- The siloed approach in the Caribbean hinders effective information sharing for coordinated responses to various cyber threats

- The absence of legislation requiring incident disclosure hinders effective response efforts

- Moving beyond seeking scapegoats to foser a culture of trust and responsibility

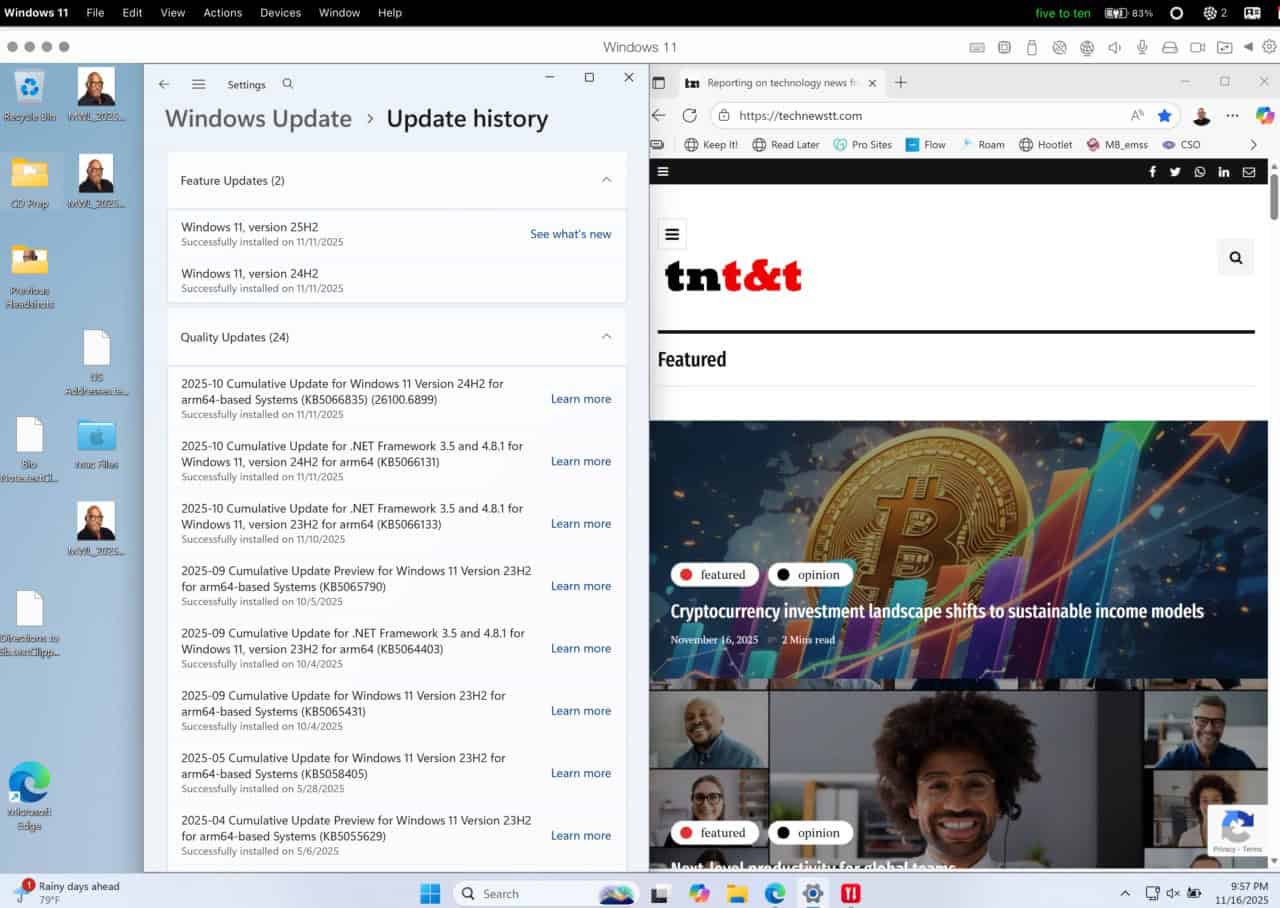

Above: Dale Joseph. Image captured from video footage.

BitDepth 1540 for December 08, 2025

On the first day of the cybersecurity track at AmCham’s Health, Safety, Security, and Environment (HSSE) Conference on November 11, the regional response to cybersecurity threats led the agenda.

The discussion on the topic Outpaced and under fire – Navigating the new era of cyber threats, was summarised by moderator Gerardo Rivera Menjivar, “Traditional threat models are being outpaced and this means, our strategies, governance, culture must evolve just as fast.”

Even casual observers of cybersecurity breaches are aware that attacks on businesses have increased dramatically over the last six years, despite industrious local efforts to keep successful breaches a business secret.

Some cyber attacks were so bold and their impact so disruptive that they couldn’t be hidden. How does TT and the region move forward from an approach that clearly isn’t working?

“We still operate largely in silos in the Caribbean,” said Dale Joseph, Chief Analyst, Cyber, at CARICOM IMPACS, the region’s collective implementation agency for crime and security response.

“That’s a problem, because if we don’t share information, we won’t be able to coordinate and we won’t be able to respond to [threats effectively]. It could be ransomware, it could be AI-enabled threats, but if we don’t share information, we won’t be able to coordinate and have a structured, realistic response.”

“In response to a cyber incident, there’s often confusion, knowing who to call, when to call, and who has responsibilities for what. That’s a challenge for us.”

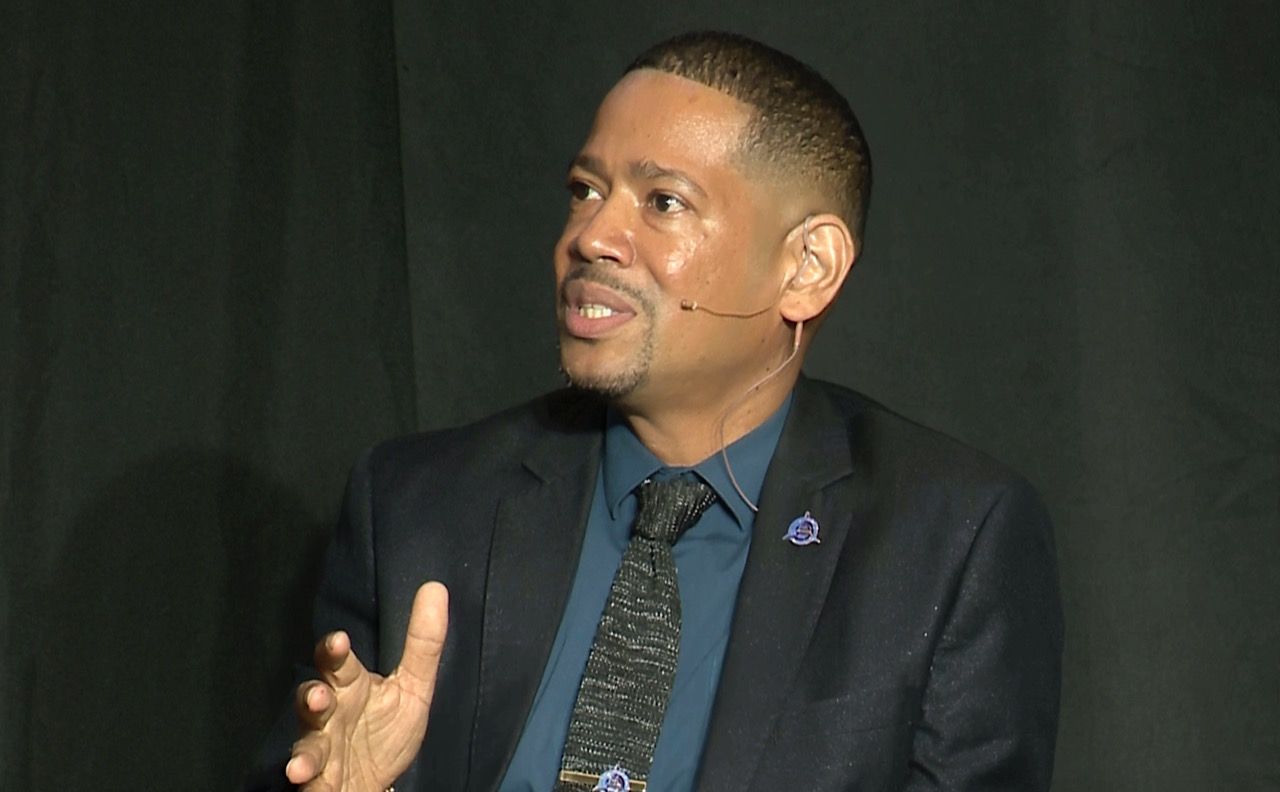

“Just having asset management, even an Excel sheet [listing] some of your main assets, I’ll take that as opposed to nothing,” said Anish Bachu Head of the National Cyber Security Incident Response Team (TT-CSIRT).

“That’s where things fall apart through failure to prepare. I can’t tell you how many times, during an incident, we’re trying to figure these things out on the fly.”

“You never want, on one of the worst days of your professional career, in the company’s operations, to be trying to figure out who to call. I think the biggest failure [I’ve experienced] is the failure to prepare.”

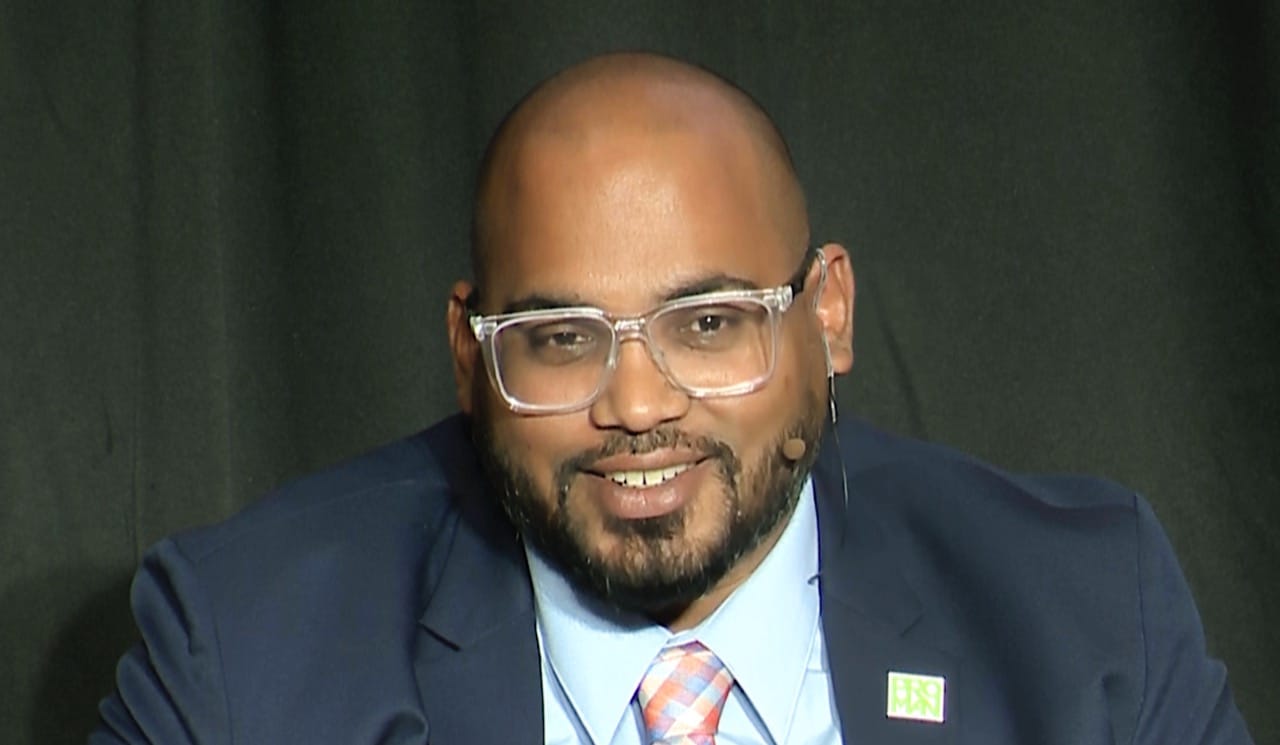

“From an organizational standpoint a siloed approach is one of the biggest hindrances to resilience,” agreed Travais Sookoo, Security Engineer with Check Point, a cybersecurity response and risk assessment company.

“Every department, is juggling and running to do something, but nobody’s coordinating in-between. [In my] experience across the region, that lack of coordination during an event leads to slower recovery, and after an event, a lack of lessons learned to improve handling of future incidents.”

The lack of legislation requiring disclosure from businesses or government agencies after a breach is another stumbling block to effective response.

“If you don’t tell the doctor your symptoms, you can’t be treated,” Joseph said.

“In Trinidad and Tobago and many other islands in the Caribbean, there’s still no legislation to compel organizations to report incidents. I’ll get a call from other contacts, there’s an incident.”

“But is there a structured approach for them in legislation that would compel them to report? Preparedness and coordination would dovetail from that approach. This structure would come from a national security strategy.”

Should leaders be held personally accountable for inaction that leads to cybersecurity risks?

“We’re all accountable for something. If I’m not accountable from a business perspective, then who really drives this change? No one,” said Terrence Panchoo, head of technology at Proman Trinidad.

“If I’m unable to say, yes, this is a result of an issue that we had, then who really is responsible? There’s a move to legal accountability for corporate executives. In the event of gross negligence, they will be held accountable and are potentially liable, whether it be in financial compensation or other mechanisms.”

“Boards that are being formed now accept that these areas of both cybersecurity and ECG (Ethics, Compliance and Governance) are critical components [of their scope of responsibilities].”

“[When it comes to] accountability in failures in cybersecurity, it needs to be a balanced discussion,” said Bachu.

“Looking for a head to put on the block at the onset of a cyber incident will not get us anywhere productive. I only get information [from the C-suite] if they see me as a trusted source.”

“If they see me as somebody that they could talk to without getting in trouble with their board or without getting in trouble with their line minister. If I share this information with you, I’m going to get in trouble.”

“We’re still talking about getting boards to accept that responsibility, getting senior persons in government to accept that responsibility. Once we get to the point where somebody owns it, then we can talk about accountability after the fact.”

“Many organizations treat compliance as resilience, but compliance should be the floor, the base,” said Sookoo.

“We do compliance to comply with regulations, meet the requirements and continue business. But if compliance is the floor, resilience should be the ceiling. All of us here should know our cost for downtime.”

“In 2018, Amazon said their cost for one minute of downtime is a million. Do executives ask themselves what is the cost of their organisation’s downtime?”

“Quantifying that cost also [offers an] opportunity to incentivize not only a board, but your entire company, [making it] a metric to achieve,” said Panchoo.

“It’s an opportunity to move from just compliance to more of a [business] positioning.”

“The CARICOM Cybersecurity and Cybercrime Action Plan (CCSCAP) is a structured approach to cyber resilience at a regional level.” said Joseph.

“The plan has awareness and advocacy as one of the priority areas, capacity building and development, enhancing technical standards and infrastructure, policy, institutional, regulatory frameworks, cyber incident management, and regional and international cooperation.”

“As the Caricom member in charge of security and energy, TT should be taking the lead in adopting that plan, ensuring its implementation in government and in our governance partnerships with the private sector,” Bachu said.

IMPACS has been doing its part to raise awareness regionally and since 2019 has engaged in awareness building in the region among all 15 member states emphasising the importance of cybersecurity resilience.

In Trinidad and Tobago, IMPACS has done sensitisation sessions with high-level governmental officials, key operational stakeholders and members of the public.

“Strategic documents for business continuity have to be living documents,” said Joseph. “What’s required over the next five years is a commitment to reworking partnerships, agile leadership and decision-making, legislation, strategy and policy with an emphasis on agility.”