Above: Image by kikkerdirk/DepositPhotos.

BitDepth#1377 for October 24, 2022

At the third sitting of the Senate on October 13, the Minister of Public Administration, Allyson West, commented on the budget and responded to calls for a work-from-home policy for public servants.

In that speech, the minister made several assertions, some of which are sensible, while others skip over difficult facts that don’t lend themselves to bold, sweeping statements.

West is correct to note, though, that a WFH policy doesn’t start here and today, it has to roll back to the very foundation of public service operations.

A properly functioning public service receives directives from ministers. These policies can be influenced and guided by public servants, chiefly by Permanent Secretaries, but Cabinet has the final say on policy.

Public servants carry out Cabinet’s policy, reporting to the Permanent Secretary, who discusses policy execution with the line minister.

In her Senate contribution, West suggests the government has limited control over the public service, but that’s not true.

The constitution of the Trinidad and Tobago, both as established in 1962 and in the 1976 version, states under section 85, part one, “Where any Minister has been assigned responsibility for any department of government, he shall exercise general direction and control over that department; and, subject to such direction and control, the department shall be under the supervision of a Permanent Secretary whose office shall be a public office.”

Key to understanding how this sentence affects the operations of the public service is the minister’s authority of “general direction and control” and that of the permanent secretary, who is relegated to “supervision.”

The constitution doesn’t assign managerial responsibility to anyone regarding the public service, and efforts to have the role of the permanent secretary changed from supervision to management have been ignored for decades.

Why? Because there is the risk of stiffening the backbone of the cadre of permanent secretaries and thereby limiting the control exercised by ministers, which has sometimes drifted into micromanagement.

What happens when permanent secretaries try to run the public service the way it was conceived to function?

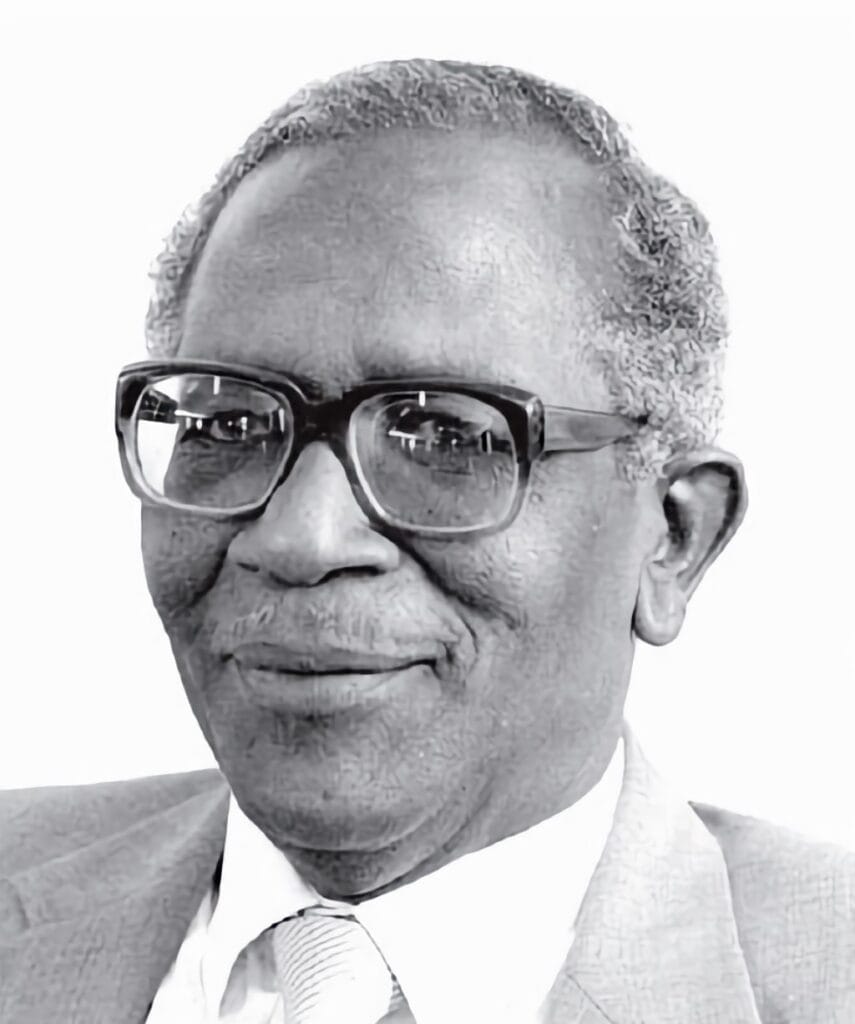

In 1975, Prime Minister Eric Williams launched a rhetorical broadside against an effort by Doddridge Alleyne, Frank Rampersad and Eugenio Moore to build what he saw as a robust public service of qualified technocrats.

These were the leading permanent secretaries of their day and the public rebuff led to a general retreat from leadership initiatives among permanent secretaries that continues to this day.

It was here that the death knell of professional meritocracy and the public service as home to the qualified young professional was sounded.

So the minister can comfortably announce that, “There is no position called Head of the Public Service,” without challenge, while promising rather ominously to “address these anomalies.”

Since 1962, the Permanent Secretary in the Office of the Prime Minister was held to be the Head of the Public Service and appointments acknowledged the seniority of the role.

No recent permanent secretary in that role has acted in that capacity or operated with that implied authority, so the role has degraded to the point that West appears confident that she can neuter it entirely.

That would only further deteriorate the authorities of Permanent Secretaries, whose relationship with ministers she describes as an “artificial, illogical reality.”

In that she’s correct, but doesn’t mention that the situation is a political invention, not a circumstance of the intended architecture of the system.

The minister promises the reactivation of the National Strategic Human Resource Management Council, a coalition of the Public Administration Ministry, the Personnel Department and the Service Commissions.

The council was originally convened by the People’s Partnership government and dissolved by the incoming PNM administration in 2015.

As a planning body, it notably does not include stakeholders from the working public service or the unions representing them.

The reactivated National Strategic Human Resource Management Council notably does not include stakeholders from the working public service or the unions representing them.

It’s not the first effort at addressing the issues of the public service.

The Public Service Reform Task Force collapsed in 1990 in the wake of the coup attempt.

Gordon Draper worked to reconsider the public service as a human resource between 1991 and 1995, but that effort ended with the incoming UNC government.

It’s easy enough to talk about modernising the public service.

A 2017 public service workshop suggested the creation of a “central HR agency separate from Ministries with an independent organization to provide oversight.” That idea lived and died at the event.

The report of a committee convened by Cabinet recommended, in 2017, the creation of the post of Permanent Secretary to the Prime Minister and Head of the Public Service.

Nothing will happen, not WFH, not improved customer service, until the government accepts its role as much as it expects the public service to.

The government’s bristling over work from home isn’t really about technology or even performance. It’s about what is really necessary to transform the public service, to rationalise its workforce and to create a culture of functional accountability and delivery.

The public service’s spotty adoption of IHRIS, its digital human resource management tool, isn’t only the result of a lack of public servant’s enthusiasm.

Pervasive use of IHRIS, for instance would reveal the reality of the public service, which is much smaller than we think, uncovering all the vacancies that are not for real jobs and go unfunded in budget after budget for political reasons.

This is not a job for the Public Administration Ministry, even if West seems to think that it is.

It is a collective project for the Cabinet, which must undo the hobbling tangle of responsibilities that date back to this country’s first independent constitution.

And it must do so in consultation with public servants, civil society and the private sector.