Above: It doesn’t seem that long ago that Wired magazine was calling for prayer for Apple and Michael Dell advised Apple’s board to sell the company and give the shareholders back their money.

BitDepth#1452 for April 01, 2024

On March 21, the Anti-Trust Division of the US State Department filed an 88 page complaint against Apple, alleging that the company was engaged in anti-competitive actions to the detriment of the public.

The complaint notes – without irony – that it was an antitrust case against Microsoft that made it possible for Apple to distribute its iTunes software, then necessary to communicate with its iPod music player, on the Windows operating system, steering the company, then routinely described as “beleaguered,” back to profitability.

Today, the sheer scale of Apple’s profitability since introducing the iPhone is now a concern for the State Department.

Apple, once on the verge of bankruptcy, is now the second most profitable company in the world, earning profits of US$99.8 billion in 2023 behind Saudi Aramco who made $151 billion. Apple operates with sizeable margins across all its product lines and has a robust hold on the mid to upscale market for smartphones.

The iPhone may be the company’s flagship, earning 52 per cent of the company’s revenue, but it’s Apple’s second largest money spinner that seems to have drawn the attention of the US government.

Apple’s services, including AppleTV, Apple Music and Apple Pay, account for 22 per cent of the company’s revenue and it’s drawing the lion’s share of the concern articulated in the 88 page document.

To be fair, Apple has been pretty heavy-handed in protecting its moneymakers, ejecting Epic Games and its hit game Fortnite from its App Store because the gaming company wanted to establish its own payment systems within the game, bypassing Apple’s restrictions and 30 per cent fee.

That fee has long been a sticking point with developers along with Apple’s insistence that software on their app store must adhere to more strict programming guidelines.

Here’s where some personal experience factors in. I’ve long been a fan and supporter of special purpose, single task tools that zero in effectively on computing problems.

I’ve spent a small fortune, or to be more accurate, an unholy number of tiny payments to small shop, individual developers who create software I find particularly useful over the last 30 years.

Only a few of the more adventurous of these developers are present on the company’s app store and many must jump through coding hoops when Apple changes the programming interfaces in its operating system.

For a user with less of a taste for the wild side of software programming, Apple’s online software store does offer a range of special purpose small apps in a curated environment that safeguards anyone downloading software there.

Some developers create a sanctified version of their software that passes app store scrutiny while offering a more capable, but edgier version that’s usually available directly on their website without the 30 per cent fee that Apple levies.

More user experience. At the end of 2023, after more than 12 years of using an Android phone with a Macintosh computing system, I got an iPhone again.

That decade of experience navigating a mixed computing environment meant making some careful choices around software that worked on multiple platforms, but there is unquestionably something compelling about living entirely inside Apple’s walled garden.

Phone calls, for instance, ring everywhere. On the laptop, on the iPad on the iPhone. Hell, even on the watch. There’s software that made that happen on a Mac and an Android device, but it was pretty expensive for just that added convenience.

Apple’s spirited protection of and continuous improvement to its intimate binding of hardware and software is key to its profitability. The company earns more than 70 per cent of its revenue from a combination of iPhone sales and services designed to enhance it.

Google, by comparison, earns 57 per cent of its revenue from search and another ten per cent from YouTube.

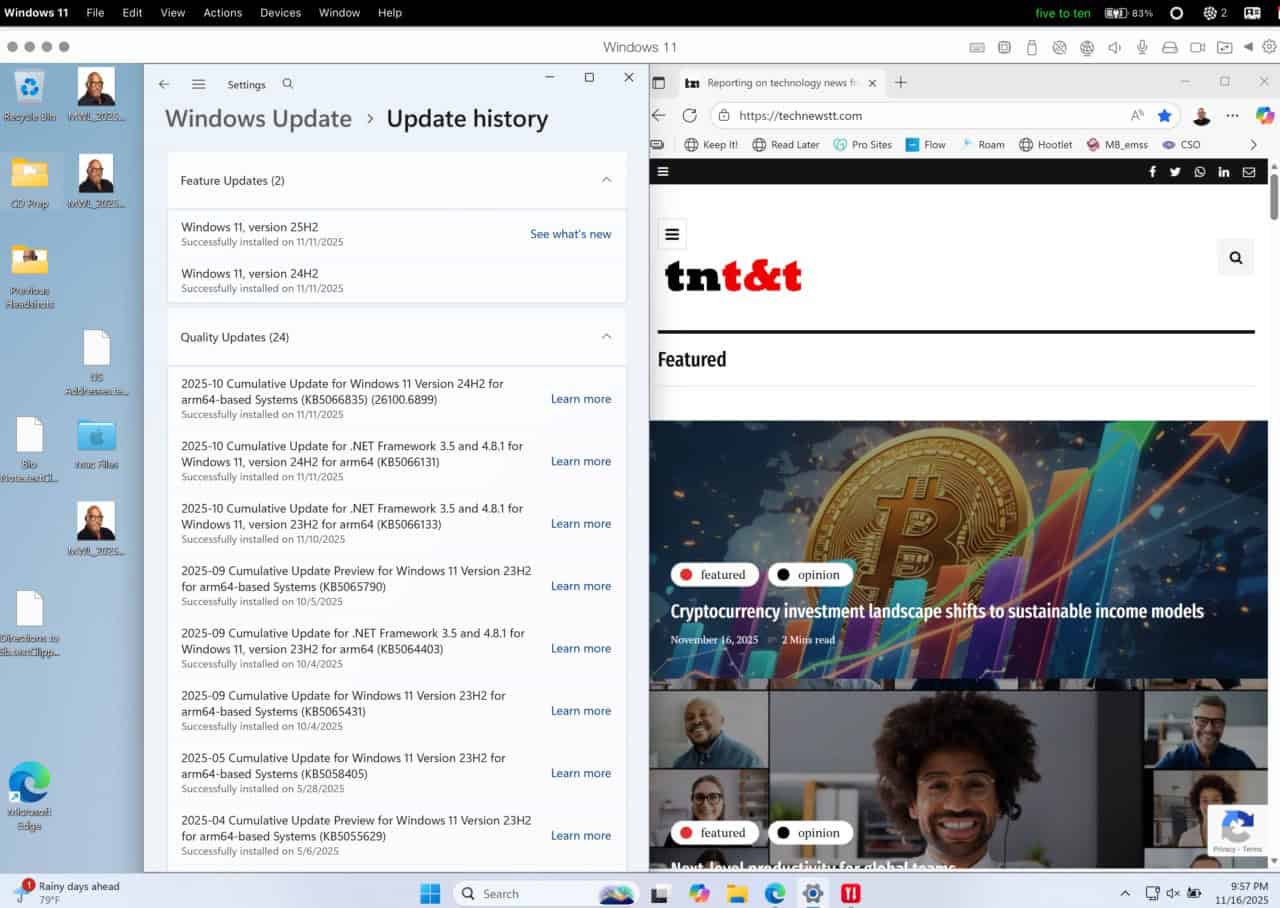

Sixty per cent of Microsoft’s revenue comes from cloud products for the office and server operations with Windows pulling in another ten per cent.

Amazon earns 42 per cent of its revenue from its online stores and another 22 per cent from third party sellers who do business on that platform.

Facebook earns 98 per cent of its revenue from advertising on its platform.

It should come as no surprise that each of these companies vigorously defends the jewels of their crown and each has earned some level of scrutiny from the state department which views these successes as potential monopolies in their sectors, though it also hints at the cumulative nature of avalanche technology successes.

More open software environments benefit all users, as the state department’s complaint argues, but Apple’s software ecosystem isn’t as closed as the complaint insists, though this action may encourage some welcome loosening of its unnecessarily exclusionary restrictions and shake some percentage points loose for its developers.