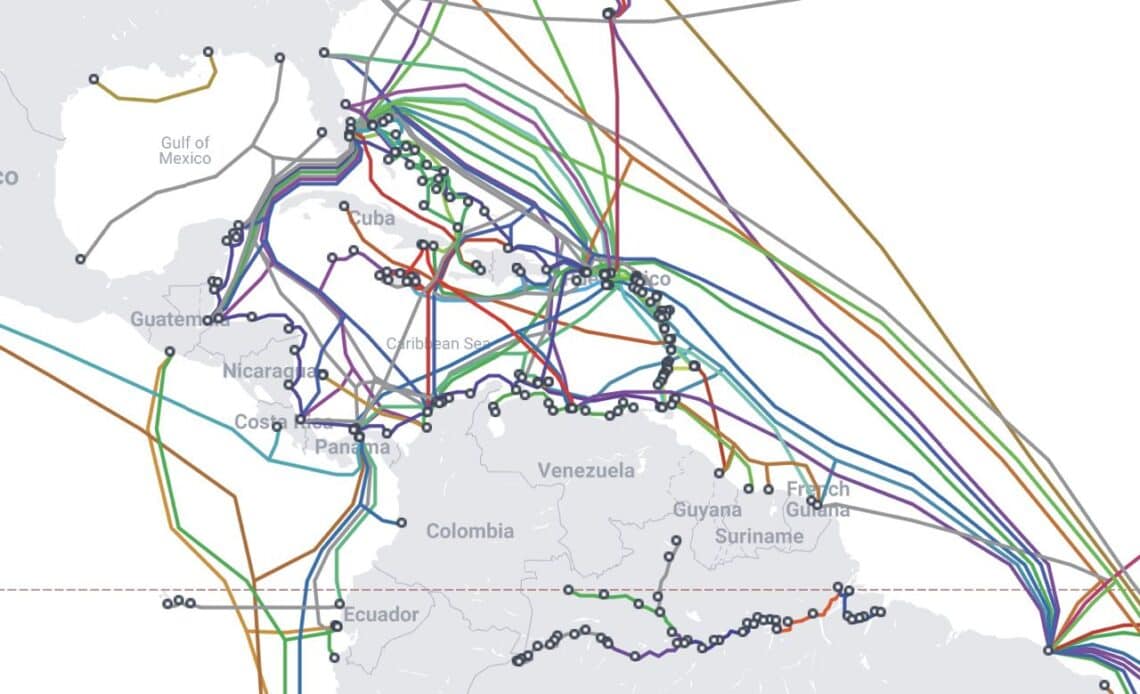

Above: A section of Telegeography’s subsea broadband connectivity map covering the Caribbean and Central America. The majority of broadband traffic is carried on these lines.

BitDepth#1492 for January 06, 2025

A new report, Gigabit Caribbean by Danish telecom consulting firm Strand Consult, was released in December 2024. It explores the challenges faced by operators and governments in driving investment in fixed and mobile networks in the Caribbean.

Strand surveyed most of the Caricom Caribbean, and sought perspectives from most large scale operators in those countries.

The report does not break out evaluations or statistics for individual nation states, but the aggregate findings reflect current concerns about how to finance next generation networks in the region.

The concept of a Gigabit Society was introduced by the European Commission in 2016 to describe a drive to very high-capacity networks that matched consumer shifts to internet based communications as well as the need to extend connectivity to rural and remote areas.

The strategy was considered an essential component for European digital transformation.

Strand suggests that a successful Gigabit Caribbean Society is one that implements 5G mobile broad band networks and fiber to the home (FTTH) download connections of at least 100 megabits per second (Mbps) by 2030.

In 2023, 5G networks accounted for just one per cent of all internet connections in the Caribbean.

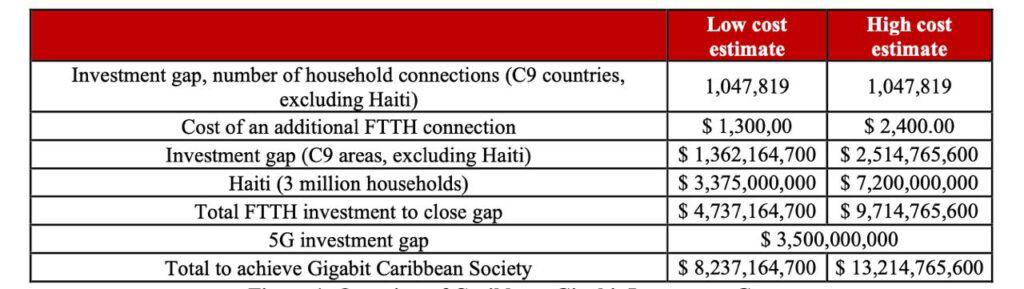

According to the report, 1.6 million Caribbean households have a FTTH connection and 553,681 households are passed by a fiber connection but don’t subscribe.

More than a million households have no fiber connection and the cost of connecting these households is estimated at US$2.5 billion.

The problematic state of Haiti’s telecommunications infrastructure makes FTTH there an even larger challenge, with the cost of bringing fiber to that country’s three million households estimated at US$7 billion.

That isn’t the only gap. Average revenue per user (ARPU) in Caribbean mobile broadband networks is around US$10 per month.

While mobile broadband is generally pervasive in the region where it is available, the cost of even a basic FTTH connection is US$50 per month.

The International Monetary Fund sets GDP per capita for the region at less than US$13,000 per person. Using a monthly budget for communications of two per cent of income as a yardstick, just US$21 is available for a FTTH connection.

Broadband connections priced to cover investment costs are likely to double that fee.

Operators surveyed for the report noted that further development is limited by the challenge of recovering capital expenditure.

There is no clear return on investment for high investment costs, particularly in rural areas that aren’t served by electricity (fiber installations usually run along electricity distribution towers).

Where is the development money to come from?

If operators cannot recover the costs of investment from end users, the conversation inevitably turns to services that make disproportionate use of established networks as sources of revenue.

Globally, 80 per cent of internet traffic is video streaming entertainment. Efforts at persuading the providers of these services, as well as other services that are implemented by free riders on existing broadband connections, such as voice and video calls on messaging services, have failed in the Caribbean.

The report references the development of South Korea from an agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse and its leveraging of robust broadband connectivity as a backbone of that development, beginning in 1994.

South Korea brought half of its population online by 2002 and began rolling out 100 megabit service in 2006.

Driven by this online capacity, two native services platforms, Kakao and Naver, became a robust presence in the country.

The country’s ubiquitous connectivity provided a basis for a robust cultural economy that includes K-Pop groups and Korean dramas, both of which have been successfully exported to global audiences.

South Korea is considering the European Union’s Digital Markets Act, as a model for extracting revenue from streaming services.

The Korean Free Ride Prevention act attempted to bring market-based negotiation between broadband providers and the largest generators of network traffic.

In South Korea, the largest network traffic, 41 per cent, is generated by Google, Netflix, Naver, Meta and Kakao.

The contretemps was eventually settled with a backroom agreement in September 2023, but it’s a country-specific case, since Netflix leans so heavily on South Korean content for its services.

Cork ball players like Meta have simply refused to enter negotiations and even after establishing an interconnection agreement with Germany’s Deutsche Telekom, simply stopped paying and the agreement collapsed in September 2024.

SK Broadband and Netflix have jousted in court since 2020 over infrastructure improvements totalling US$40 million incurred by the internet provider after Netflix demand jumped by more than 26 per cent in the country.

Conversations about the free ride that over the top (OTP) players have enjoyed in the Caribbean for more than a decade continue, but the response from streamers and services remains unsatisfactory.

Price competition in the best wired countries in the region is a disincentive for further investment in telecommunications infrastructure.

Most remote areas eventually get service either through Universal Service Fund projects like those sporadically implemented in TT or through breakthrough technologies like Starlink’s satellite connections.

The status quo is a price-driven stalemate between sunk costs and customer spending reluctance that’s unlikely to be broken by anything short of new competitor investment in more advanced technologies.

So Over the Top players get a free ride, while Telcos are straddled by national boundaries and local regulations.

Governments, naturally, have a local focus while the OTP players operate globally, un-impeded by local regulations.

Is there a lesson here for more regulation or deregulation in a “free” market?

I think the issue is, Telcos are viewed as part of necessary infrastructure, like electricity, roads, water. .. not YouTube or FaceBook.

Granny, at the end of nowhere lane should have electricity, not dependent on the investment case that requires 2 lamppost and wire from the main road to be deployed.

Hard choices so what do we do?

If there was a Telco (global market rep?) with the reach and size of Google or Meta, I can assure you the OTP players would have no choice but to pay to play.

At least the costly expansions that require capital investment in equipment for Tera-Bit pipes (coming soon) could be offset by paying OTP players.

..at least so, in Wayne’s World.

\Wayne

[…] Caribbean – A new report, Gigabit Caribbean by Danish telecom consulting firm Strand Consult, was released in December 2024. It explores the challenges faced by operators and governments in driving investment in fixed and mobile networks in the Caribbean… more […]