Above: Microsoft’s new Surface PCs in the CoPilot+ line.

BitDepth#1460 for May 27, 2024

On May 20, a week ago, Microsoft announced its new line of CoPilot PCs led by new versions of its Surface computers.

Microsoft’s Surface computers are not just a product, they’re the company’s concept machines, luxury devices that are supposed to inspire design cues among the many partners that build computers to run its software.

The biggest cue Microsoft offered in these new computers was an apparent commitment to ARM based processors from Qualcomm, specifically its new SnapDragon X CPU, Hexagon NPU and Adreno GPU.

ARM or Advanced RISC Machines, is a company that has been focused on low power draw, high performance instruction set architectures and computing core designs since 1985.

Microsoft is making lots of noise about the AI capabilities of its new Surface computers and the system design it hopes will be taken up by its hardware manufacturing partners.

Acer, ASUS, Dell, HP, Lenovo and Samsung have announced a cautious release of new computers using the new chip designs that run Windows on ARM, which is now a product in wide release.

The new computers are also a signal from Microsoft that it is willing to support other processors for mainstream use. Since the company was founded, its OS and apps have been almost exclusively coded for chips manufactured by Intel.

But it’s not the first time that Microsoft has looked to another manufacturer of CPUs for a product. In 2005, the company launched its new Xbox line of gaming consoles with the PowerPC chip developed by Apple, Motorola and IBM which had previously been used by Apple as its second generation processors between 1994 and 2006.

In 2012, Microsoft took its first stab at an ARM based Surface computer, the ill-fated Surface RT which ran a severely pruned version of Windows on underpowered hardware (The company would eventually write off US$900 million after it failed).

Intel’s chips use what’s known as CISC, or complex instruction set computing. Chipsets based on ARM computing designs are described as RISC, or reduced instruction set computing.

The differences between the two, even in simplified form, are deeply technical, but the way the two chip architectures process the instructions that are written into code is different.

Those differences have blurred over time, but RISC chips offer a more elegant way of executing code on hardware delivering more performance while drawing less power.

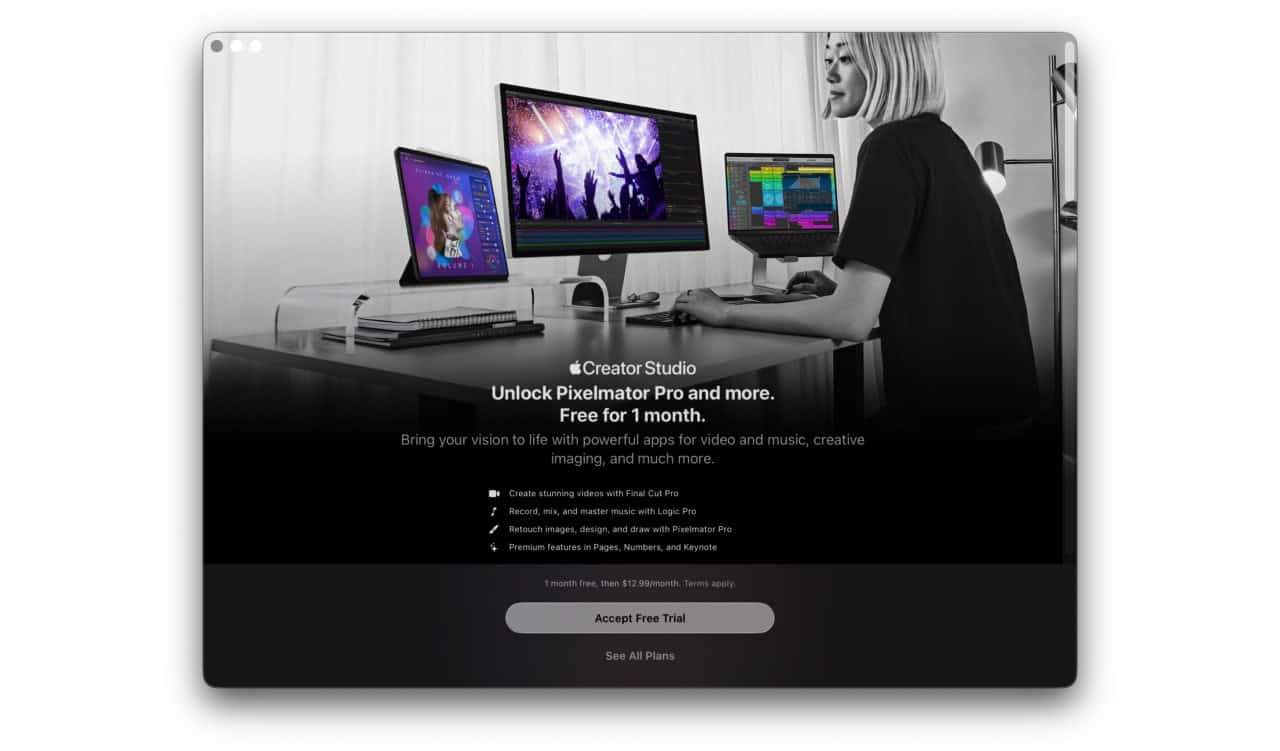

It isn’t surprising then for Microsoft to openly compare its new Surface systems with Apple’s popular M3 MacBook Air.

“[The ARM Surface computers] are up to 20x more powerful and up to 100x as efficient for running AI workloads and deliver industry-leading AI acceleration,” wrote Yusuf Mehdi, Microsoft’s Consumer Chief Marketing Officer on the company’s announcement blog.

“They outperform Apple’s MacBook Air 15 inch by up to 58% in sustained multithreaded performance, while delivering all-day battery life.”

So where do these new Windows computers fit into Microsoft’s PC strategy?

They reaffirm the company’s commitment to Windows everywhere, crafting a uniform and predictable interface for its core operating system across devices.

The new iPad Pros may be fast and look like a Surface computer, but iOS is a mobile operating system without the nuances of a desktop OS.

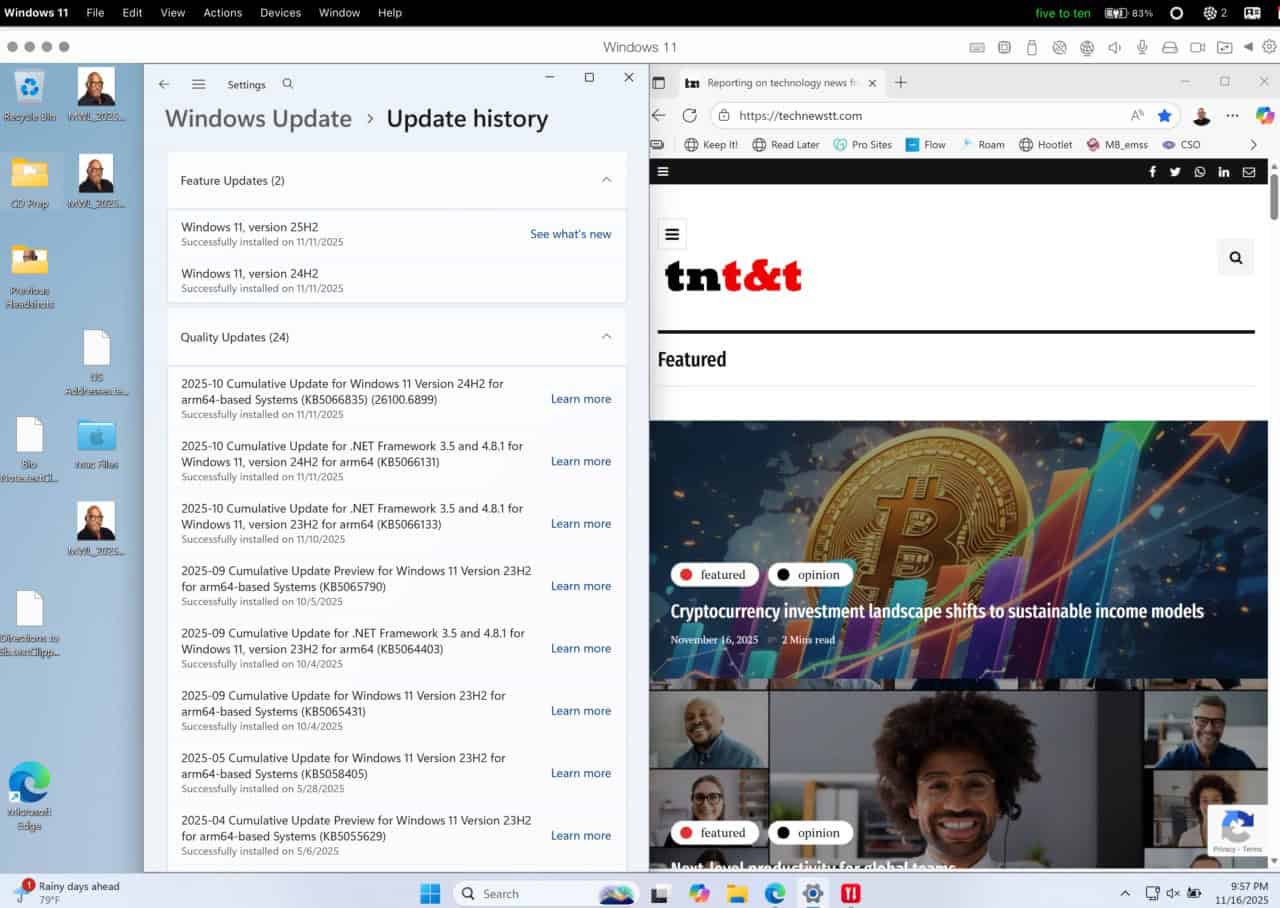

As it turns out, I’ve been having an interesting experience with Windows on ARM over the last month or so after installing the OS on an M1 Mac running Parallels, an emulation tool that translates instructions between the Windows environment and the Mac with reasonable efficiency.

Last month, I bought a Windows 11 Pro license after yet another reminder to activate in the emulator environment.

It’s a bit crazy that I’m running a version of Windows optimised for ARM computers on an ARM computer, but in emulation mode. Does this make this version of Windows faster in any way?

The only major problem that I’ve encountered so far in that environment is likely to be replicated in any current Windows 11 installation. Microsoft has tightened up permissions, and it makes installing, far less running really old Windows software a sketchy proposition.

Windows 11 on ARM improves emulation for apps coded for Intel by adding support for 64-bit emulation. You can apparently also run Android apps in this environment, but I couldn’t figure out how.

I ran two InstallShield installers for graphics software that worked without incident on earlier Windows versions running under emulation.

Admittedly, these apps are more than two decades old, but it was cool to see them running again on any computer system at all.

One installed and ran without incident, the other threw a security exception that resisted very bit of advice the internet had to offer.

This emulated instance of Windows runs without glitches, even briskly at times, but as with any virtualised hardware environment, fast drives and copious RAM are always a distinct asset.

I’ve set the emulation model in Parallels to productivity, which balances use of the host environment with the virtualisation of Windows. There’s a gaming setting that demands more of the resources of the host computer.

Microsoft promises an efficient emulation layer for software expecting an Intel chip on its new CoPilot+ PCs, but they are unlikely to satisfy users looking for big iron performance.

Simple, idle time games run without issues. Angry Birds 2 and Asphalt 8, neither of which are particularly demanding of hardware resources, ran smoothly, though Asphalt 9 required an XBox Live account, which I don’t have.

For users who don’t require next level hardware responsiveness, the OS, under emulation, is largely problem free.

With these new systems, Microsoft is acknowledging that it markets to two distinct classes of users, those who do routine work and prefer responsive machines with hours of battery life and users who want all the CPU clock cycles, GPU performance and memory bandwidth they can find and are willing to throw money and large fans at that goal.

These new ARM PCs are aimed squarely at the former market (with Intel and AMD versions to come, so bets are hedged), but they are also a litmus test of both the market’s willingness to buy chips at some remove from the familiar comforts of Intel.

It will also demand developer willingness to create native apps to run on what is, despite the seamlessness of the new systems, at the very least an extension, if not a branching of the Windows platform.

For the company, it’s a restatement of purpose for its in-house line of Surface computers, which peaked in 2022. Microsoft stopped reporting Surface sales specifically that year, rolling its numbers into “Device Sales.”

Surface computers have never commanded more than an average of just over two per cent of the computer market over the twelve years that they have been sold. Microsoft may not necessarily want to change that, but they do want the CoPilot+ PC concept to soar.