- The Barbados government will acquire the archives of Banyan, a television documentary company.

- The archive preserves not just final products but also source material, offering a comprehensive view of creative work.

- Carnival’s organizers and stakeholders fail to preserve the festival’s creative output, leading to the loss of valuable cultural assets.

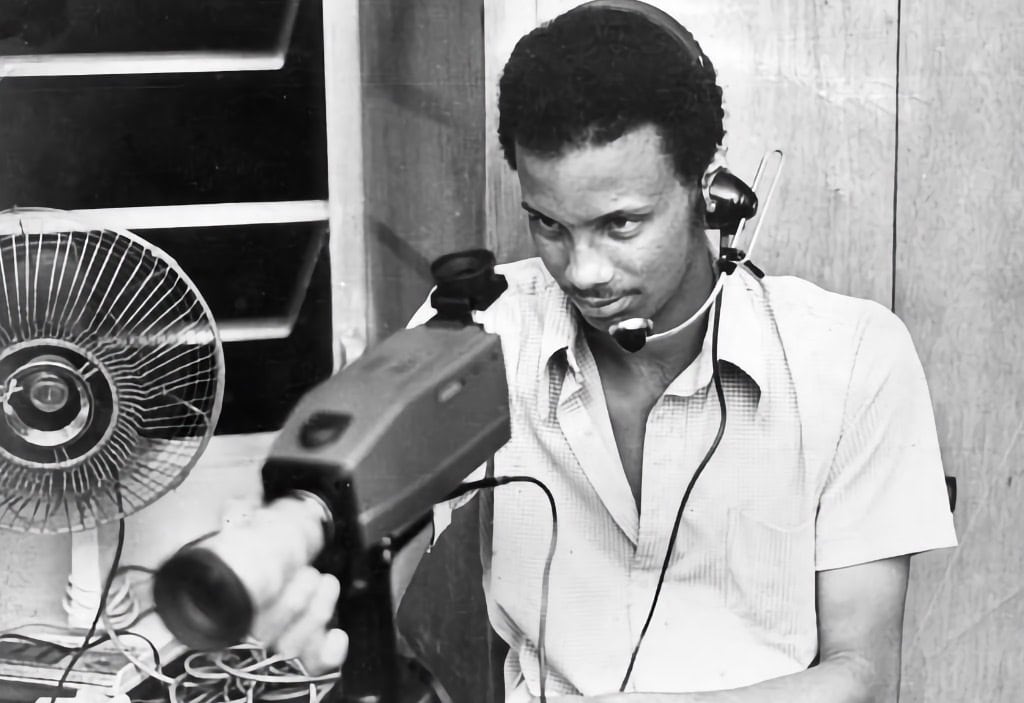

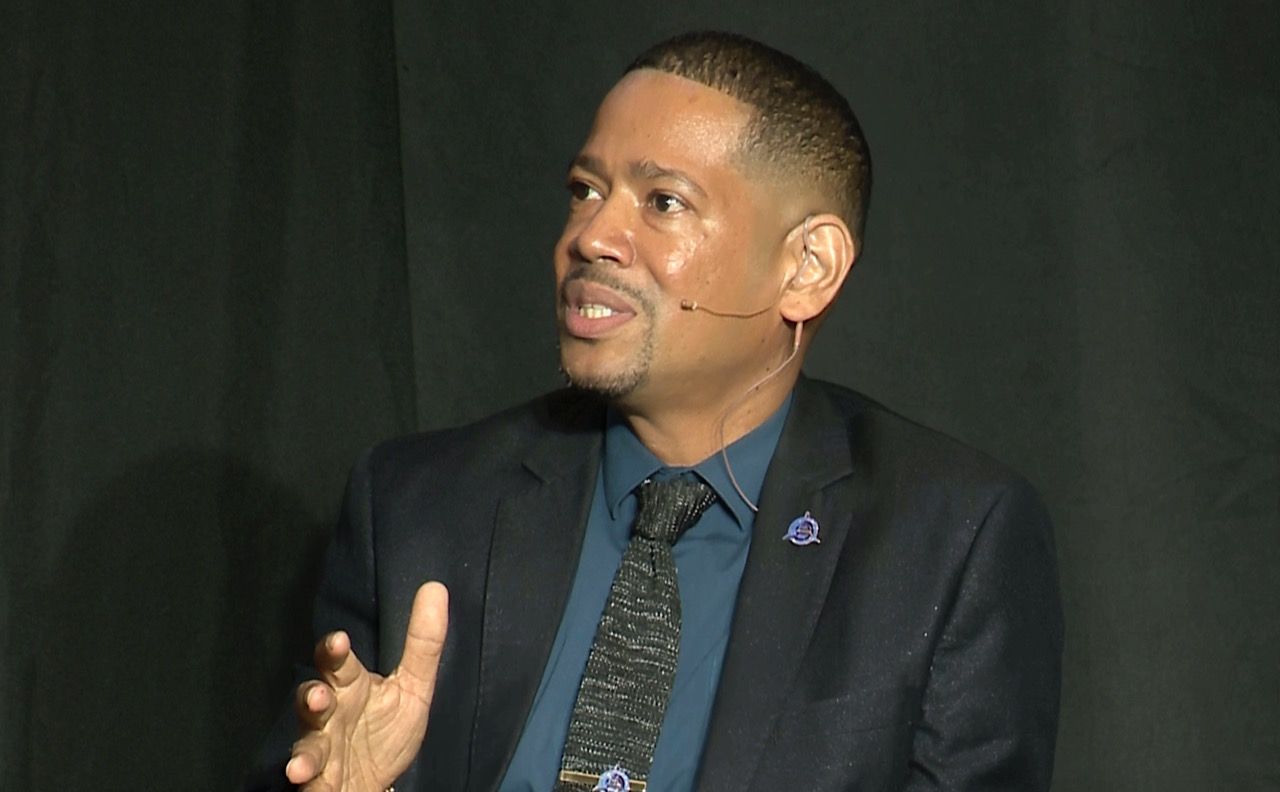

Above: Christopher Laird, photographed in 2005. Photo by Mark Lyndersay

BitDepth#1527 for September 08, 2025

On August 22, at the opening of Carifesta, Prime Minister Mia Mottley announced that the Barbados government would acquire the archives of Banyan, a television documentary company focused on local cultural content over the last 50 years.

The announcement came almost three years after the late Mark Loquan announced that NGC would acquire the archive.

The institutionally cavalier treatment of TT’s history as recorded by its journalists is a topic that I’ve returned to often in this column, most directly in a 2017 column.

Decades ago at a TT talk shop, a person I remember as former PoS Mayor John Rahael pointing out that the key difference between the rich and the middle-class wasn’t just how much money they earned, it was how much they kept, underlining the difference between assets and expenses.

Great wealth did not visit me because of his advice, but his counsel did not fall on deaf ears.

Dovetailing it with decades spent observing the great care that the late photographer Noel Norton took of his negatives, I recommitted to preserving my only real assets, my photographs and writing.

Choosing that path is hard enough. Actually walking it is painfully difficult. Guarding creative work against the predations of IP thieves, predatory work for hire agreements and the inexperience of solo freelancing dented those efforts over the years.

My work as a photographer actually began with video, controlling an early video camera for the pilot Family Planning Association video that would become Who The CAP fits, a seminal Banyan education series that mixed creole narrative with life counsel.

The musician Ronald Reid brought me first to a backyard meeting at the Woodbrook home of Maurice Brash where the early Banyan was brainstorming a Christmas special for broadcast on TTT.

Looking back at the talent in that room, Christopher and Judith Laird, Maurice Brash, Bruce Paddington, Dawud Orr, Ron and Christopher Pinheiro, I wasn’t only out of my depth; I was generously buoyed by their collective patience and support.

That first self-produced pilot, starring Joanne Kilgour and John Isaacs was recorded on reel to reel magnetic tape hard-wired to cameras under the supervision of a UN consultant. It is also a part of the Banyan archive.

Video has always been a collaborative, human resource intensive endeavor, and the experience pushed me to still photography, which I could pursue on my own, but Banyan never let me go, something I never forgot.

Laird would ask me to contribute music reviews for his cultural magazine, Kairi, and again when the call came to review theatrical productions on my motorbike for early episodes of Gayelle. Four episodes into that experience, people began recognizing me in the street and I quickly retired the slot.

More recently, after Gayelle the Channel began broadcasting quite literally around the corner from my studio, I volunteered to do promotional photos of the hosts of its shows.

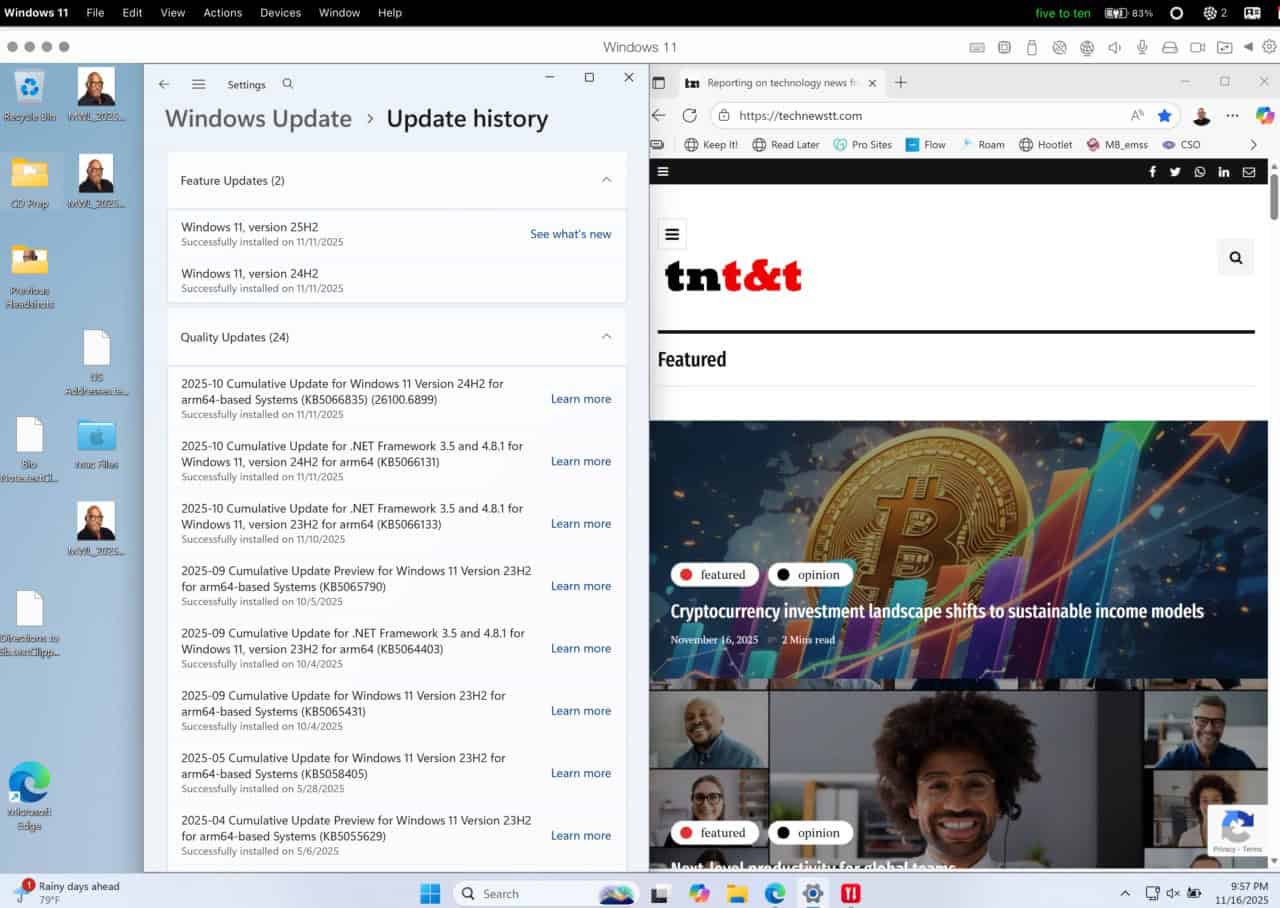

My continued intersections with Banyan offered a unique window into Laird’s fight to first maintain archives of the station’s output, then to digitize Banyan’s archive of tapes.

His industry is remarkable. A roll of film in an archival file sheet with a contact print fits into a standard manila envelope easily.

Early video tape captured short clips and even the industry standard U-Matic tape, half the size of a cereal box, held between 30 to 60 minutes worth of raw footage. A simple two-camera setup resulted in a shoe-box full of tape cartridges.

Chris Laird didn’t just hold onto the edited work, he managed to preserve the raw footage of critical interviews and conversations, an unprecedented record of evolving regional talent that covers a half-century of creative work in TT and the wider Caribbean.

In assembling an archive like this, it’s possible to identify some gems early, but history often redefines overlooked heroes in retrospect, and both the mundane and the outrageous look quite different decades later.

Standing between a potential library and the city dump is often the work of a single person determined to ignore the national inclination to dispose of creative work. “If yuh so good, just make more nah.”

The work I produced as an employee hired to make photographs covers just five years out of the last 49 but my inquiries into specific work in this decade revealed that all of it is now completely destroyed.

In 1993, just three years after photographing the attempted coup for the Trinidad Guardian, every negative had disappeared. All that’s left are three work prints I made to remind myself of that week under machine-gun fire.

It’s trying to hold sand in running water and it happens almost continuously.

Rocky McCollin’s record collection is being held by his son, Roger.

George Maharaj confirmed, in a call from Canada that his 7,000 album collection of calypso, pan and parang records is stored by his son in spare rooms of his house.

Maharaj who is 76 this year, has lived abroad since 1969, visiting for Carnival each year. Barbados briefly expressed interest in his album collection in 2008 and the late PM Patrick Manning had discussions with him, but nothing has ever materialised.

Our continuing national mistake in art, culture and journalism has been to treat the final product as the only product. There may be a determined few who have held on to finished calypso recordings, but there are no alternative takes, no unreleased songs, no extended versions.

Reissues are impossible. Remixes are inevitably re-recordings because original tapes and masters are long lost.

What is special about the Banyan archive is the scope of what was kept, not just the broadcasts, but the source material that informed them.

Carnival’s architects, the NCC and stakeholders, create rules and an institutional framework that’s designed to stymie a thoughtful record of the festival, make no effort of their own to even pretend to preserve or record the work that’s created and allow each year’s output to vanish with a devastatingly final flourish of indifference.

The embarrassment of repeatedly losing this country’s creative assets and history isn’t as worrisome as the continued lack of any strategy to change that humiliating status quo.

Let’s be clear. Creatives who are arrogant enough to preserve their work are not just ignored, they are actively punished with casual requests for freeness seasoned by a sense of entitlement to “de culture,” any evidence of which would simply disappear if it depended on the existing national agenda for preservation.

Great content, thanks for posting.