- The strategy lacks timelines, project details, progress reports, cost estimates, and internal evaluation insights.

- The government should facilitate innovation through governance and legislation, but has failed to do so.

- The government’s approach to Open Data is unclear, lacking a strong Open Data dashboard and incomplete data availability.

Above: The cover of the Digital Transformation Ministry’s strategy document.

BitDepth#1493 for January 13, 2025

The Ministry of Digital Transformation (MDT) published its National Digital Transformation Strategy for 2024 – 2027 and it is, in a word, an embarrassment.

Under the title BOLD (Building Our Lives Digitally) the MDT proceeds, over 88 pages that manage to be both verbose and vague, to rehash the talking points it has been spewing with great enthusiasm ever since it began communicating with the public.

It’s notable that the document includes not a single photo or chart to support even a single project undertaken by the ministry since its formation under Hassel Bacchus in August 2020.

In his introduction, Minister Bacchus restates his ambitions for a “Digital Government that collectively offers a new way to address the end-to-end consumption and delivery of goods and services to customers using appropriate digital technology.”

He goes on to revisit previously stated notions of how this is to be achieved via the concepts of a digital society, digital economy and digital governance.

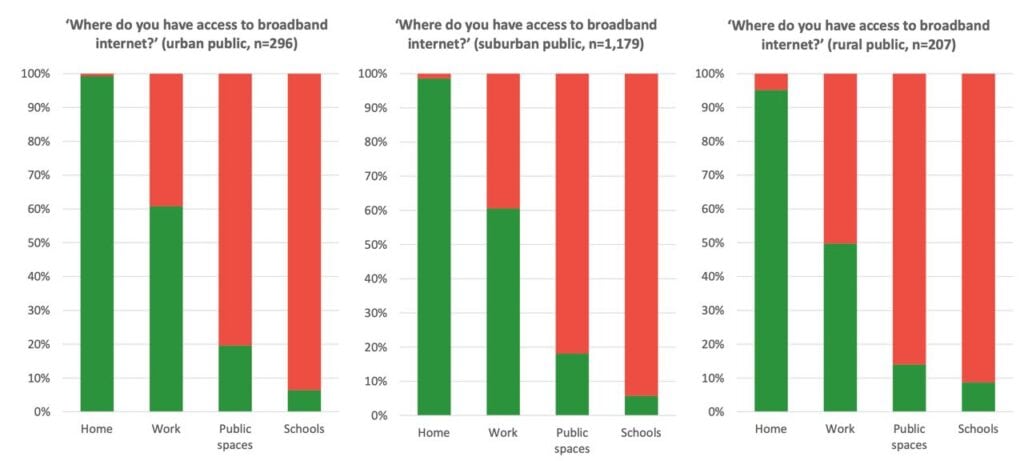

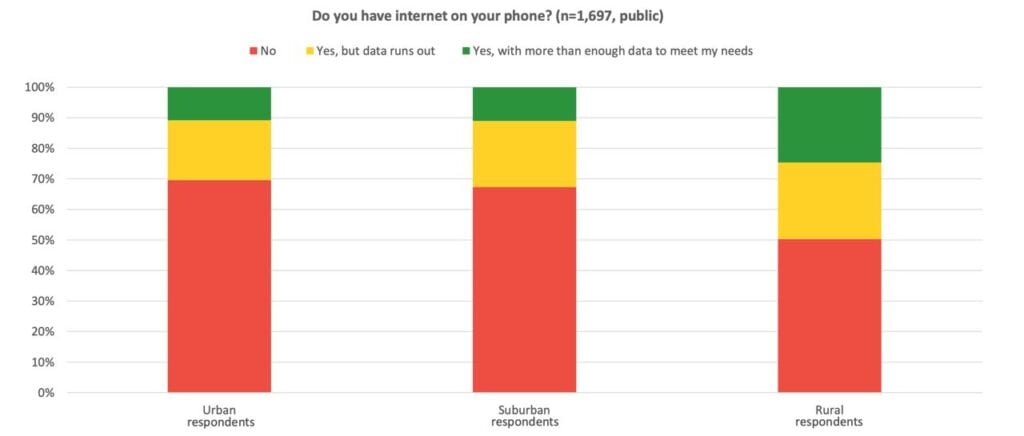

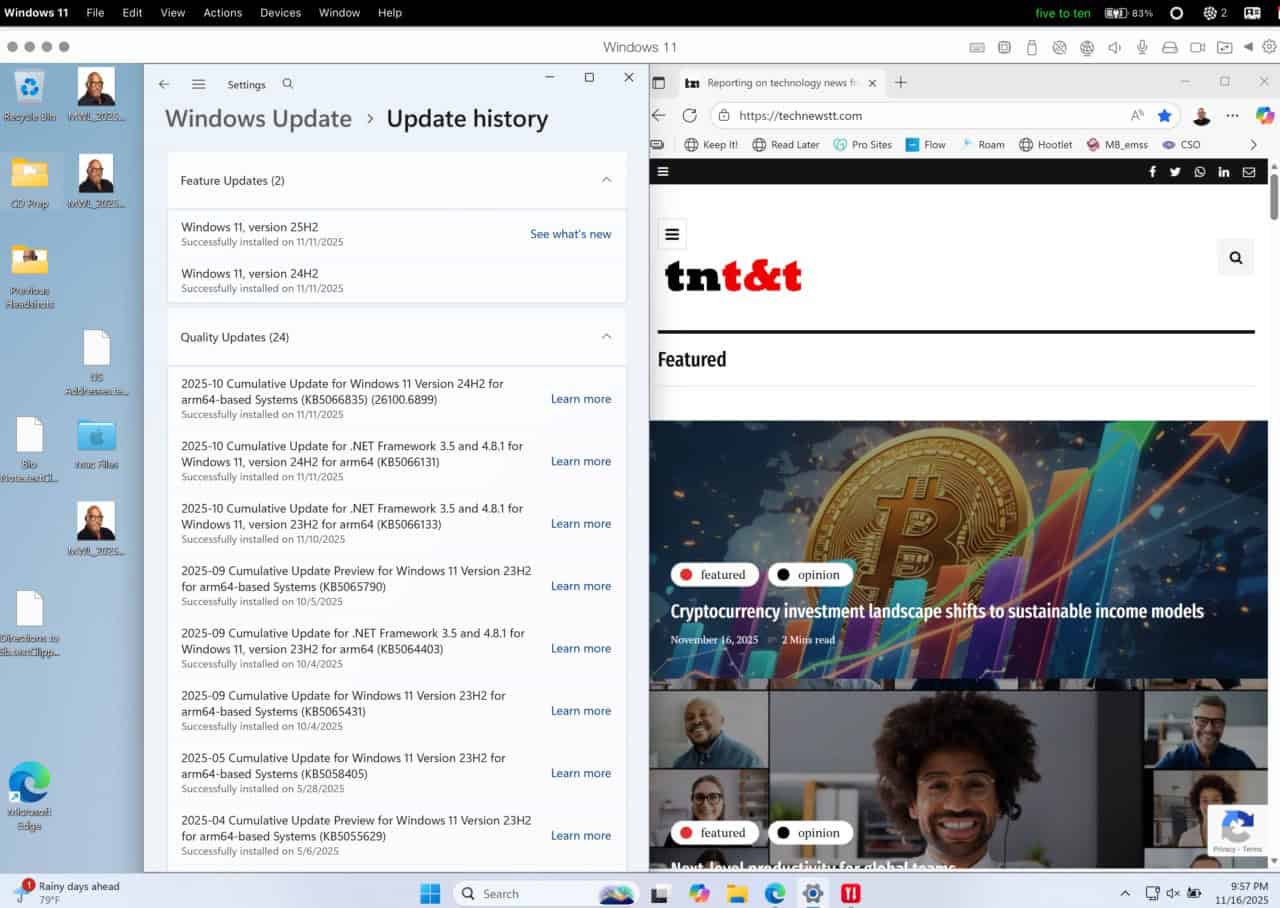

The report references a Digital Readiness Assessment (DRA) that the government worked on with the United Nations Development Programme.

The 2022 DRA report places TT at the midpoint of successful digital transformation – the “systematic” stage – in which a nation is said to be “Advancing in key areas of digital transformation based on identified priority areas.”

The BOLD document references anything in the DRA that paints a positive image of TT’s digital transformation, inclusive of charts and analytical frameworks.Were it not for the cribbing of the DRA graphics, the document might be confused for a repurposed tourist board document that leaned in particularly heavily on photos of butterflies.

The proliferation of that insect is oddly appropriate, because the strategy document flits from topic to topic without making any effort to pollinate any of it with real substance.

And some of the DRA’s conclusions are sketchy.

The UNDP finds, for instance, that there are “high levels of digital literacy” in this country, a factoid that runs counter to the MDT’s very public efforts to raise levels of digital literacy nationwide.

A thing either is, or it isn’t, and here, I’d argue that outside the air-conditioned offices where these reports get written, digital literacy is both rudimentary and task focused, quite some distance from the kind of confidently interpretive approach that’s needed to drive the ministry’s transformation aspirations.

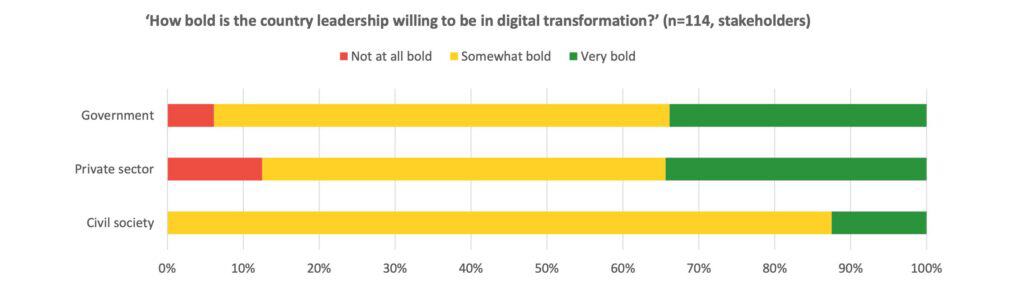

Here are some findings by the UNDP that BOLD does not trumpet.

Seventy per cent of 90 stakeholder respondents felt that the current digital economy offered few to no benefits for citizens.

While 91 of 115 respondents have made digital payments, only 21 of 107 have received a digital payment.

Just five of 63 respondents thought that new technology was being adopted quickly in the public sector.

Only 289 of 1,373 respondents characterised the government’s digital transformation as either bold or very bold.

In its fourth year, the MDT is trumpeting a national strategy that reads more like a manifesto than a real-world action plan.

There’s no effort to establish timelines, name any projects to achieve this hefty menu of goals, cite progress on existing projects, offer statistical learnings from its own internal evaluations of learned reality or even to suggest what all this ambitious word salad will cost the country.

That doesn’t stop the MDT from claiming successes for development projects it had absolutely nothing to do with, including projects by FILMCO (online streaming), the Central Bank (e-money) and private sector telecommunications companies (broadband connectivity).

The simple truth is that our government is where innovative ideas from local entrepreneurs go do die. I know this because I’ve spoken with these people.

There’s no mention of Parlour, the e-shop that TSTT was directed to create in 2022 that’s quietly disappeared.

The government’s role should be to facilitate change and innovation through effective governance and enabling legislation, but even by that measure, the last four years have been a catastrophic failure with no tangible indicators of useful change, given the determined nebulousness of the BOLD strategy document.

Minister Bacchus and his doddering entourage of aging, out-of-touch, boy’s club cronies have conspired to create a summary document out of two years’ worth of talking points that advances not a single tangible idea or proposal.

This document would be laughed out of a private sector boardroom and might not survive the scrutiny of a sno-kone vendor.

“How this affecting my shave ice, boss?

Even on a critical point like Open Data, an essential aspect of transparent, accountable modern governance that the government has paid lip service to for more than a decade, the document doesn’t seem clear on what the imperatives should be in pursuing greater access to identity scrubbed data sets that offer insights into the nation’s operational pulse to the wider public. Or even what the MDT thinks it is.

The DRA notes the lack of a strong Open Data dashboard, a rather polite way of noting that data provided by the government on its operations is scattered, sporadic and overwhelmingly incomplete.

Here again, an independent effort by UWI, data.tt, demonstrates the value of bringing even a few national datasets online.

Sadly, this isn’t the government’s first effort at digital transformation.

Of the “pioneering” fastforward project of 2003 and its stillborn successor, the BOLD document notes that, “The approach of government has been that of minimalistic and light-touch, acknowledging the maturity of the environment and the need to remain flexible, affording protection where required while facilitating open market activity.”

Those two decades of “light touch” have been hallmarked by incompetence, mishandled and stalled projects and a determined avoidance of public accountability.

Minister Bacchus has the unenviable task of following notable digital failures helmed by Kennedy Swaratsingh, Maxie Cuffie, and most recently Allyson West, who each dutifully offered a message of digital advancement in governance while presiding over pappyshow.

West has most recently been stalling on a work from home policy for two years now, probably hoping everyone will just forget the idea.

Trinidad and Tobago now has a ministry dedicated to digital transformation, but its first major policy statement offers nothing tangible, leverages no metrics for future projects and delivers all the gravitas of the delicate, clearly teflon coated butterflies that decorate its pages.

The BOLD document is not currently accessible online, but I’ve posted it here. View the 2021-2025 IDB country strategy (PDF) for TT’s digital transformation here.The DRA assessment for TT is available on the MDT’s website here.

Didn’t know that BOLD meant (Building Our Lives Digitally) … Your concerns about the lack of tangible progress, transparency, and effective governance in digital transformation are vital. I hope your insights encourage meaningful discussions that lead to real change in Trinidad and Tobago’s digital future.

[…] Trinidad and Tobago – The Ministry of Digital Transformation (MDT) published its National Digital Transformation Strategy for 2024 – 2027 and it is, in a word, an embarrassment… more […]