- Businesses face challenges when critical software runs on outdated, unsupported hardware, leading to potential system failures and compatibility issues.

- Software developers prioritize new hardware and operating systems, leading to compatibility issues.

- Linux relies on community support and crowdsourcing, which is not sustainable for commercial computing.

Above: Weighed, but never found wanting. The last duty of failed 2009 MacPros, going to an aluminium recycler. Photos by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1498 for February 17, 2025

Into every technology reliant business some rain must fall. Sometimes it’s a downpour; a hardware upgrade and the attendant software challenges come bobbing along in the muddied waters.

In enterprise, the problem usually arises when a business must confront the end-of-life of a critical business app that runs on outdated, hardware that’s no longer upgradeable.

It’s possible to run legacy (also described as museum or archival) systems long past their reliable technology lives, but even the most reliable hardware will eventually fail.

The problem can also manifest in required supporting software, making its continued use problematic or straight up impossible.

There are potentially apocryphal stories of businesses that were unable to find critical server systems on their premises, only to realise after trailing their network cabling that they system was in unusual spaces, hidden by drywall or lost among a massive installation of newer hardware.

The story of a Novell server that hadn’t been seen for four years at the University of North Carolina that was eventually found behind a wall by a maintenance crew is the standing benchmark for such tall tales.

Even if it happened, it’s unlikely that anyone at the university would ever admit it.

So here’s my confession. Since 2011, I’ve been running a cavalcade of machines capable of supporting Mac OS High Sierra (10.13) for one reason, I refuse to subscribe to Adobe Photoshop.

That was the last stable version of the OS that supported my perpetually licensed copy of Adobe Photoshop CS6 and Lightroom 6.

I’d kept that copy of the image editor running across multiple system updates until hitting that OS compatibility wall.

Over those years, I used two consecutive 2009 MacPro towers, an iMac Pro and finally a 2013 MacPro, the infamous “trashcan Mac.”

It was a simple choice. Keep using the old thing that I was comfortable with that wasn’t broken or go through the pain of learning a new thing that aligned with modern standards.

Eventually, it was everything except the old copy of Photoshop that caught up with me. Services I couldn’t connect to anymore. Browsers and other software that couldn’t be updated.

Even forked open source software committed to maintaining usability on older systems was beginning to show insurmountable cracks.

What followed was a serious month of running Photoshop alternatives to find a workflow that could replace one that had been worn in over almost 35 years of digital photography.

Unlike enterprise computing systems, which can be tasked with a single digital requirement, a computer system in a home office must deliver multiple services to earn its keep and the cumulative failure of those ancillary tasks can begin to put an ever heavier hand on the scales of a decision to retire a legacy system.

I’ve seen many systems continue in use well past their anticipated useful lives, but when I see them, it’s usually because their users are having an intractable problem with required software.

The useful life of a modern computer is around five years. Most software and operating systems will support five-year-old hardware. Ten years is the outside age for a computer system. At that point, software developers have moved on.

Operating system developer teams can’t grapple with the demands of new hardware while maintaining compatibility with older iron.

Authorisation and activation servers get shut down and perpetually licenced eventually means nothing at all.

Connection ports will also be dramatically out of sync with modern realities and may not even exist anymore.

Even when the connectors work, they may not work how the user expects. USB-A, for instance, delivers a range of speeds from USB1 (1.5 megabits) to USB3 (5 gigabits).

To help with the considerable confusion that creates, modern USB-A ports are usually colour coded, but the further back the hardware goes the slower the likely connection speed.

The system might have Bluetooth, but a Bluetooth v2 radio on the motherboard means that your fancy headphones will connect at that speed. The slowest part of the chain, the port, the cable, the supporting chipset sets the pace.

The only OS that caters to systems that old anymore is Linux, which is buoyed by a spirited community and managed crowdsourcing, a nonprofit model that’s not sustainable in the commercial computing industry.

There are code patches that allow older computers to run current operating systems, but they are, to put it kindly, hacks that remove blocks that are sometimes arbitrary.

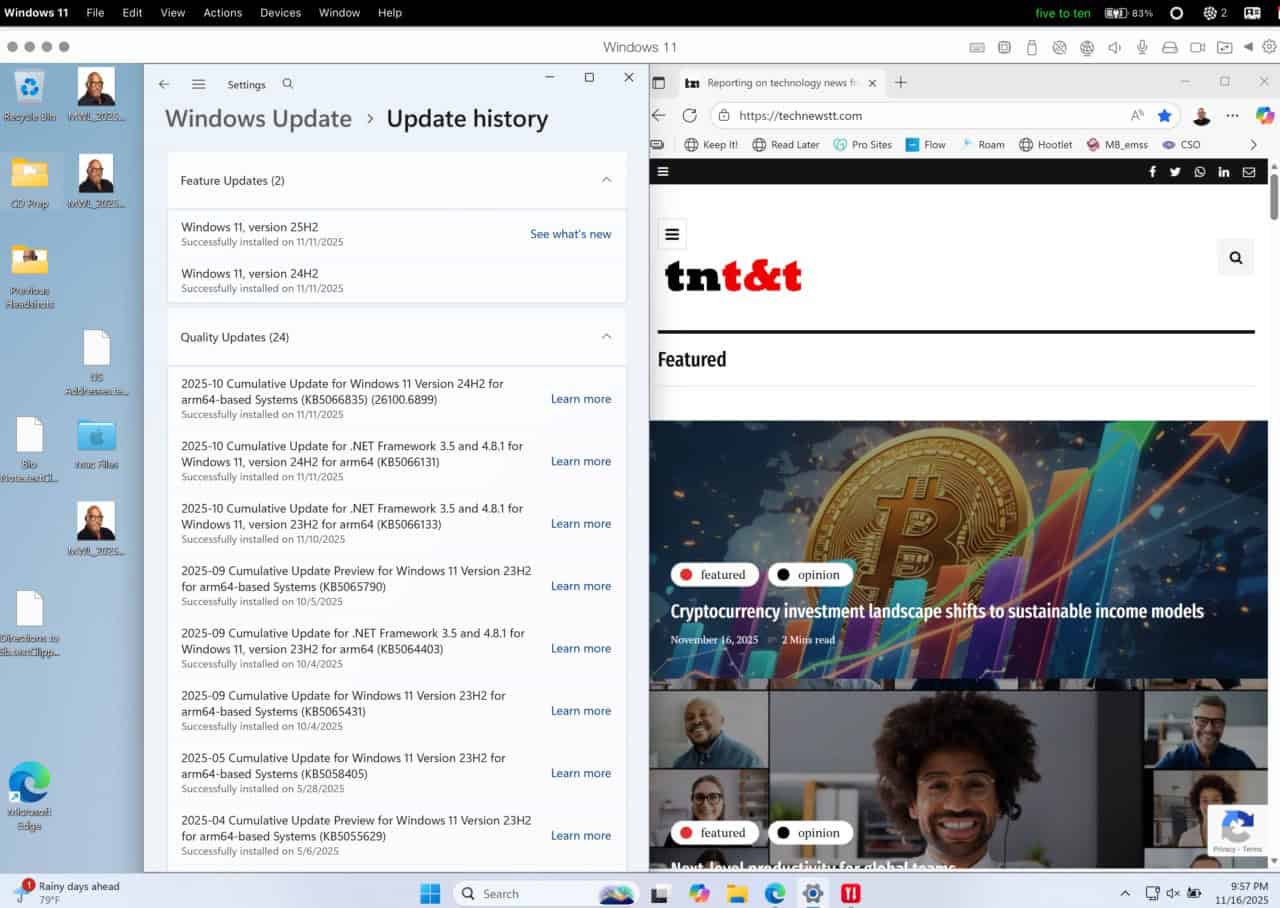

This particular column leans in heavily on MacOS, because that’s where my experiences are, but the broad issue obtains across computing platforms. It’s arguable that I got away with what I was doing so long because of that. An equivalent Windows installation would have been troublesome to keep secure.

I’m currently keeping a well-kitted 2013 iMac running with a recent version of MacOS using an unusually slick code patch called OpenCore that’s only improved steadily over time, so much so that it feels more like an OS feature than a code hack.

The migration path to my current upgrade forced a more flexible workstation architecture as I went along.

The 2009 MacPros could host seven drives (one on a PCI adapter) in one massive case. The iMac Pro forced a division between computer and storage that proved to be a good idea. That 2013 MacPro underlined the need for a fast connection between storage and computing system (it used slower Thunderbolt 2).

Another consequence of this incremental effort at upgrading has been the notable shrinkage of the hardware. The workstation replacement is the M4 MacMini, which handily outpaces all its predecessors in a form factor that fits comfortably in my open palm.

The 2009 MacPro, by comparison, required both hands and lifting with my knees.

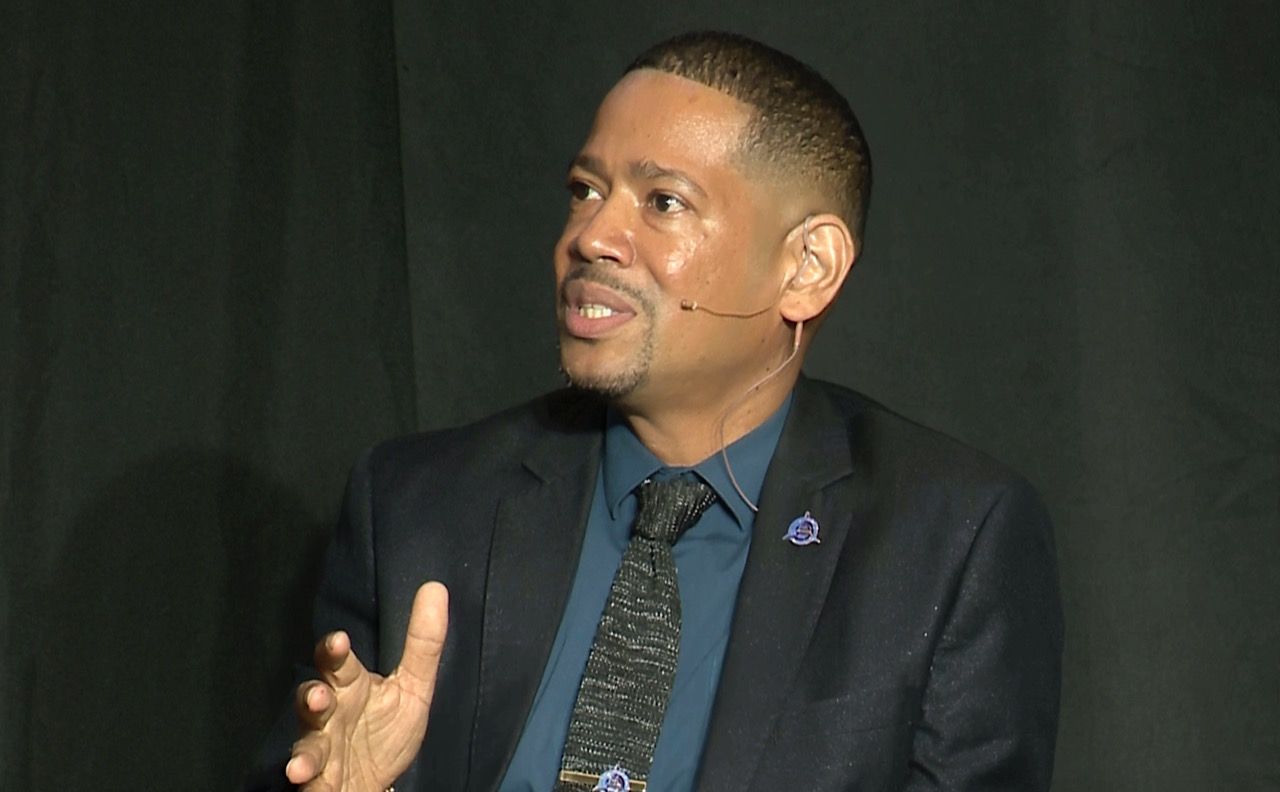

Forgive me if I don’t understand the difference between one model of Mac to another. I have never owned a Mac. Never wanted to.

In fact, when I first encountered the original 128K Mac, I was appalled that anyone would ever want one.

Time passed and I realised that, yes, there are people who want Macs. Go figure.

I have, of course, from time to time, used a Mac, usually somebody else’s Mac, but my opinion has not changed.

I think I saw from the beginning that the trend in computing was ALWAYS to move towards more vendor lock-in, not less.

This was true even before I was born and it certainly is true now.

So, this day when you have come to the point of incompatible hardware and software, was inevitable all along.

But we know this. Richard Stallman has spent his life since the 1980s, like a prophet of doom, telling us this over and over again. He spent his US$250,000 MacArthur grant setting up the FSF and GNU because he foresaw the inevitability of this situation.

I got up this morning and Cory Doctorow was ranting about the “enshittification” of the internet at DefCon32.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EmstuO0Em8

That boils down to the same thing.

And even though you state that Stallman’s solution is “not sustainable in the commercial computing industry”, it has endured and continues to persist regardless.

I don’t feel sorry for your plight. As my wife says, you bought that wholesale.

And yes, your road forward is either pay the subscription or learn a new workflow with supposedly inferior tools, but we live in an imperfect world and it isn’t going to change unless we change it.

Richard

I hear you and respect your point of view. I certainly don’t champion any adversarial perspective toward open source software or, for that matter Windows. It seems to me a better thing all around for there to be choices, even if some of those choices are limited by design. I read Doctorow’s original screed on that subject. I believe he is correct, particularly in the way and the speed with which that process overtakes commercial ventures like social media.

My plight, as you describe it, is one more marker in my journey with technology and its impact on society. I certainly don’t bemoan the situation, having charted the arc of the process some time ago. The point of the column has always been to share my own real-world experiences with technology, good, bad and just plain annoying.

Wouldn’t have minded a PSU from one of those towers

You could have had all. I’m not sure if they all worked, but the failures were almost universally the motherboard. Pity. Recycled scrap now.