- The introduction of Fixed Number Portability (FNP) in Trinidad and Tobago is nearly pointless.

- Number portability in Trinidad and Tobago has been delayed since its announcement in February 2016.

- Questionable need for number portability outside of businesses.

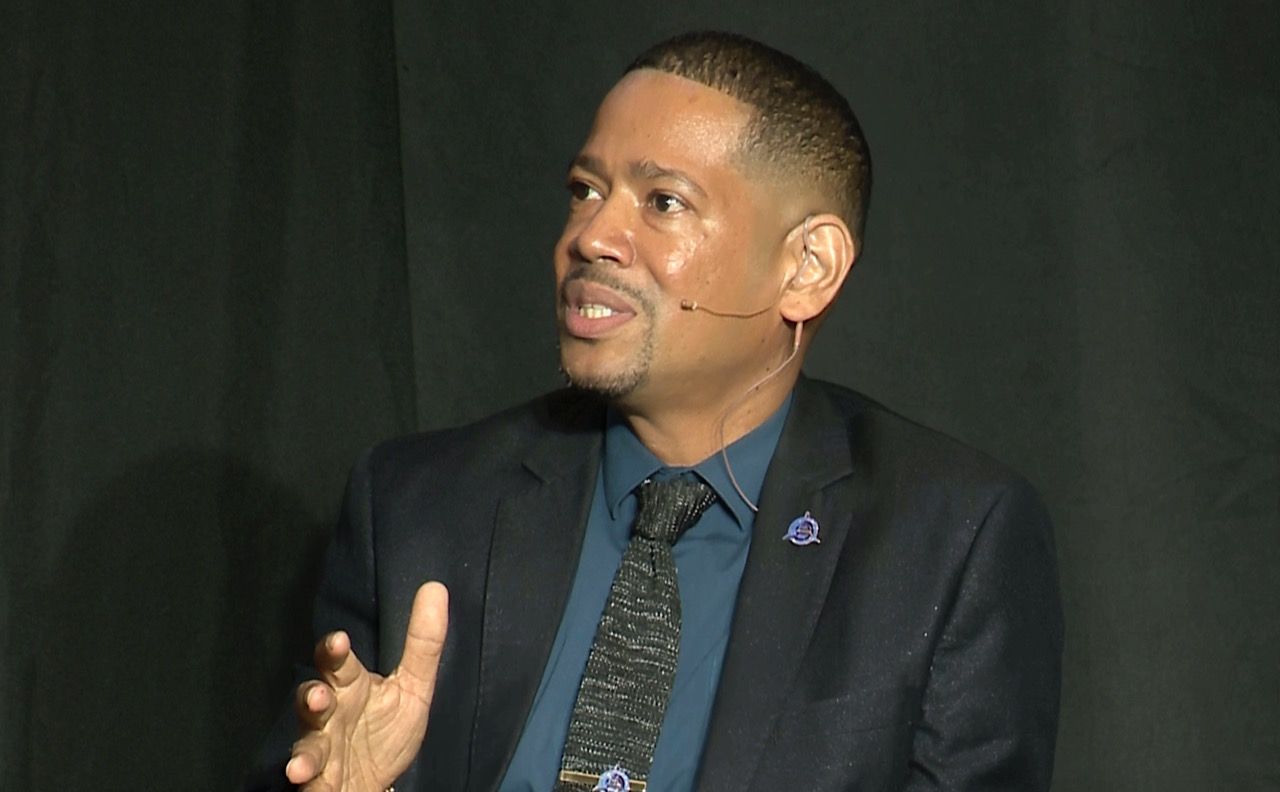

Above: Minister of Public Administration and AI, Dominic Smith.

BitDepth#1517 for June 30, 2025

The introduction of Fixed Number Portability, the ability of fixed line users to change providers without losing their phone number, is not a completely pointless announcement, but it’s very nearly so.

The entire history of number portability in TT is one that is governed by the military term OBE (overcome by events), the things that happen when neat plans collide with reality.

Some background might help.

The Telecommunications Authority of Trinidad and Tobago (TATT) announced that it would be introducing number portability to the market in February 2016.

Yes, the initiative was first promised to the public within shouting distance of ten years ago. [Updated insider note, I am advised that the number portability project began in 2013, and the first delay happened in 2015. It was announced to the public in 2016.]

Jamaica had already rolled out its own number portability project in 2015, porting 60,000 numbers.

In April 2016, TATT announced that the project to start Mobile Number Portability (MNP) had been delayed, then announced another delay in July.

Finally, the authority, known for an excessive and often unmerited patience with its recalcitrant licensees, set a deadline of October 2016 for the commencement of the project.

In its official statement on the matter, TATT noted that the deadline for mobile to mobile number portability would be October 31 and fixed to fixed number portability would be November 28, 2016.

“The Authority,” the official notice said, “declares that it shall cease forthwith to exercise forbearance on non-compliance by Operators who are subject to this DETERMINATION (sic).”

So naturally, all licensees, worried that they might have their ability to operate pulled out from under them, rushed to do the regulator’s bidding, yes?

BWAHAHAHAHA. Noooo. They did not.

A statement from the authority issued in July 2021 expressed the hope that good sense would prevail after TSTT’s resistance to FNP had gone to court.

“Given today’s judgement TATT intends to move promptly to implement Fixed Number Portability and work with TSTT and other fixed telecommunications service providers towards that goal,” TATT proudly declared.

This court case followed a July 2020 injunction filed against TSTT by Digicel complaining about the slow pace of number portability experienced by its customers.

Having agreed to MNP, Digicel argued, TSTT was deliberately dragging out the process to frustrate potential migrants from its network.

In its submission, Digicel noted that “Between January to June 14, 2020, a total of 9,274 porting requests were submitted by Digicel. There were 2,223 rejections for the six-month period.”

That matter was bounced back to TATT for “specialist intervention” after the Appeal Court upheld a decision by Justice Nadia Kangaloo.

For those with a taste for legal judgements, reporting on Justice Frank Seepersad’s findings is here.

So it’s not a simple matter of TATT announcing number portability in 2016 and then announcing it again in 2025.

The telecommunications landscape is also fundamentally different today.

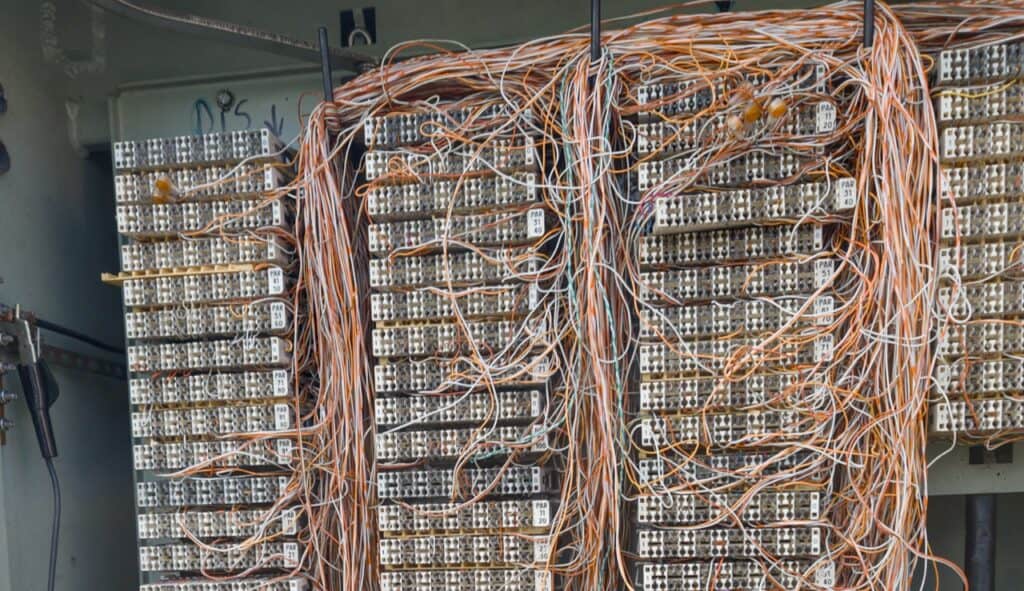

In 2016, TSTT had many customers connected to a copper hardline network. In September 2018, the company announced plans to entirely replace that network with fixed 5G connectivity or WTTx (wireless to the whatever).

In April, TSTT announced that it was testing Voice over LTE, essentially Voice over IP for mobile, which it should also be able to deploy on its next generation network.

The copper network was aging out, could not support modern connection speeds and was vulnerable to theft, because there is a healthy aftermarket for the metal.

The company knew it was a problem since 2006, when a two-year project to replace copper lines with fiber optic cable was underway.

By 2019, the company was talking about all the advanced technology applications that WTTx would deliver, beaming a live video stream from the Hyatt to TV6 using a device that would fit in a backpack.

Nobody has used the technology for that kind of point to point transmission ever since. WTTx has been deployed to create a WiFi mesh in some public areas as a time limited public good.

But one is likely to get off track and stumble into the bushes of proud announcements that lead to no practical applications.

TSTT’s Zero Copper campaign did not take 18 months. It is still underway.

In St James where I live, it took more than a year to complete to the point that copper switches could be removed from sidewalks and that project didn’t even begin until 2023.

[Update, June 30, 2025: TSTT responded to this column to note that its Zero Copper project is approaching 100 per cent. A company statement clarified that residential and single line business customer migrations are 97 per cent completed and enterprise business customer migrations are 99 per cent completed.]

When a technology is announced and then languishes for a decade, other things happen. Digicel and Flow proceeded to create their own fixed network on top of their cable offerings.

Anyone who didn’t want to wait on WTTx either went to the competition or just used a mobile, where WhatsApp also eliminated the cost of long-distance charges, a powerful lure for grandparents who might otherwise look at a mobile phone askance.

Last week’s grand announcement by TATT and the Ministry of Public Administration and AI did not offer any statistical history to support number portability excitement.

How many mobile numbers have been ported and from which providers? How many “landline” customers are actually left?

There is no reliable way to evaluate what the market for fixed numbers is currently. [Updated: TATT’s CEO Kurleigh Prescod has clarified since publication that the authority is aware of 300,000 fixed line customers. An average of 5,000 ports per month are executed for MNP, a market with 1.8 million subscribers.]

Over the last nine years, the once voluminous TSTT directory of homes and businesses the authoritative listing of customers connected to copper hardlines shrank until the private line phone book disappeared entirely. The commercial phone book was last published in 2022. The online Yello service operated by TSTT is janky at best.

OBE issues are relevant because we can’t talk about number portability without considering the actual market for the service. Apart from businesses that want to hold on to vanity or well-distributed numbers who needs FNP?

This isn’t TATT’s problem. As a regulator, they enable technologies that are meant to benefit consumers.

TATT is currently field testing digital transmission for over-the-air television transmission which will deliver HD video, improved audio and other benefits, but again, who is the expected market?

Streaming services and cable services already offer these benefits and local television offers little to compete with those offerings. Fans of news presenters might welcome HD visuals of news delivery, but where’s the market?

There has also been no discussion about the regulatory underpinnings that will cement this refreshed, if likely foolhardy effort at FNP to firm legal ground.

One of the sticking points of the 2021 case was official concern about the regulator’s legal footing to compel.

Last week’s FNP announcement brought praise from the AI Ministry’s reliable cheerleaders and new eat-ah-food hopefuls, but they are actually celebrating a disastrously overdue announcement in a decade long catastrophe of botched implementation that looks set to benefit almost nobody.