- Apple introduced DOS compatibility cards on early

- Early software emulation was slow

- Users who needed Windows-exclusive applications or wanted to test code in different environments could utilize these solutions.

- Wine translates Windows API calls into POSIX calls, allowing Windows software to run on Unix and Linux

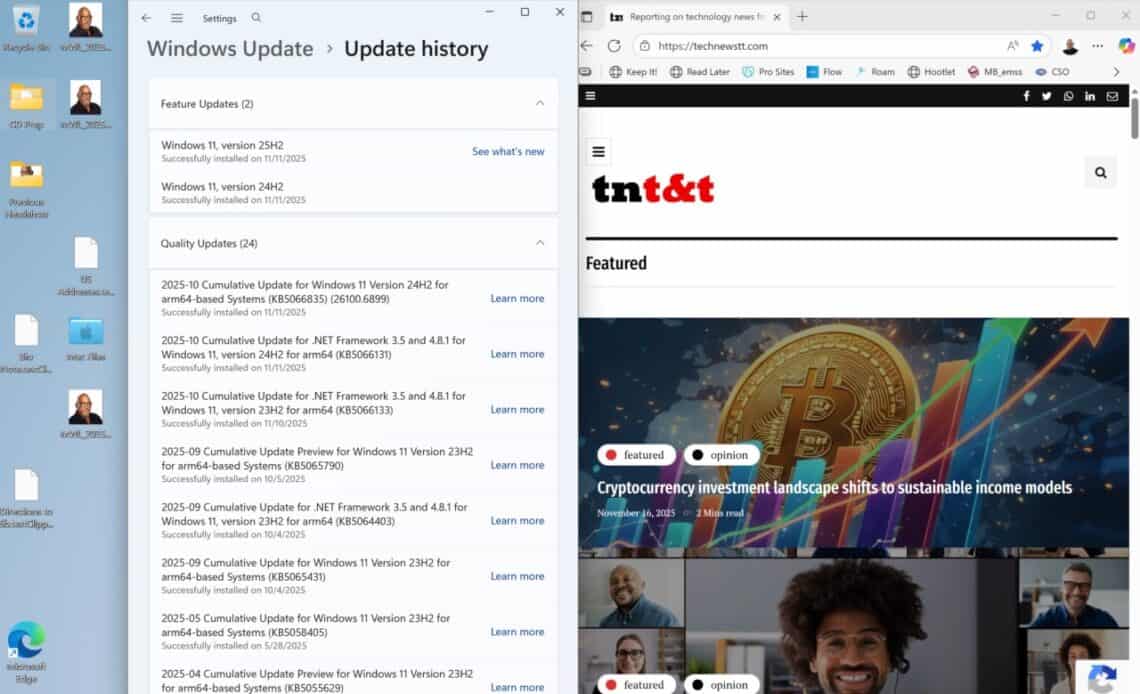

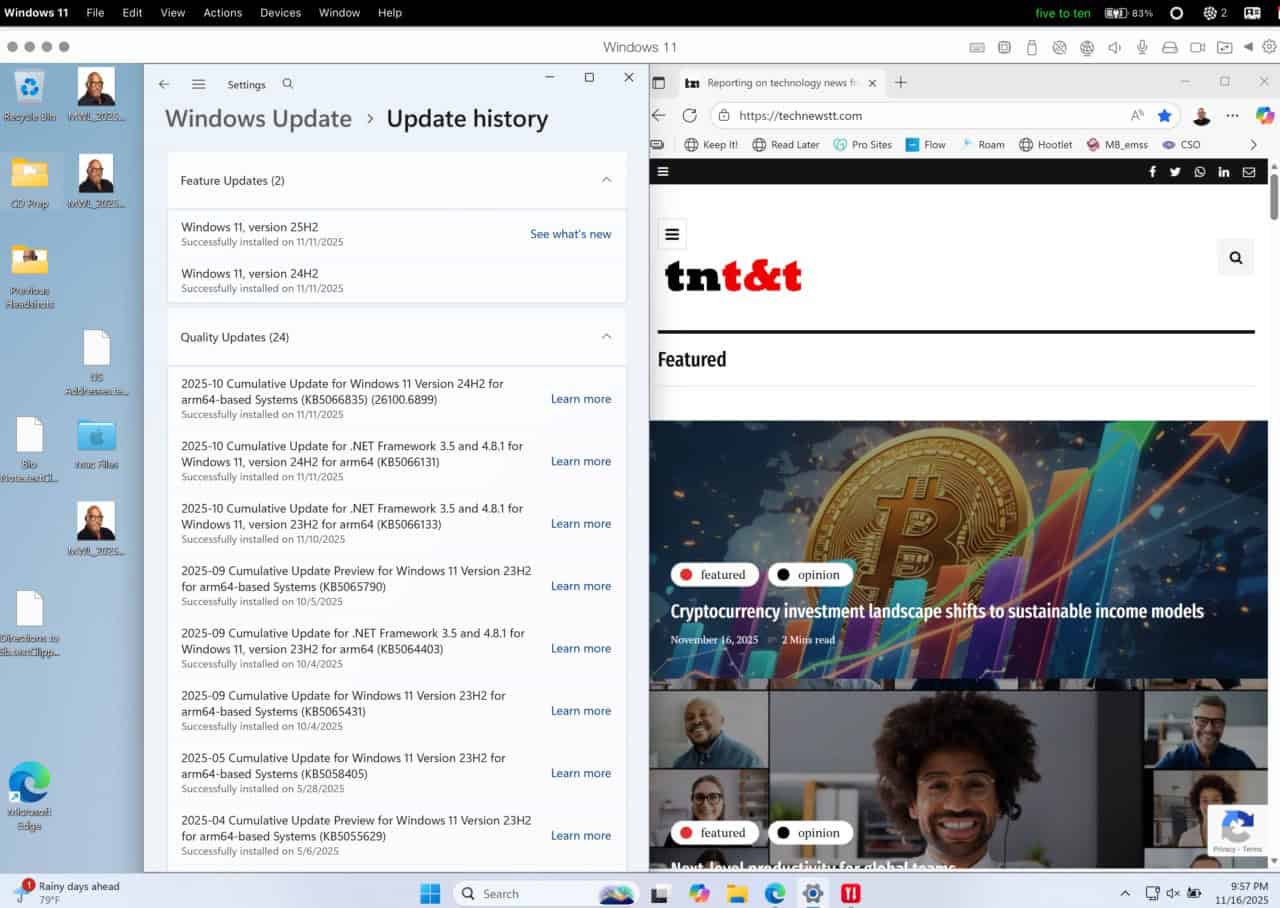

Above: Windows for ARM processors updating in Parallels Desktop.

BitDepth 1536 for November 17, 2025

There are a lot fewer reasons to want to run Windows on a Mac these days than there used to be.

My adventures with running Microsoft’s OS on a Macintosh began with a copy of Soft Windows around 1993. Apple’s computers ran Motorola’s 68040 chips back then, and performance in virtualisation was barely functional.

As a solution, Apple first introduced a 25MHZ 486 DOS compatibility card that you added to a Quadra 610’s processor direct slot.

There was at least one card made for the Nubus slot, a predecessor to PCI on those early systems.

There are active forums where dedicated users are still trying to get these cards working on legacy Macs.

Many high end 68000 series had this slot and they would become useful after the computers were switched to the PowerPC chip. I’d upgrade an old IIci with a PowerPC card in that PDS slot and run it for a couple of years.

The PowerPC chip, significantly more powerful than the old Motorola chips made Connectix Virtual PC, which arrived in 1997, a more palatable proposition.

Software virtualisation solutions were a great solution for users who just needed to run one or two apps on Windows that weren’t processor intensive.

Microsoft Access, for instance, was never released for the Mac, so if you needed to use it, this was one way to do all the work on a single computer system.

Why do that?

Developers can use multiple virtual environments to test code in a virtual sandbox. Gamers can run an app that isn’t resource intensive.

As processors improved, so too did the effectiveness of virtualisation, but after Apple switched to Intel processors, they offered another option, Boot Camp, which allowed users to double boot a single computer as either a Windows or a Mac system.

The big upside was that the software ran at the native speed of the Intel processor, but while the two systems coexisted, they weren’t connected. You were either running Windows or MacOS.

Boot Camp still works on existing Intel Macs, but can’t run Windows 11, which requires hardware the Mac doesn’t have.

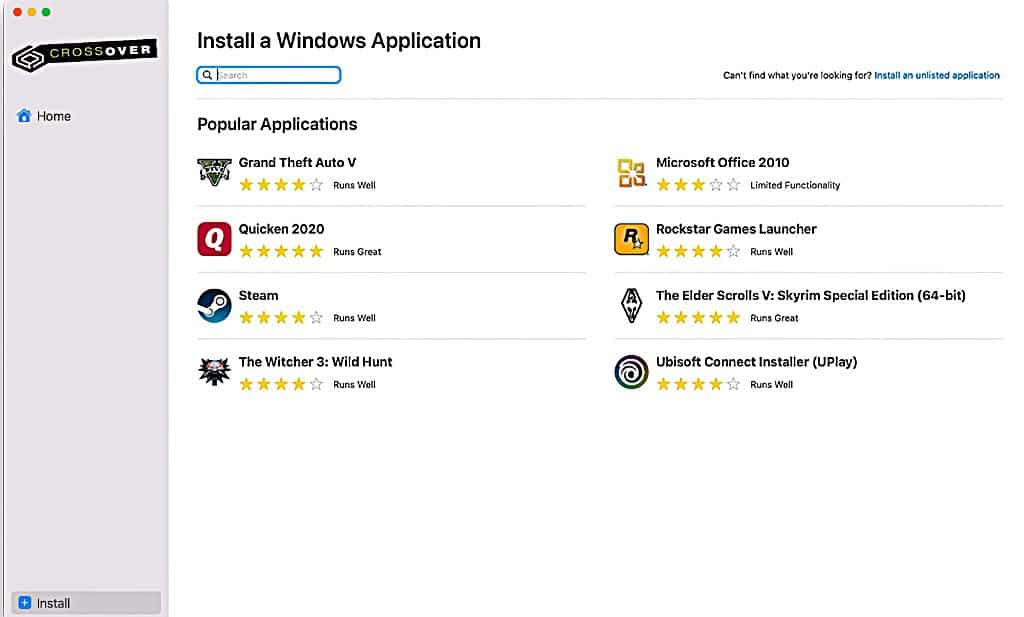

Between double-booting and virtualisation lies another solution, the compatibility layer offered by Wine (Wine is Not an Emulator), the software that underpins tools like Apple’s new Game Porting Kit (GPKT), the recently discontinued Whisky and the popular CrossOver app.

Wine doesn’t support every Windows app, nor does it require a license for Windows itself. It was originally developed in 1993 to allow Unix and Linux users to run Windows software on their workstations.

According to the software’s developers, “Wine translates Windows API calls into POSIX calls on-the-fly, eliminating the performance and memory penalties of other methods.”

Wine offers an option for Windows compatibility without an actual installation of Windows, but the most elegant and straightforward way to use Windows or Linux on a Mac has always been virtualisation.

Oddly, Apple makes it difficult to the point of near impossibility to virtualise earlier versions of its operating system.

Since the days of Soft Windows and Virtual PC, virtualisation has been refined to the point where it isn’t even necessary to see the Windows desktop. Parallels Desktop features coherence mode, which hides the desktop while launching the required app. The entire environment is up and running, but hidden from the user.

I run Windows in its own space, usually parked over on a secondary screen, but that’s because I use virtualisation as a test bed for software and services that require Microsoft’s OS.

Coherence makes better sense for users who need to run one or two Windows apps as part of their workflow.

Anyone looking for an option to run modern, PC-only games on a Mac is better served by the online service Steam, which makes clear which games are Mac native and which run on CrossOver. The company recently introduced a version of the app for Linux.

CrossOver now includes the improvements that GPKT introduced, including a DirectX to Metal translation layer.

Using cloud-based virtualisation, you can rent a Windows365 server instance that will run on any platform, including your phone, but at enterprise pricing.

NVidia’s GeForce Now offers 4,000 games that are streamed from its servers to any platform.

Parallels Desktop is the easiest option for virtualising Windows or Linux on the Mac in 2025. But it’s not cheap and functions on a subscription model, not my favorite way of working with software.

You’ll need the newest version of Parallels to virtualise on a modern Mac though, because older versions don’t work on the M-series chips.

Other options, like VMWare Fusion (commitment to end-user virtualization is shaky), Oracle’s open source VirtualBox and UTM are either cheap or free, but the user pays the price in preparing the virtual environment. I simply couldn’t get Windows running in UTM, and I found VMWare to be shaky last year.

Your mileage will certainly vary, particularly if you are willing to spend time on it or are comfortable with technology challenges.

I managed to get a couple of Linux distros running on UTM without problems though, so the issue is definitely more me than the software.

Parallels supports Windows 11 Pro for ARM processors and I wanted to follow the development of the OS, the first “new” version of Windows for the desktop since NT, and more specifically, how it maintains compatibility with older software.

Using virtualisation, I’ve run everything from Windows 3.1 to Windows Pro 11. The best of the lot? Windows 2000 without question.

[…] Caribbean – There are a lot fewer reasons to want to run Windows on a Mac these days than there used to be… more […]