- Encryption is crucial for protecting digital privacy and securing sensitive information in our increasingly digital lives

- Weakening encryption for public safety can create vulnerabilities and lead to misuse

- Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), introduced in 1991, was one of the first public implementations of asymmetric encryption

Above: Illustration by aureilaki/DepositPhotos

BitDepth 1534 for October 27, 2025

Encryption is a key pillar of digital society, occupying a delicate space between privacy and public safety.

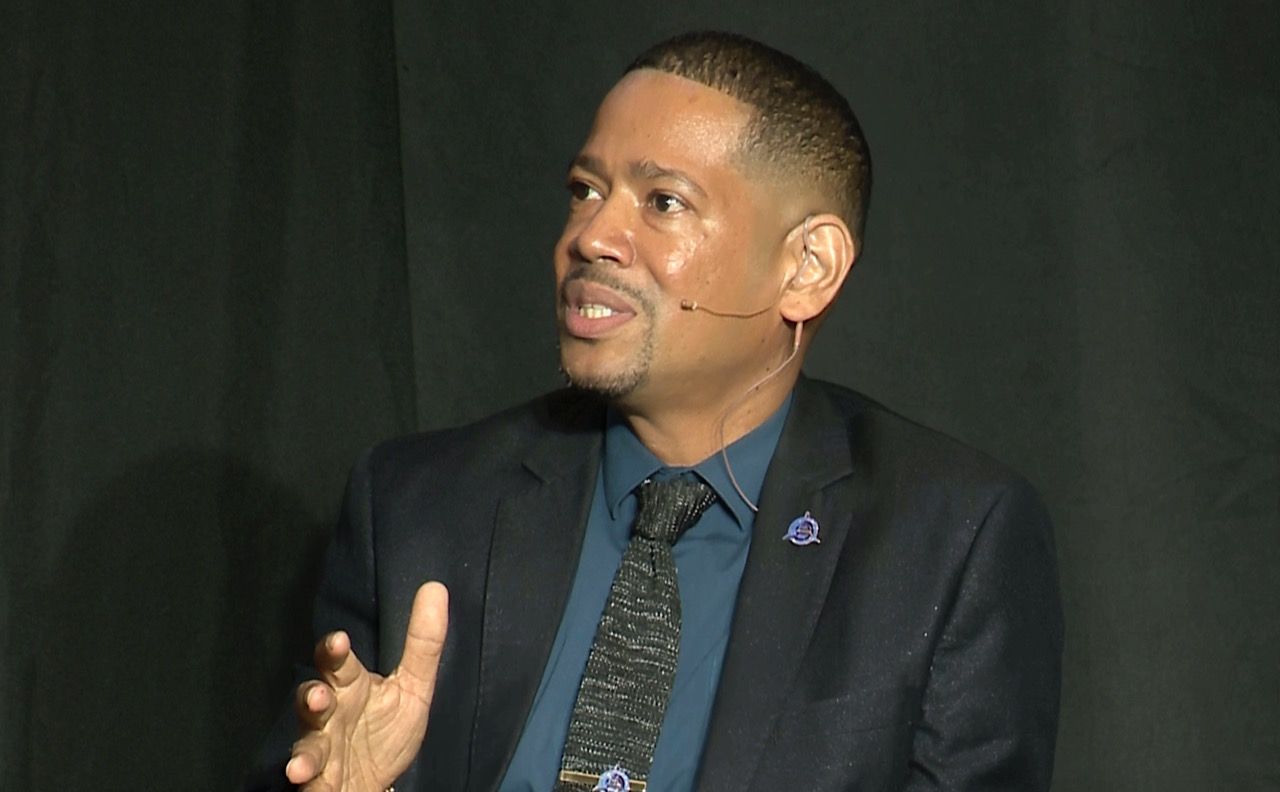

October 21 was Global Encryption Day and the TT Internet Society (ISOCTT), the CTU, the TT Computer Society and the local chapter of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) partnered to host a webinar discussion on the importance of this aspect of technology.

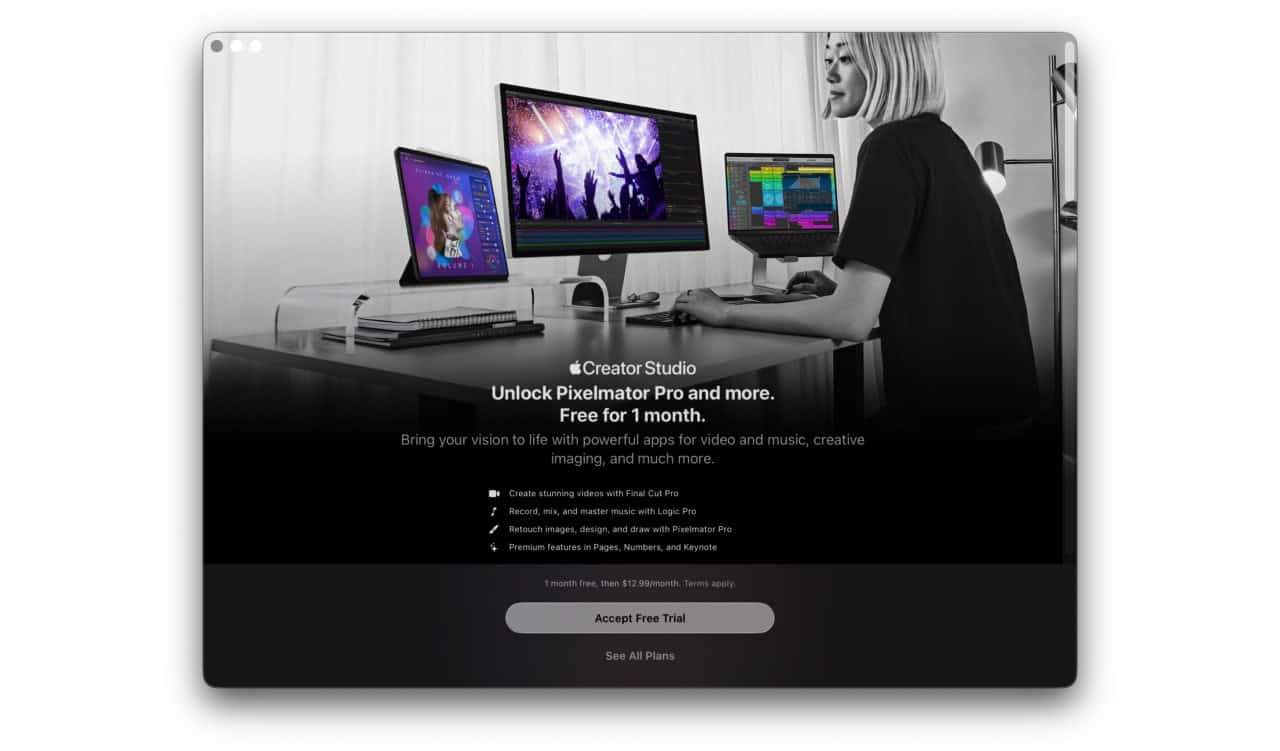

Introducing the presentation, moderator Kevon Swift, chairman of ISOCTT noted that, “Encryption day may sound like something for the tech savvy, but in truth it’s about all of us. Encryption is what keeps our messages private, our bank transactions secure and our digital lives, from health records to voice notes, protected from prying eyes”.

“In a world where nearly everything we do leaves a digital trace, encryption is less of an option and more of a civic safeguard. Around the world, governments are grappling with how to balance privacy with public safety.”

“Globally, proposals to weaken encryption through back doors or exceptional access tend to open much larger doors. Doors that invite misuse.”

Sachin Ganpat, secretary of the TT chapter of the IEEE, offered an explanation of how encryption works.

“You send messages. You send files. You shop. You bank. Each one of those actions transmits personal information,” Ganpat said.

“Without encryption, that data can be read, copied or changed in transit. Encryption makes that data unreadable to outsiders. That’s sealing a letter that only the right person can open.”

“What does encryption look like in everyday life? We see it in WhatsApp. We see it when you browse websites secured using HTTPS. That S stands for secure. The latest Wi-Fi uses WPA3 AES256 encryption, the strongest encryption that we have to secure our connections to the access point. Many laptops and computers have that available today by default.”

Widespread use of hardware and transmission encryption was facilitated by the increasing speed of computer chips and solid state disk access.

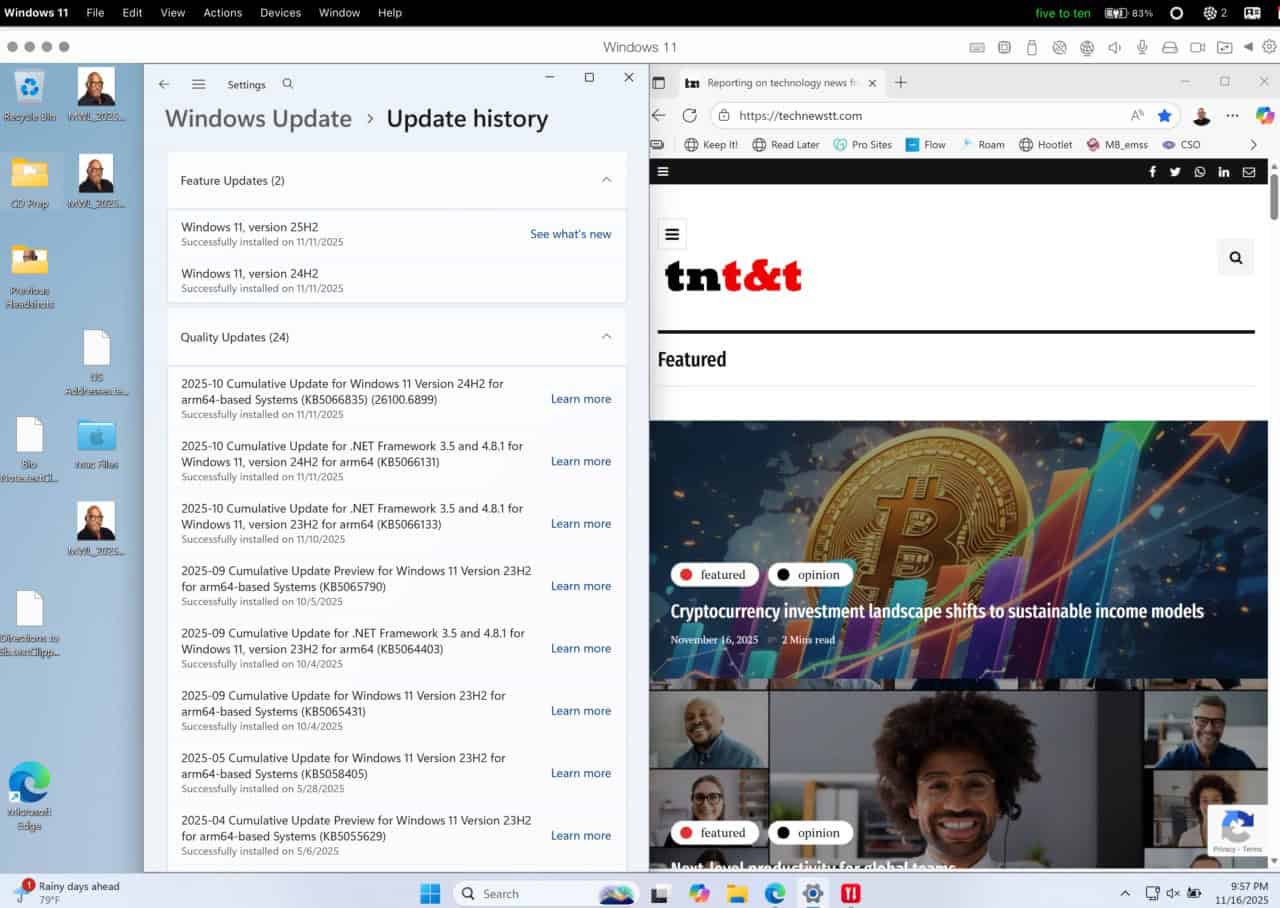

MacOS using FileVault and Windows using BitLocker encrypt and decrypt data stored on a drive in real time without the perceptual overhead that limited widespread use of disk encryption on earlier devices.

Ganpat explained that there are two primary models for encryption, symmetric and asymmetric.

“In symmetric encryption, the plain text is run through an encryption key. That encryption algorithm requires the key to decrypt the plain text. In asymmetric encryption, the user and the algorithm produce two keys.”

“One key is known as a public key and the other, a private key. Someone sending you a file or data will use your public key to encrypt it. Then you use your private key to decrypt it. If you’re sending the file back to the person, you will use that person’s public key to encrypt the file, and they will use their private key to decrypt it.”

One of the earliest public implementations of asymmetrical encryption was Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) introduced in 1991. PGP initially faltered because it required users to master its learning curve. Early vulnerabilities limited its adoption by the technology savvy.

Later versions of PGP proved robust enough to frustrate law enforcement. As recently as 2007, police investigators could not open files secured with it.

Given enough time and resources, Ganpat noted, any encryption can be broken, and modern computers are capable of reducing that time dramatically, though not as speedily as quantum computers are expected to.

While there is no functioning quantum computer available to the public, as recently as last week, Google announced that it had successfully run an algorithm on a quantum chip 13,000 times faster than on existing chipsets.

Some systems secured by encryption are being advertised as being “ready” for such code cracking power, but practical challenges are still years away.

The other test that encryption faces is legal, as governments argue that being able to access encrypted data through digital backdoors is in the public interest.

This is an issue that Dr Raquel Gallo, a general counsel and head of legal at Brazil’s Network Information Center (NIC) has been considering.

“Often this effort is a false dichotomy between privacy and security, between encryption being a way to hide things and to protect criminals instead of saying this is a protection for us all,” Gallo said.

“These are legitimate concerns [by nation states] that they have to protect citizens, but there is a lack of awareness of the effects it might have. One example is luggage locks. These were very common in Brazil, but when you travel to US, you need to use one that is TSA approved with a key that only customs can open to check your luggage. Do you believe only customs can have this key?”

Brazil is in its ninth year of considering the consequences of government mandated access to encrypted messages in WhatsApp, having banned the app entirely temporarily in 2016.

Rishi Maharaj, managing director of Privicy Advisory Services, pointed out that such concerns are largely theoretical in Trinidad and Tobago leaving the country dramatically out of step with evolving standards in the EU and the wider Caribbean.

“The Data Protection Act of 2011 has never been fully implemented and is limited mainly to the public sector, leaving private organizations largely outside its regulatory scope,” Maharaj said.

“The absence of a comprehensive, enforceable regime means citizens lack meaningful rights over their personal data, while organizations operate without clear obligations or oversight. This gap carries real consequences.”

“The recent TSTT data breach exposed not only the vulnerabilities in cybersecurity but also the deeper issue of accountability. Individuals affected had no legal avenue to demand transparency, compensation, or corrective action. If Trinidad and Tobago is serious about building a digital society, it must first build a legal framework that protects those who participate in it.”

“Unchecked data collection and unregulated surveillance also threaten freedom and democracy. When individuals know they are being monitored, they self-censor. Journalists and activists are particularly vulnerable to state or corporate surveillance justified under “security” concerns. When data is weaponized, trust collapses, and civic participation declines— eroding the democratic fabric of our societies.”

[…] Trinidad and Tobago – Encryption is a key pillar of digital society, occupying a delicate space between privacy and public safety… more […]