

Bad actors seek teenagers who are digitally vulnerable because of inadequate security measures and offer potential for financial return through blackmail.

Teens probably won’t have cryptocurrency, but can use gift cards to make blackmail payments.

Key vulnerabilities

A conservative society that frowns on discussing sex with puberty age children, limits formal sex education, ostracises alternative lifestyles and fails to educate children about the potential consequences of sharing intimate images and geolocation information online creates fertile ground for cybercriminals.

Bissessar believes that the only effective response to this kind of cyberattack is to create an accepting environment to discuss personal mistakes. If a child does not believe they can speak with an adult and be heard meaningfully, the criminal wins.

In the case of the dead child whose messages he viewed, Bissessar believes that the child was convinced there was no other way out of the situation.

Emails and phone calls on the matter sent to the Education Ministry and the National Security Ministry’s TT Cybersecurity Incident Response Team were neither acknowledged nor answered.

Privately, professionals with insight into the matter locally believe that there have been more than a hundred incidents over the last 12 months in which children have either attempted or seriously considered suicide because of professional cyberextortion.

Employees of the Education Ministry’s Student Support Services Division are said to be struggling with this targeting of unprepared local teens.

AI enables a bad actor to convincingly alter their voice and live deepfake technology can create persuasive video.

Extortionists can also work from available images or video of a child to create deepfaked media that can be used to blackmail them.

The old internet joke, “On the web, nobody knows you are a dog,” has returned, biting viciously.

That gorgeous, soft-spoken Swedish girl who admires your boy-child might a retired Nigerian prince looking for a new revenue stream.

Bissessar is clear about what needs to be done.

“When somebody reports an incident like this, they need to be comfortable about turning over a device with [private] messages between a victim and a perpetrator. It can’t just sit in a drawer in someone’s office. You want to know that the device will be handled properly.”

“That the incident will be escalated to social media companies to gain access to accounts to see if there’s a pattern where this victim was being targeted by a known threat actor.”

“It doesn’t seem that when these incidents take place and schools become aware of it that there’s a formal mechanism to report these incidents or formal tracking of them. They don’t seem to get rolled into statistics.”

“Every [cyberextortion] incident won’t end in suicide, but when bullying or extortion takes place, are we capturing that information? The school system is a good point to begin, because they seem to be aware of what’s happening.”

Reporting of cyberextortion is poor throughout the Caribbean and Latin America, though transparency.org reports that one in five people in the region has experienced sextortion.

There is no statistical breakout of the crime in its internet incarnation. TT has an opportunity here to identify the crime and provide insight into its prevalence in this country by tapping into reports made to the Education Ministry.

Anyone who needs help or thinks about harming themselves can call Lifeline (24-hour hotline) at 800-5588, 866- 5433 or 220-3636.

In case of an emergency (attempted suicide), call 990, 811 or 999.