- The consumer technology sector promotes consumption as a way of life, leading to the rapid obsolescence of functional hardware

- Many older Intel Macs will become unusable due to hardware failures or lack of affordable repair options

- OpenCore offers a reversible process for upgrading to unsupported OS versions

Above: The OpenCore app icon. Images courtesy Dortania.

BitDepth 1541 for December 15, 2025

In 1955, writing in a research essay in the Journal of Retailing (PDF), Victor Lebow summarised the rise of consumerism.

“Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction and our ego satisfaction in consumption. We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced and discarded at an ever-increasing rate.”

The consumer technology sector has embraced that with vigor. While style erodes the wearability of clothing, conflicting technology standards, advances in software and general hipness have accelerated the demise of otherwise functional hardware, consigning the workable to the dump.

It’s estimated that between 2006 and 2023, Apple manufactured more than 300 million Macintosh computers that ran on Intel chips.

That line ended with the overpriced and underwhelming 2019 MacPro, which was replaced in 2023 with an equally pointless M series version in 2023.

There’s a clock running on software support for Macs Apple stops selling, particularly when the company changes its entire chip architecture, which it did twice before it began designing its own Apple Silicon chips.

The 68000 series Motorola chips were replaced by PowerPC chips in 1994 and were changed from PowerPC to Intel in 2006.

When Intel Macs were introduced in June 2005, it took Apple four years to drop support for the older PowerPC chips.

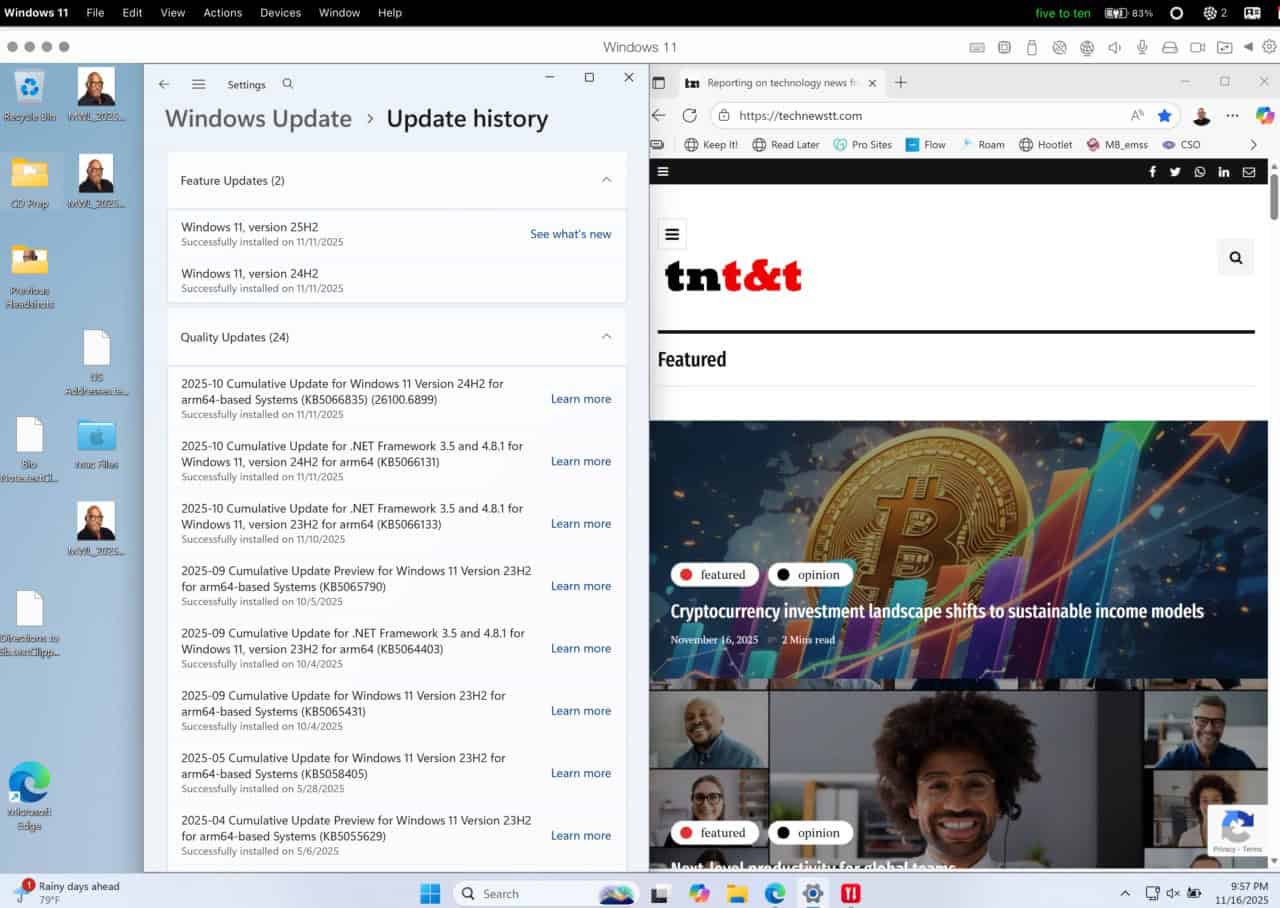

OS26, Tahoe, will be the last to support Intel Macs and very few of them at that.

That will end the era of the hackintosh, built PCs that run a hacked MacOS, as well as the more approachable OpenCore Legacy Patcher (OCLP), a project that’s intended to reverse Apple’s enforced obsolescence.

Many older Intel Macs will experience terminal hardware failures or having been declared obsolete by Apple, can’t be affordably repaired through official channels, but many more will chug along.

But among the millions of Macs abandoned by their OS, one came to my attention, a 2013 iMac that had never been used.

The original plastic packaging wrap had to be peeled off the screen carefully, because age had begun to bind it to the glass of the screen.

The Mac could run MacOS Catalina (10.15) from 2019 but no further.

It has a powerful i7 processor and a graphics card capable of supporting Metal, Apple’s low level code for GPUs. Without that GPU support, a Mac can’t be upgraded beyond High Sierra.

OCLP assesses the Mac’s hardware environment on launch. If the CPU is powerful enough (Intel Core Duos don’t make the cut), has enough RAM (8GB and above strongly recommended) and a Metal capable graphics card, the next steps are pleasantly straightforward.

Earlier versions of OCLP demanded concentration and care, but the current release is almost as easy to use as an official Apple installer.

While it’s best to start with a computer that can be completely erased, OCLP can be installed over an existing system, but backup before proceeding.

The software will first ask for a copy of the target version of MacOS. This part can be complicated, because the MacApp store only makes it easy to get the most recent version of MacOS.

There are several websites that host links that link to older OS releases on the App store from Big Sur (11.7) to Sequoia (15.7).

The software also offers to download a selected OS version itself, but I found that process slower and prone to transfer failures.

OCLP will then create a bootable version of the OS on external media. A 32GB flash drive is recommended, but I used a blank SSD successfully.

On restart, select the external volume and OCLP will then install a version of that OS on the destination computer. It takes less than a half an hour of personal time, but the system spends much longer to get its OS installations sorted.

Expect the whole process to take two to three hours, depending on your internet connection speed.

A successful upgrade requires one more step, the modification of kernel extensions (kexts) that are the bridge between the core OS and external devices such as a keyboard or mouse.

For most users, the best OS versions to target are Sonoma (14.8) and Sequoia, because these systems are still receiving minor security and improvement updates. Unfortunately, every incremental update erases the hacked kexts, but OCLP reliably offers to reapply its alterations.

In practice, there is no significant penalty to going the OCLP route since the process is reversible and your Mac is out of warranty. You can return to an officially supported version again if you wish.

Older OS versions do not receive security updates and eventually get dropped by other software vendors, ending upgrades to software that you may need such as browsers.

An OS that falls far enough behind eventually becomes unusable in subtle but annoying ways.

OCLP doesn’t make the old hardware any faster or more efficient. The overhead of newer OS versions may actually slow things down a bit, but most common computing tasks will generally be improved by a newer version of the MacOS, even one you’re not supposed to have.