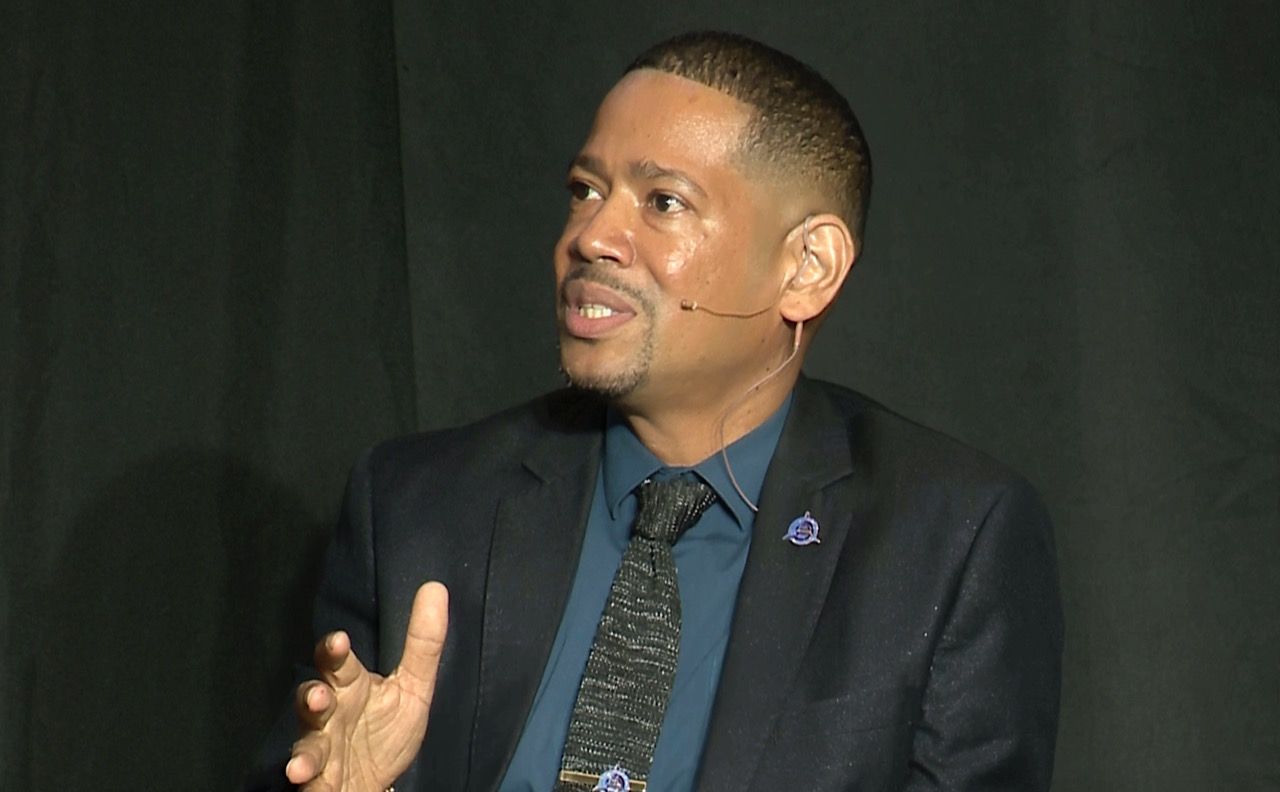

Above: Ron Haviv.

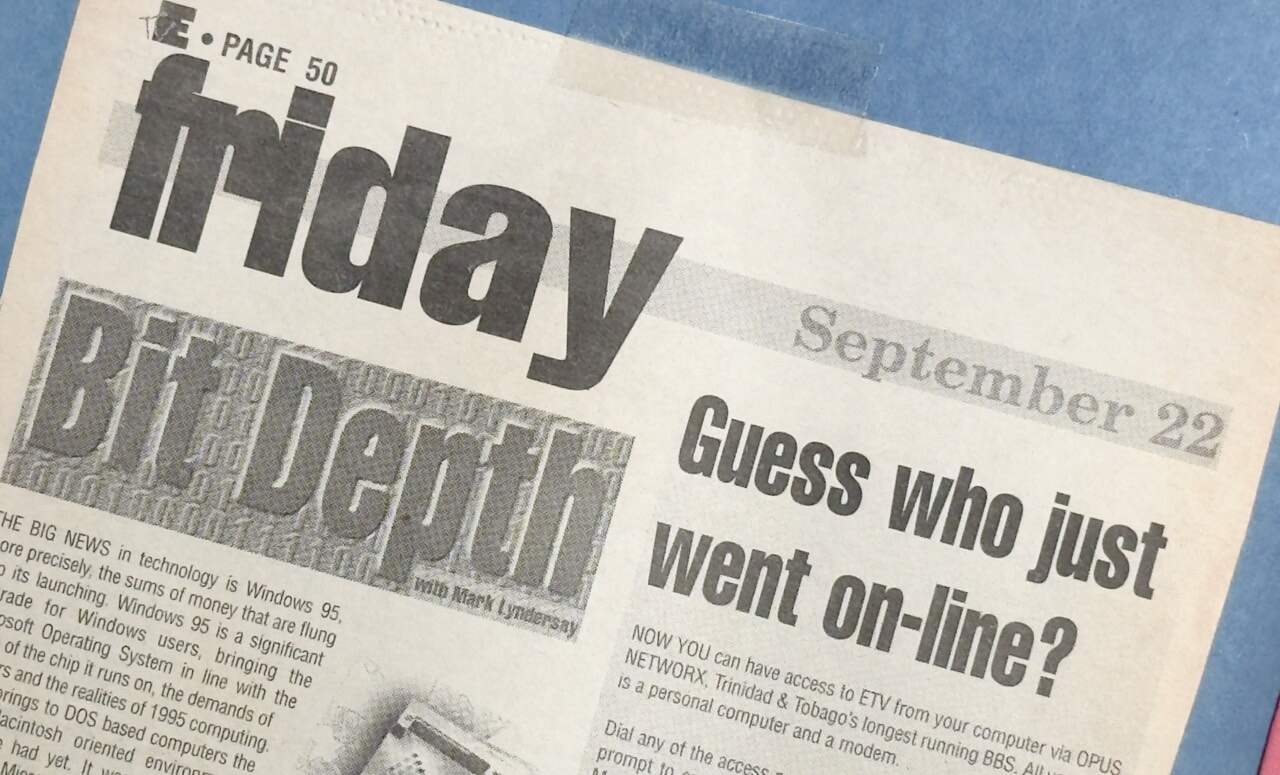

BitDepth#1427 for October 09, 2023

Santiago Lyon, a former vice-president at the Associated Press, noted that Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) began in 2019 as an open source project to address distrust of news and particularly images and video.

It isn’t Adobe’s first effort at open-sourcing its technologies. The portable document format (PDF) and the digital negative format (DNG), both sought to bring open access to document and raw digital image formats respectively.

While PDFs are widely used and there is some adoption of DNG, most recently as a preferred format for smartphone raw files, the planned CinemaDNG format crashed ignominiously and Adobe doesn’t talk about it anymore.

“We identified four main areas starting with detection, which involves uploading suspect files to programs that look for telltale signs of manipulation,” said Lyon, who is now Head of Advocacy and Education for CAI at a September 19 webinar.

“We deliberately decided not to get involved in the detection game, in part because it’s not scalable. It’s also not particularly accurate and ends up as an arms race with bad actors staying one step ahead of the latest detection software.”

“We chose to focus on three other areas. Policy, which involves briefing policymakers and lawmakers around the world to make sure that they’re up to speed with the latest technologies.”

“[We also offer] advice and education that’s focused on media literacy and consumer literacy, but what we’re really focused on is the notion of provenance. [CAI wants to make the] origins of digital content, whether images, video, audio recordings or other file formats transparent, showing the viewer where and how the files were created, what changes might have been made to them along their journey from creation through editing to publication.”

“We’re working with hardware manufacturers to integrate this technology into their devices at production soon. When you buy a camera or a smartphone, the goal is that it would ship with CAI technology installed on it. “

In the face of generative AI image manipulations and AI powered image alteration tools that make falsification easy for novice users, journalism faces real challenges in ensuring that readers and viewers can trust what they see as a representation of the truth.

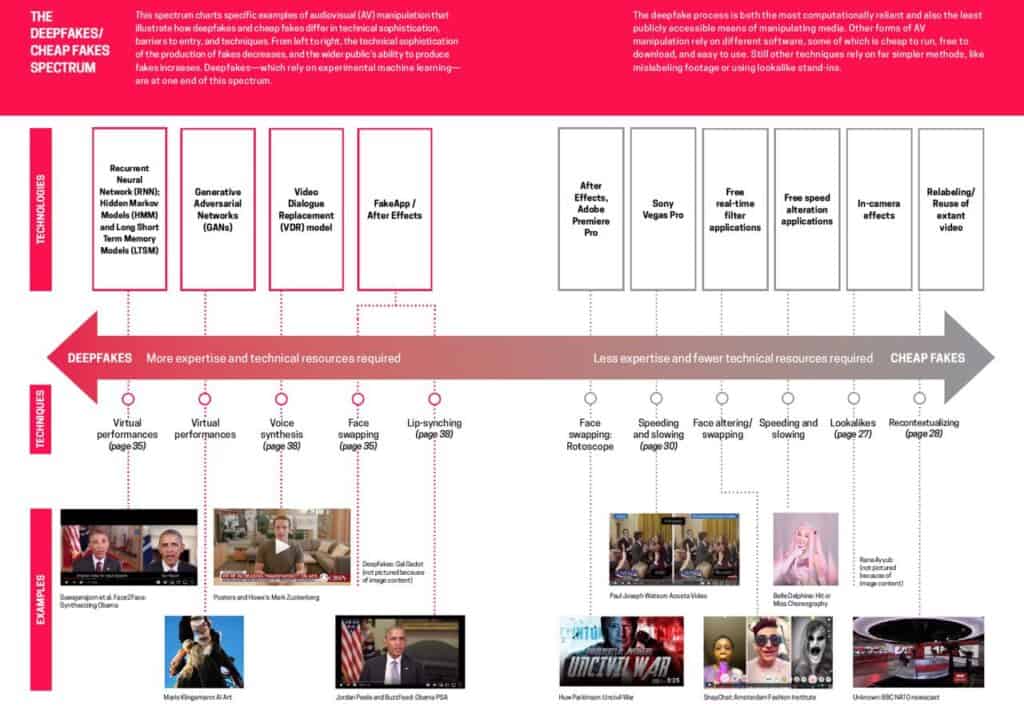

Despite concerns about image manipulation and video deep fakes, which use video manipulation to falsify motion clips, Ariel Bogle, Investigations Reporter at the Guardian Australia warns of the greater pervasiveness of cheap fakes.

“This is content that is real video that’s been filmed at some point in time that now has been removed from its context. Maybe it’s been slightly edited, slowed down, pauses on someone’s face when they have a strange expression to suggest that they are evil or lying to the public.”

“Cheap fakes end up recontextualizing imagery, using basic effects which most people can access and use, speeding up, slowing down, adding colour filters to give a dingy or sinister aspect to videos.”

Photojournalist Ron Haviv of the VII foundation explores how this happens in a documentary of his 30-year-old photo of violence in Bosnia which has been decontextualised, misrepresented and used as propaganda. Haviv is using CAI to tag the digital version of the brutal photo.

“Fake News is an insult. In this case, it’s an insult to those who die. My documentation of a war crime in Bosnia of well-armed Serbian paramilitaries executing unarmed Muslim civilians is a perfect example of an image that needs to be believed then and also really needs to be believed now.”

“CAI can and should be used even for an analog image to create a digital provenance that has to exist today to fight against the permissive and ever strengthening idea of revisionism, the idea of fake news.”

“When the war in Ukraine started in 2014, a very well-known Russian blogger took the photograph and simply changed the caption to say that the victims were Russians. The perpetrators were Ukrainians. He posted it to his audience, and it went viral throughout Russia.”

“Now if you show that photograph to an average Russian, if they recognise it, they’re going to say this is a war crime against Russians done by Ukrainians.”

“If we, as a community of visual journalists, lose the trust of our audience, they just say like, oh, that’s been photoshopped, the tragedy becomes the stories of these people are not believed.”

“It’s important to also understand that the images that we’re seeing, they’re not just made-up of pixels, they represent real people.”

“When you break that chain, when you break that trust, then we’re in great danger.”

Getting traction for CAI implementation on the scale that is required, from hardware manufacturers, software programmers, creators and consumers is a staggering task.

There are also certain classes of users who want to eliminate provenance for legitimate reasons. Journalists in a war zone would prefer not to share files that embed their GPS coordinates.

A human rights activist would not necessarily want to be identified with a damning document. Other users may simply prefer anonymity or privacy.

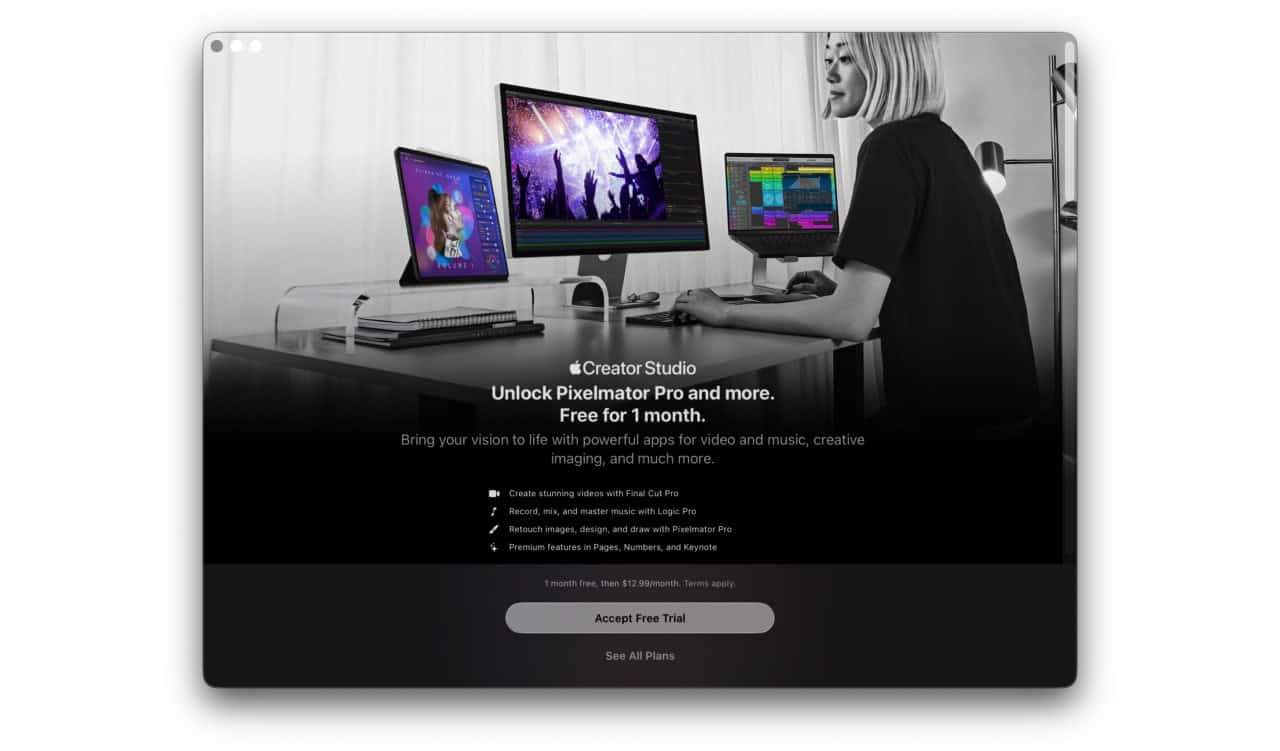

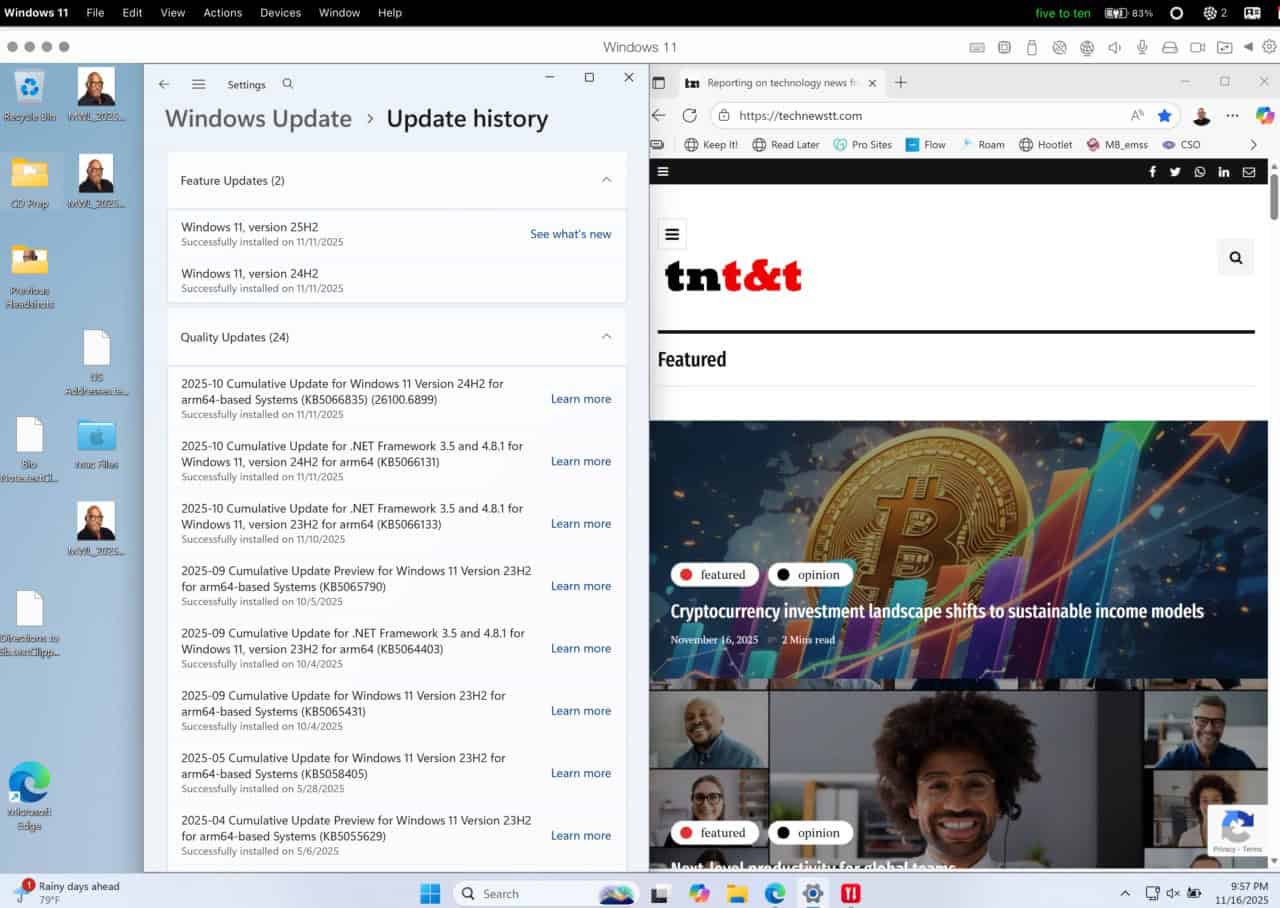

The end use case of implementation would be a CAI icon that the viewer can click on to see what has been done to the image since its creation, a feature that’s leagues beyond the simple rights identification exercise that Creative Commons licensing has been trying to bring to the online imaging community with only marginal success since 2001.

Lyon notes that the primary markets for the technology are news producers, e-commerce, medical and satellite imagery and the insurance and law enforcement industries.

[…] Caribbean – Santiago Lyon, a former vice-president at the Associated Press, noted that Adobe’s Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI) began in 2019 as an open source project to address distrust of news and particularly images and video… more […]