Above: Adobe’s headquarters in Silicon Valley Photo by wolterke/DepositPhotos

BitDepth#1463 for January 17, 2024

Adobe, the market leader in delivering software for designers, photographers and creators across a range of fields found itself in hot water with its customers when the wording of its new terms of service in the revised end user licensing agreement (EULA) struck a discordant note.

The EULA had apparently been changed since February, but this is a lengthy legal document that users skim idly before clicking acceptance, having read not a single word. It took months before anyone noticed a significant change.

In a dramatic rewording of its handling of customer content stored on its servers, Adobe seemed to claim a sublicense for the creative work uploaded to its servers. Speculation immediately began that it would use that work to train its image generation AI, Firefly.

As part of its now exclusively cloud-based, rental software business, Adobe offers service sweeteners in its plans which allow customers to store data for collaborative work and to create portfolio websites.

The company has since announced a reworking of the offending EULA to remove the inference of sub-licensing, but not before users past and present weighed in.

It didn’t help that this revelation came on the heels of a conversation that Adobe’s CEO Shantanu Narayen had with The Verge in which he rather proudly declared, “I think generative AI is going to attract a whole new set of people who previously perhaps didn’t invest the time and energy into using the tools to be able to tell that story.”

“So, I think it’s going to be tremendously additive in terms of the number of people who now say, “Wow, it has further democratised the ability for us to tell that story.”

To be fair, Mr Narayan is hardly the only person to be shoving rather startling amounts of money behind the idea that photographers are now largely disposable parts of an ever more democratised image making process.

Once stock photography sites began including AI alteration and creation tools in their offerings, it was clear that even that wildly devalued photographic revenue stream was also going to dry up at the source.

There’s a point when a tool takes over the process of creation and becomes an engine of image making itself and Adobe’s new Generative Fill feature has already jumped that shark quite decisively.

A week ago, Adobe posted a statement on its company blog to clarify its position and unveiled new, more clearly creator-friendly wording for its EULA, noting that, “We’ve never trained generative AI on customer content, taken ownership of a customer’s work, or allowed access to customer content beyond legal requirements. Nor were we considering any of those practices as part of the recent Terms of Use update.”

That sounds good, but it presumes that Adobe can draw on a vast wellspring of customer goodwill to tide it over an incident that’s shaken customer trust.

I’ve been an Adobe customer since 1995, when I bought my first copy of Photoshop, version 3, an upgrade from the limited edition copy that shipped with a scanner.

Technically I’m still a customer, because I have an active perpetual license for version 13 of that software (CS6), though the company hasn’t gotten a cent from me since it switched to renting its software by the month.

I’d been using the image editor since 1990 with version 1.3 and was immediately smitten with its capabilities compared to the mechanics of the darkroom.

It’s not out of line to say that early version of the software marked the point at which I simply stopped working at analog photography and began building the boat that I’d use to navigate to a next-generation digital workflow.

So, y’know, Adobe’s Photoshop quite literally changed my life.

That’s a lot of emotional investment right there, but give the company this, it has worked industriously to strip every iota of my sentiment away.

Since opening that first box (yes, they came in big boxes with stacks of floppy disks and book sized manuals), I’ve owned versions 4, 5, CS, CS2, CS3, CS5 and CS6.

When Lightroom was introduced, I was a user from the public beta, advancing through every version of that software until perpetual licenses ended with version 6.

To upgrade in the days of dial-up, I’d finagle my way onto the backbone connection at WOW.net to get a connection that made the hefty download possible.

Then, somewhere around CS3, Adobe simply decided they didn’t want my money. I couldn’t pay for the software anymore because of some bizarre geofencing arrangement.

So I’d send cash to a trusted friend in the US to buy the required serial number.

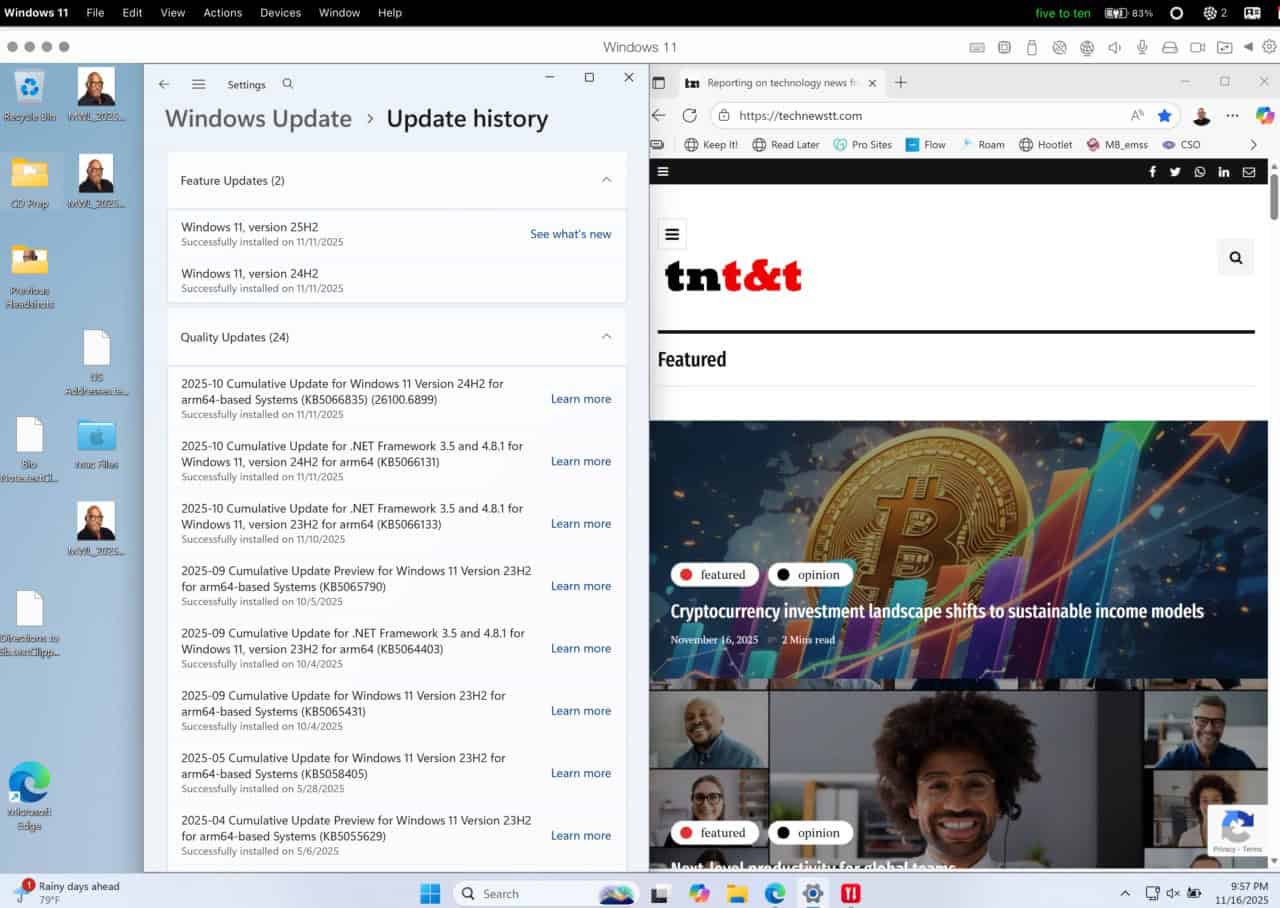

The activation servers for Adobe’s CS, CS2 and CS3 products were shut down between 2013 and 2017. In May last year, Adobe stopped its customer support from deactivating perpetual licenses for customers.

Those licenses allowed you two installations (expected to be a laptop and desktop) then locked you out of the software.

An end user can deactivate and reactivate the license to move to a new computer, but that doesn’t work if you’ve lost your computer to either a hard drive crash or theft.

I recently had to move my sole remaining activation to another computer, but it didn’t work as advertised and I had to jump through some unnerving hoops to do an offline activation on a computer that was actually connected to the internet.

Customer support is now stony on this and other related historical matters, directing users in distress to purchase an updated rental copy of the software.

Rummage around for long enough on Adobe’s forums and you can find a link that takes you to your legacy installers for the software you are supposed to be able to use perpetually and maybe find an Adobe employee willing to do a behind the scenes compassionate account activation reset for you.

But that’s increasingly unlikely. The overwhelming official vibe is that you’re an annoyance who won’t buy the great new stuff.

Using old Adobe software also means maintaining a legacy computer that can run it. Not an easy thing in itself.

The restrictions on activation resets suggest some new meaning of the word perpetual that I can’t find, but I’m obviously not referencing the dictionary that Adobe uses.

I don’t entirely object to the subscription model of software access through monthly rental. I have a subscription to Microsoft Office and at least one shareware app because they both offer a significant and specific use case for both in my work.

The young photographers on a WhatsApp group I’m part of sing the praises of new Photoshop. I’m sure they are right. But CS6 and most of its predecessors are the best kind of tool for me, an extension of my good right hand.

Photoshop is a sledgehammer that I wield with great fluency in my work. When the handle (computer) wears out, I put the sledge on a replacement stock.

I don’t need the new diamond-tempered, titanium reinforced new model, thank you. Just let me use my trusty, faithful sledgehammer. In perpetuity.