- USB, introduced in 1996, replaced serial and SCSI ports.

- USB never achieved its theoretical maximum speeds, even in ideal conditions.

- Newer cables have distinct logos and printed specs, older cables lack clear identification, their capabilities a mystery.

Above: USB-C plug. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1524 for August 18, 2025

Consider the longevity of the humble Universal Serial Bus (USB) port.Consider too all the ways it has failed to live up to its promise despite that.

The serial port had a solid ten-year run between the 1980’s and 1990’s.

The Small Computer System Interface (SCSI) port lasted a bit longer, running from the mid-80’s before peaking in the mid-1990’s then fading out by 2000.

The obvious successor to these connection protocols wasn’t obviously USB when it was introduced.

The pervasive letterbox port (USB Type A) arrived in 1996 with a top transfer speed of 1.5 Mb/s, achingly slow by today’s standards, but a good match for the smaller files and drives commonplace then.

That connector is still in use today, though it’s been revised continuously. USB2 raised transfer speeds to 12, then 480 Mb/s by 2000, when the connector was challenged by alternative connection systems, including FireWire, eSata and Apple’s proprietary Lightning connector.

USB quickly made the jump with USB3 to 5Gb/s speeds in 2008. USB3.1, introduced later in 2008 doubled speeds to 10Gb/s. Then USB3.2 in 2017 brought a top speed of 20Gb/s.

All the improvements from 2008 onward bore the unhelpful label of “SuperSpeed.” Few connectors offered clues about their capabilities.

While those aspirational speeds were theoretically possible, they were never actually attainable, even in perfect conditions.

Conditions were never perfect. Worse, if any component of your connection chain was a mismatch, if you connected a USB3.2 cable to a USB3.2 computer port and then connected that to a USB2 hard drive, the entire chain dropped to USB2.

This naturally caused some annoyance and frustration. The connection would usually work, but slowly.

Today’s USB-C was a great idea. It dispensed with all the variations that USB had dallied with over the years between 1996 and 2002.

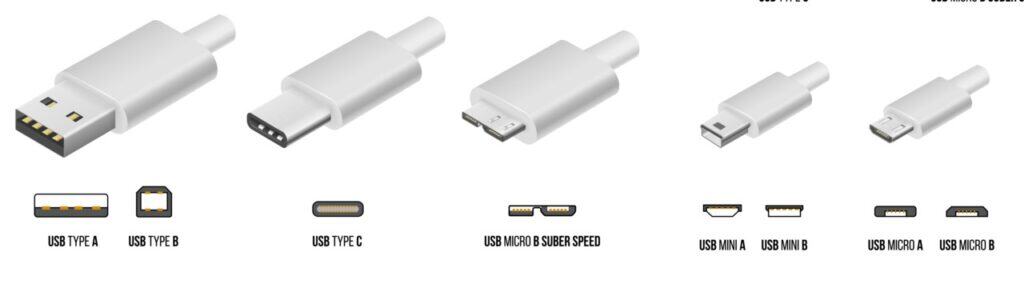

There are still devices manufactured that include USB Type A letterbox ports, Type B, Mini A, Mini A-B, Mini B, Micro A, Micro A-B and Micro B.

The micro ports were mostly used charge phones, while SuperSpeed mini versions were used on slimline devices like external drives and CD burners.

The new USB-C port was reversible, like Apple’s Lightning plug, it didn’t matter which side was up.

The specification was designed from the start to provide power and allow data transfer, including video signals. It should have been a bold path out of the jumbled tangle of cables we were living with.

When Intel used the port for its fast Thunderbolt specification with backward compatibility for older USB connections, the one cable to rule them all seemed to be within our grasp.

It was not.

USB-C cables shipped with smartphones were often cheap and delivered power, but limited or no data transfer at all.

Apple’s iPhone 16 has a USB-C port, for instance, but transfers data at USB2 speeds, an appalling 480 Mb/s while the iPhone 16 Pro, using an identical port, transfers at USB3.1 speed, 10Gb/s. You have no way of knowing this without scrutinising the phone specifications.

As smartphones evolved and the need for faster charging became desirable, cables that supported the Power Delivery (PD) specification were required, but this was also often shoddily implemented.

It wasn’t unusual to connect a PD-rated charger to a PD-rated cable and have the phone complain about low power.

This has become an even greater concern as both power demands and USB PD protocols have evolved. USB A once transferred 0.5W of power, a modern USB4 PD cable can deliver 240W of power.

The USB Power Delivery Programmable Power Supply specification, at least marginally supported by higher-end third-party power supplies helps them to be smarter about how they allocate power across multiple ports.

All these problems are supposed to be fixed with USB4, the newest USB-C specification. USB4 also matches specifications with Thunderbolt 4 and 5, which can transfer up to 120 Gb/s and deliver 240W of power, while supporting high refresh rates on large screen displays using DisplayPort 2.0.

All this could have been avoided right from the start by mandating simple iconography on USB-C plugs and ports to identify their capabilities.

A Thunderbolt cable is required to have a distinctive lightning bolt symbol on each plug and USB4 cables have a distinct logo. Forward-looking cable manufacturers are printing cable specs directly onto these new plugs.

Unfortunately, older plugs remain a sketchy wire tangle. It’s impossible to guess the capabilities of a USB-C cable manufactured prior to 2024 without testing it until it fails to do something expected of it.

I’ve got dozens of these mystery cables that I assume are only capable of low wattage charging and eventually they will all be dumped. That didn’t have to happen.