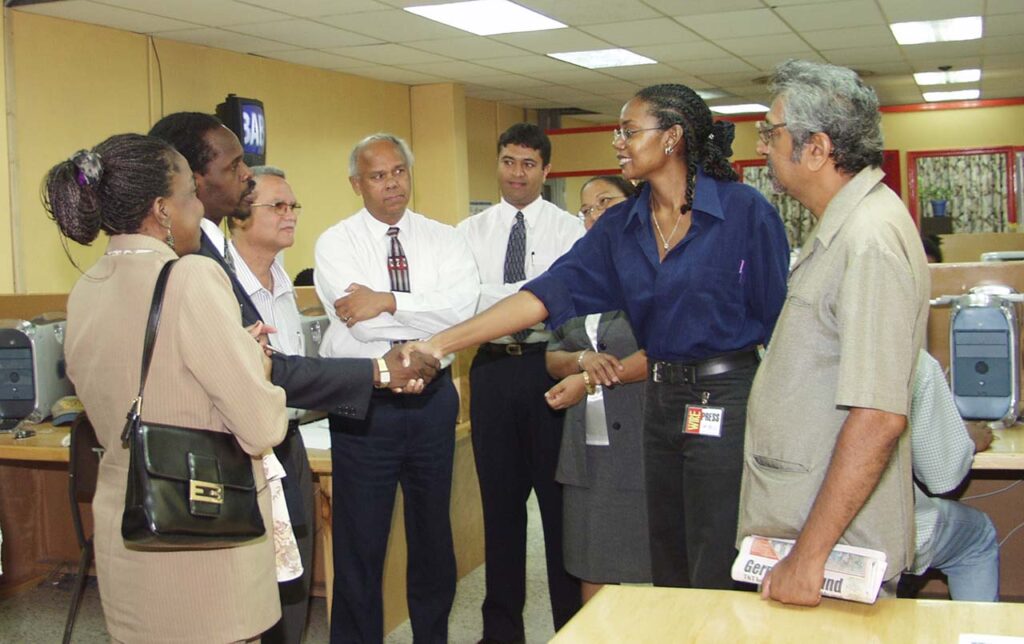

Above: Tricia Lee distributes copies of The Wire on the launch day, September 10, 2001. Photo by Mark Lyndersay

Story start

This is the story of The Wire, a newspaper published between 2001 and 2003 by the Trinidad Publishing Company (TPC), publisher of the T&T Guardian and now operating as GML. I served the paper from months before the first publication and oversaw its closure as its Operations Manager.

This is a long account, likely to only be of interest to media professionals and those who worked on the paper, but it is also a record of what may be the last attempt to produce a daily print publication in Trinidad and Tobago in the twenty-first century.

The economics of print production of news is unlikely to finance another effort at creating a general news print publication.

I had joined TPC as a fuzzily defined consultant in November 1998 after Lennox Grant had returned to the paper as its Editor-in-Chief.

Grant had served as the paper’s News Editor, where I’d met and worked with him at the end of 1989. Back then, I was the paper’s first Picture Editor and we worked closely, though at first somewhat tensely on the paper’s journalistic approach.

By 2001, the team that Grant had assembled had hit a wall. Several former Trinidad Express people had joined the Guardian, raising tensions, with no commensurate rise in circulation.

It wasn’t just a matter of competitive journalism, which I thought we were doing rather well.

The paper had been through perceptual hell with the walkout of much of its senior editorial team, led by Managing Director, Alwin Chow and Editor-in-Chief Jones P Madeira.

I’d sit in on marketing focus groups, listening to people who wouldn’t consider buying the paper although they couldn’t quite explain why.

At least part of the problem was a press conference hosted by the paper’s owner, ANSA McAL, to announce Owen Baptiste as the replacement EIC on an acting basis.

I’ve never forgotten the visual of the late Anthony Sabga slamming his hand on the desk to emphasise his belief that anyone who wanted to leave could go.

It was a resonant moment of bad public relations that would echo down through the paper’s existence from that day forward.

In 1999, the Guardian won six high-profile media awards in the annual journalism competition. I got one for Feature Photography, along with columnist Ira Mathur, Business Editor Anthony Wilson, Rory Rostant and Kevan Gibbs, who led the paper’s daily front page design effort.

By 2001, the conversation had turned to other ways to increase the paper’s youth demographic.

TPC had published a tabloid paper for decades, the Evening News, an afternoon paper that featured court reporting and entertainment news, targeting commuters on their way home from work.

After the disruption of the coup attempt by the Jamaat al Muslimeen, when the Guardian’s press room was shot at with automatic weapons, the faltering paper was taken off the publishing schedule and would never return.

Why The Wire?

The Guardian had redesigned its size and page layout to what was then described as a ‘broadloid.’ The page size was down from the hefty broadsheet it had been for most of its life to a slightly smaller product that emphasised attractive design.

Denise Baptiste, an excellent conceptual designer and intuitive page layout artist, had joined TPC from the Express and worked with Gibbs on the redesign of the paper.

But it was still saddled with its reputation. The serious, contemplative positioning of the paper, ‘The Guardian of Democracy,’ resonated well with older readers, but didn’t seem to be reaching a younger demographic.

The TPC Board of Directors wrestled with the idea of transforming The Guardian into a tabloid paper for years.

Designer Kevan Gibbs recalls being called into Lenny Grant’s office to design a prototype of a tabloid Guardian for the Board of Directors at least a year before a second paper was discussed.

Even at that early stage, Gibbs argued that the company should consider a new evening paper targeting commuter traffic congregating at City Gate and at taxi stands.

Peter Gomez, then Company Secretary, pointed out to me in a recent exchange of emails that the Barbados Advocate, also owned by ANSA McAl, had switched from broadsheet to tabloid around that time and there had been no change in sales figures for that paper.

Anthony Sabga, chairman of the board, was also adamant that the paper should remain a broadsheet.

The pros and cons would eventually be resolved with a pilot project, a new Guardian produced tabloid as a way to experiment with content as well as size.

The new tabloid was meant to achieve two things, attract younger readers to a TPC publication and experiment with a full tabloid production environment and press workflow.

I attended a series of meetings that were intended to shape the idea and define it.

It soon became apparent that I was in the company of people who were very good at continuing the production process of The Guardian, but had never created a journalism product from scratch.

In all fairness, neither had I, though I’d worked with Keith Smith on The Sun, the afternoon paper that the Express produced for half a decade as competition to the Evening News.

“Stories should be short, but not too short.”

“Pictures should be big, but not too big.”

After several weeks of this, I stepped away from these circular conversations and wrote a four page document for what was then being considered to be either The Star or The Sun, offering a printed document (PDF of the original proposal text) to the Managing Director of TPC, Grenfell Kissoon.

Within the week, I was summoned to a meeting with Kissoon and Martin Daly, who was then the Chairman of the TPC Board.

I was told to work with Andy Johnson, the Guardian’s editor, had been chosen to lead the editorial team of the new publication.

Kevan Gibbs was busy planning his big beach party, Great Fete, in Tobago and after doing some preliminary work on the design prototype, left to manage the event.

Andy Johnson went on leave. He picks up the story.

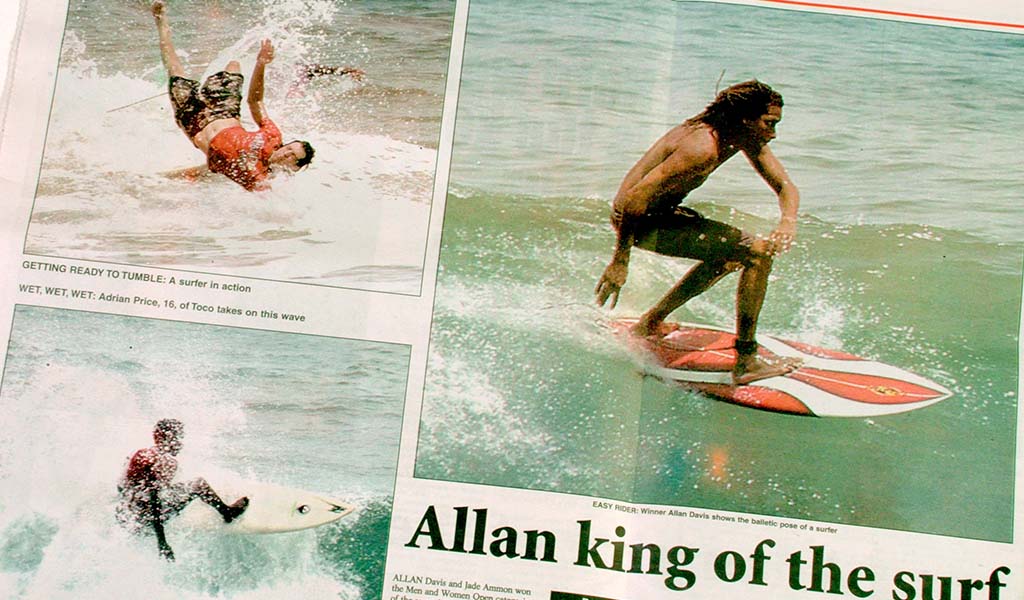

Photo by Mark Lyndersay, November 10, 2001

“So I took leave because I was due for leave, because I always put in my leave at the appointed time to do so, which is early up in the year, and I always stick to that.”

“I always remember Kissoon telling me, when we were up at TBC (Trinidad Broadcasting Company) that when it came to leave I was about the most disciplined of the managerial team.”

“I was assisting him in trying to find an Editor for the (tabloid) paper. That was my major role.”

“When I came back from leave, having drawn a blank on that account, this is when he put it to me that perhaps I should consider taking the job myself.”

“I never fully accepted that this was what I wanted to do, but went along with it, because of the relationship I had with him.”

“The person I had in mind for the position was the late John Myers, who was my editor in my earliest days in journalism, at the Evening News.”

“Compton Delph was the editor, but Myers was the man in charge so to speak. He was then editor at the Bomb, working with Sat Maharaj. My sense is that he didn’t want to come back to the Guardian.”

“As Editor of the Guardian I attended meetings of the Board of Directors, along with Grant. And the discussions around that table suggested a kind of paper that would be more tabloid than the Express and News were at the time.”

“The idea was that the Wire would go head to head with them, more on the British style tabloid format. Martin Daly, as Chairman of the Board, felt this was the way to go, but Kissoon had some more conservative views.”

“He wasn’t quite ready to ‘go there,’ so to speak. So that after Board meetings, he would tell me on occasion, not to imbibe too much of what Daly was proposing.”

“So when I did take the plunge, what I had in mind, was to find the kinds of people who would create the kind of excitement with their writing and reporting, that I envisaged would meet the expectations of the ultimate decision-makers.”

“I tried to “hear” where Daly was coming from, while yet being mindful of Kissoon’s conservatism.”

Whither The Wire?

An entire floor of the adjoining press building was identified as a site for the publication’s newsroom.

The large terrazzo finished space was a floor above the massive press room below and had earlier been home to the sprawling production department, tons of machinery for exposing large negatives and platemaking that digital technology had made obsolete.

By this time, I had been granted a provisional status as operations manager of the new paper, now operating under the name The Wire, following on a suggestion by Johnson, who recalled that ‘to get a wire’ was an old term to get urgent information on a special channel, a dated reference to telegraph communications that seemed hip again in the digital age.

During the month of August 2001, infrastructure was put into place. I discovered that a production worker was also a skilled woodworker and gave him rough plans for a desk system that I drew for him rather crudely using the ‘draw’ module in AppleWorks.

Thankfully he was able to make sense of it and created a sample that passed muster with the TPC executive, going immediately into full production.

A kitchenette was shaped in the middle of the floor, a cashier’s cage built against a wall and plumbing laid in for three toilets upstairs of the newsroom space.

For the whole of the time that the paper was in operation, I’d look up at least once a day to the celotex drop ceiling above my desk where the waste pipes from those hastily put together facilities ran.

In parallel with the infrastructure, there were hardware and design issues to manage, a matter complicated by Gibbs’ Great Fete responsibilities.

I worked with Denise Baptiste on the new paper’s logo, purchasing the distinctive font that emerged as the successful logo design choice.

“The Wire was given a fighting chance,” Peter Gomez recalls.

“It wasn’t considered the stepchild of the Guardian. It was outfitted with new equipment and some of the best staff of the Guardian (who were) willing to start with fledgling newspaper. Newsprint was purchased; the press was adjusted to allow for more colour and tabloid publishing.”

The Guardian’s IT department uncrated new iMacs in a variety of colours, ethernet cabling was threaded through the drop ceiling and I got the final word on a vibrant curry yellow for the walls, accented by a searing red for the space, picking up the vivid colours that Baptiste had specified for the logo following Kevan Gibbs’ designs.

A month before first printing, the desks were being assembled in the space, the wood still rich with the outgassing of fresh varnish, a massive UPS was rolled into my office and a small television was strapped onto a wall arm overseeing the newsroom space where it would soon serve as an oracle of warning.

“The Wire shared the NewsEdit database server from the Guardian (you probably just had your own publication code, so stories wouldn’t accidentally be pulled to the Guardian by accident) and used our existing servers to store your pages,” former Guardian IT administrator Michael Tikasingh wrote in response about the technology arrangements.

“I’m pretty certain we just dropped a switch in that area and then strung a single ethernet cable from that back to the information systems department. As a network issue, I don’t think it was a particularly complicated arrangement.”

“One of the main problems, of course, was that staff from all publications kept pilfering fonts from every gutter they could find, so QuarkXpress would crash continually.”

l’d really wanted to oversee the photographic department, and chose Andrea De Silva as the senior photographer, one of a few editorial staff that I was responsible for hiring, along with the small photographic department.

Except for Andrea, I wouldn’t get any of the photographers I wanted to hire, but coaching a new breed of image professionals (Karla Ramoo, Curtis Chase and Keith Matthews) turned out fine.

The paper would be entirely digital right from the start, connected for text to NewsEdit, with pages produced on Quark XPress. The images would be digital files from end to end.

I chose Olympus E-10 digital cameras for their mix of heft, overall features and most importantly in 2001, price (around US$2000). The cameras shot a four-megapixel file, had poor low-light capabilities above 400 ISO, and didn’t have interchangeable lenses.

You could screw on wide angle and telephoto adapters to the front of the F2-2.4, 35-140mm lens it shipped with and I asked for a couple of those adapters as well. They were hefty, unfortunately, and didn’t get much use.

I can still recall the lunatic joy of unboxing all the bits and pieces of this all-digital photographic department, the first to operate in Trinidad and Tobago. It was a riot of cardboard and shrinkwrap that I’ve never experienced since.

On that high of borrowed bliss (none of the cameras would ever be used by me), we come to the story of the Ungers.

Inward Unger

A couple of weeks before the paper would go to press, I was introduced to the husband and wife team of Mike and Noorah Unger, newspaper consultants from Fleet Street who had been hired by TPC to revitalise the Guardian’s sales positioning.

At this point, I would have been in drifts of sawdust with a vineyard of power and network cabling dangling overhead. I did not see what was to come.

In planning this account of the creation of The Wire, I was mightily tempted to just leave them out, but this would be an incomplete report without an assessment of their role.

Despite a lingering resentment whenever I think of their part in the creation of The Wire, they played a significant role in sharpening the news approach of the paper and their advice, on balance, offered real value to the team that produced the paper daily.

But they were also skilled at eviscerating any attempt at effective harmony among the management team of the paper.

Kevan Gibbs, who was supposed to be the design chief on the new paper recalls: “My personal disappointment came mere weeks before the launch of the paper when two foreigners from the UK were imported to work on bringing the final product to reality.”

“A reality which in my view resulted in them just taking what I had already created in the trenches of the Guardian design desk, adding a few light colour changes and presenting it to the board and management as their own, and then being publicly credited for the work and amazingly short turnaround time.”

“What I saw as the disrespect by the two UK foreigners to the local staff and the bad aftertaste I had towards them, made me gravitate back to the Guardian and after a few months away from the Trinidad Publishing Company altogether.”

“Funny enough, I would return a few years later (2007) to help with a new redesign project, which resulted in the Guardian finally transforming itself into a tabloid in 2008.”

“When the Ungers came, Kissoon stunned me one day, by telling me that I should, ‘manage’ them,” Andy Johnson said.

“He felt that, from my understanding of his position, they were being given too much leeway to do what they wished, from Head Office.”

“I soon came to realise that in their minds, they were running the show, and I was there for ‘reference.’”

“I remember one day telling one of the subeditors something about the placement of some item or the other, on a page, and the sub told me that this is how Noorah wanted it. I think it included the use of the term ‘Mum‚’ instead of Mom, for mother.”

“On another day, I had been out of the office for an hour or two, and Mike had an issue with that. I came back when I thought it would be crunch time, to put in the time required to get the paper to bed.”

“Mike shoved me into my office, scolding me because he was trying to find me and I wasn’t around at the time. He told me I shouldn’t take the job if I didn’t want to assume the responsibilities associated with it.”

“I wouldn’t tell you what I thought of it, but I took that to heart. I asked myself, Who’s in charge here? I had also by then become angry with myself for having taken this position, which meant that I had to give up my Sundays, and I resented it deeply.”

“And then, just like that, I got a call from someone asking me whether I would consider taking a job as Head of News and Current Affairs, at Power 102fm, which was then struggling to fight off the haemorrhage of staff, with the coming on air, of i95.5fm. I jumped at it. All of this was inside three months.”

Two things happened immediately after Andy Johnson’s sudden, shocking departure a few weeks into the paper’s first publication.

News Editor Irene Medina was invited to take over the editor’s chair and Mike Unger came to my office, clearly bristling about having to ask whether I would write the editorials now that Johnson was gone.

The Wire was more important to me than my distaste of him, and I agreed, undertaking the writing of four of the paper’s five daily editorials from that day until the paper’s closure.

The story of the Ungers at TPC would come to a stunning end four months later after the couple were retasked to their original mission, to revamp the Guardian, ending the months of cohabiting the newsroom space with them.

I’d come to believe that when they arrived, they saw the raw clay of The Wire and the decades of institutional resistance at the Guardian and decided to make their mark in a more malleable project.

On the very first day of work in January 2002, I took a panicked call from Noorah early in the morning.

She was looking for pictures for pages and there was nobody at the Guardian. Her husband was apparently quite upset. I tasked the duty image librarian/scanning tech with providing the requested images and pressed on with my Unger-free day.

I’d learn, from scattered stories later that week, that at some point, Mike Unger had simply left the office, his wife and his suitcase, and boarded a plane back to the UK.

Noorah Unger stuck around for a few months to do the work they had been contracted for, but eventually decided to leave as well.

On her last day, I came to her office, asked if she might have a moment and said only this: “I’m sorry about happened with your husband. I wish you well, and I hope you find happiness.”

Then, I got up and left. I hadn’t come for a conversation.

I later heard from Andrea De Silva, who was friendly with her, that Noorah mentioned during their goodbyes that, “Mark might be still very bitter.”

That was fair comment.

September 10, 2001

The first official day of work at The Wire was September 09, 2001 a Sunday, although work on stories and building cohesion and approach in the newsroom had begun more than three weeks earlier.

Planned as an urban, youth-focused paper, The Wire would publish Monday to Friday.

September 10, the first day of The Wire’s publication was also the first day for a marketing effort by Anthony Sabga III, who was working on a range of promotions for both papers and particularly relished the launch of the paper, which took the form of a music tent on the Brian Lara Promenade populated by Carib girls in Wire t-shirts and really tight cycle shorts handing out free copies of the paper.

The headline of that first paper? “Sex orgies of the T&T rich,” an expose by Denyse Renne that had been produced over weeks, resulting in some photographs that we couldn’t publish.

It was all festive, giddy and more than a little bit insane on reflection.

But that lunacy would take a very firm backseat the next morning, as the morning hum of excited conversation and old talk among a group still becoming a working unit stopped when someone noticed the images on the tiny screen that overlooked the newsroom.

I don’t have to tell you what we were looking at. Everyone has seen those images, dozens, even hundreds of times. The planes. The explosions. The flames. The people.

I got urgent permission to contact and source images from Agence France Presse (AFP) and a stream of horrific imagery began to flow into my computer. The photos you know of 9/11 are not the only images that came over the wire services that day.

While there was a general understanding among media houses that the most disturbing images wouldn’t make the paper, the raw feed was unforgettable in its carnage.

“That paper was the best local news presentation of what was a global story from the newest kids on the journalism block in Trinidad and Tobago,” remembers Kevan Gibbs.

“I was told that the paper sold out that morning, and suddenly we were competing with the big boy tabloids like the Newsday and the Express.”

For that week, finding news wasn’t a problem. It was one of those times that the paper practically wrote itself.

Life at The Wire

Photo by Andrea de Silva, October 01, 2002.

That was the beginning of the paper. A troubled, unsettled and globally dramatic first week that played out into three months of almost unceasing turmoil and churn before things settled down and we set about the business of delivering a paper five days a week with a youth-oriented focus.

I’d taken responsibility for at least two pages that appeared each day in the paper, the puzzle page and the comics and horoscope page, asking Dorothy Aché, the grandmother of my good friend Sonya Sanchez and a word puzzle fiend, to go through the dozens of samples of puzzles and word games we’d been sent and she put together a killer selection. Some of those puzzles appear in The Guardian to this day.

I recall at least two conversations with very conservative readers who were upset at having to go through pages of colourful news and youth/event focused coverage to get to the puzzles. I apologised and encouraged them to tear the pages out of the paper after buying it.

As for the rest of it, I reached out to the former Wire journalists I could find for their recollections.

Jhaye-Q Baptiste wrote two columns a week, Bitches Brew and Sex and the Trini.

“Twenty years down the road, with a Covid mask on my face, fans of my Wire columns still see me, and feel moved to let me know they read my work,” Baptiste wrote in an email.

“That is the power of the pen; such is the strength of storytelling. Storytelling is the heart of media.

That is what made the WIRE popular. Readers responded to its approachable, colourful delivery of news, current events, pop culture, et al.

The WIRE was warm. It was friendly. It served the double ‘doables’ of being both engaging and entertaining.”

“A lot of what we learned to practice decades ago, on this little tabloid sister to the Guardian, is the stuff modern social media is made off: shorter, snappier, livelier writing; photos with ‘pop’; dynamism and fun underlined; a more human manner in connecting with readers.

What could the WIRE have become in its bright, albeit brief, existence?”

“Working on it was one of the most satisfying chapters of my Media career. Aside from my columns Bitch’s Brew and Sex and the Trini, I was able to share writing knowledge with amazing fledglings who later established themselves in the field.”

“In fact, there was an overall sense of youthful exuberance— even abandon— in the energy we, the motley staff, manifested in all departments of production. Everyone could see everyone else. Every editor had an open door. Every day was like a little bit of light, even when there were shadows.

Perhaps that’s the glow of nostalgia, but I have a pretty good memory: the Wire was where I was most given room to just work and be happy doing it.”

“Living abroad has made me see Trinidad from other lenses,” said reporter Neidi Lee Sing.

“My time at The Wire helped me to embrace our freedom of the press and uniqueness of Trinidad culture.

It supplemented stories about real life issues which the daily paper couldn’t carry due to time and production limits. The Wire gave me an opportunity to explore my editorial and photography skills, having returned from radio.”

“What I remember most (and most fondly) about The Wire was the challenge and the freedom to experiment with new ideas,” recalls Bonnie Khan who would serve as the paper’s Features Editor and Acting Editor, taking on new challenges as senior staff left the paper.

“It was a step up for me to manage a busy newsroom – not just the pace of work, but finding stories to fill a paper, making tight deadlines and training up new reporters.

I relied heavily on older heads who had more years in the industry than I had on Earth – Irene Medina, Azad Ali, Mark Lyndersay, Andrea De Silva and Cordia Gibbs – the stuff I learned from them serves me well to this day.”

“The highlight and lowlight for me was being part of a team that investigated the plight of street-children in T&T – organising it, bringing it to life on the pages, and chasing the stories.

There was that one instance during the investigation when I had to interview underage prostitutes in Port of Spain with (the late) photographer Andre Alexander, who was all too willing to try to pimp me out!”

“It was a hard-hitting investigative journalism that won The Wire the prize for Excellence in Journalism from PAHO and gave us the credibility we needed at the time.

Young reporters like Denyse Renne certainly proved their skill on it. The Wire was a young, fun and committed newsroom and it really was a great team to have been part of.”

“One of my favourite photos was taken at The Wire,” Keifel Agostini wrote.

Agostini worked at the paper preparing digital images for publication, pulling file photos and scanning material for print.

“It was taken on J’Ouvert morning and features me seated at my desk covered in paint.

I’m not sure what arrangement I’d made to work that day, but I do remember meeting up with the band earlier that morning outside the National Stadium, drinking moderately, then leaving my friends in the band at the top of Park and St. Vincent streets and walking into work.”

“I think I spent the remainder of the morning editing photos for the Carnival section before heading home in the cold harsh light of day to shower and get some sleep and then do it all again the next day.”

“I was a good and safe entry point into the Guardian World as young 25 to 26 year oldie.” said designer Sean Simon who was responsible for the front and back display pages of the paper,

“I felt a bit sheltered working there at The Wire. Maybe it was because we were a professional family. Everyone…seemingly pulling and doing their thing, to get a startup paper running and credible. And at the same time, supportive and ‘celebrative’ of the purpose of why were there.”

“There was a lot of talent involved for sure and the friends made…made for some good memories and at times, life-changing experiences.”

“The Wire was a photographer’s dream,” said Andrea de Silva who I’d hired as senior photographer and in an overdue rush of common sense, made Chief Photographer.

“I remember the anticipation of starting a new publication, it was like the birth of a child that would have to be nurtured and moulded into a well rounded, high functioning and valuable individual.”

“I always believed that if The Wire was given the opportunity, we would have been a force to be reckoned with.

It was photo driven. Every newspaper wants compelling photos on their front page, those that draw the viewer and compel them to get their copy. The Wire used lots of images, and they used them well.”

“I remember on September 11, 2001 while we were contemplating the front page for the following day, 9/11 happened which affected the entire world. We ended up doing wraparounds for days after that devastating event took place.

The Wire shut down in January 2003. I was the Chief Photographer at that time and the staff were merged with the Guardian.”

“Twenty years later, I still believe that given the chance we would have carved out a groundbreaking model in Trinidad and Tobago that would be the gold standard today.”

How did The Wire fail?

The team was strong, the journalism was good, particularly after we began to shed the Daily Mail flavoured tone of the first three months worth of the paper, so what went wrong?

“Circulation revenue covers the cost of newsprint, with advertising paying salaries and profit,” explained Peter Gomez in an email.

“(At The Wire) advertising revenues did not match expectations (so the paper) haemorrhaged money. Newsprint was just about paid for by circulation revenue, but salaries didn’t have the advertising revenue to pay for them.”

This was my one great regret after the collapse of The Wire. Spending most of my time in editorial operations and management and not enough on the larger picture of revenue and spending or, as it turns out, overseeing the production side of things.

According to Gomez, the early press time of The Wire sometimes suffered when it was time for The Guardian to run.

“Unfortunately The Wire started a couple (of) years too early, before the new press was bought,” Gomez said.

“The old press had been refurbished as best it could be, but it was prone to breakdowns. And speeds were not the fastest.”

It was also too early for the Internet, where it would have thrived. My former office at the Guardian had been papered with large printouts of the front pages of international newspapers, but at the time, content management systems were either vertical market and expensive or very much in their infancy.

The Guardian was being coded daily in HTML for publication and our biggest audience would have had no smartphones to view the paper on.

Sample pages from The Wire…

The Guardian was the company’s print revenue mainstream, so any issues with the press were always going to be resolved in favour of its press run. It’s one reason why the working day at The Wire was so hectic.

An early start and fast-paced run to design the paper was driven by a hardline 7pm press time, which meant that the paper had to be done, for the most part, by 6pm.

The other challenge was advertising. Hazel-Ann Nakhid, the robustly capable second-in-command at The Guardian was brought over to start the advertising effort at the new paper, but within a few months had returned to her old job. What followed was a succession of advertising executives who weren’t able to find an advertising niche for the paper.

By the end, I was in a mortal disagreement with the last sitting advertising manager, a problem sorted only on the basis that we would report to Grenfell Kissoon in parallel. Consultation and collaboration had started low and bottomed out to zero.

In the middle of the last week of January, 2003, I got an urgent call to return to the office to meet with Grenfell Kissoon.

I was at my SkyBox service picking up a new laptop, Apple’s Titanium PowerBook and to be honest, that meeting didn’t seem as important as the pending unboxing.

I remember walking into the office with the box, seeing the editorial team seated somberly and then hearing of the decision to shutdown of the paper.

It had been looming for a while.

Norman A Sabga had asked, quite bluntly, at an executive meeting that I attended (a courtesy to my operational role) who would be responsible for recovering the two million dollars the paper had lost.

I remember Peter Gomez shot me a warning look when it looked as if I was going to say something.

The Guardian’s General Manager for Administration, Deryck Omar, was assigned to give more direct management oversight and found myself having to do unpleasant things like go over the call logs of senior reporters Sasha Mohammed and Denyse Renne to discuss the duration of their call times.

I did successfully explain to Omar why signing an attendance book would only insult people who were already clearly putting in more than their required time to make the paper work.

I’d successfully managed to cut down on overtime payments after getting permission to trade time spent on critical after-hours assignments for regular working hours, but the math remained unbalanced.

There were other calculations in play. The Guardian had been redesigning and reconfiguring its approach to relaunch at an even smaller ‘G-Size.’

The need for The Wire was diminished by that strategy and we had a team of people trained in producing a paper that targeted a younger audience and the Guardian needed people.

The Wire may not have attracted advertisers, but I had a folder an inch-and-a-half thick of resumes and applications for employment.

At one point, the paper had so attracted the attention of the staff of the T&T Mirror that I fielded a memorable call from that paper’s head of security who claimed to be willing to bring his whole protective services team over.

Grenfell Kissoon wanted to do a soft closure, shutting down operations over a month. I pointed out that the paper wouldn’t benefit from the extra time.

By the time we convened a meeting that afternoon to discuss the closure with the staff, there was a huddle of reporters from other media houses outside the back gate of The Guardian, The Wire’s front entrance, keen to find out about the closure.

Kissoon was surprised. I wasn’t. Big news doesn’t leak, it surges over any effort to contain it.

The Wire had peaked at around 22,000 copies and levelled out at around 16,000, but it had an outsized impact on both the reading public (survey analysts pointed to high pass-along numbers for the paper) and our peers in the journalism community.

Whether the paper was loved or reviled, it had set about quite determinedly not to be ignored.

Story end.

The final issue of The Wire was published two days after that meeting at Grenfell Kissoon’s office, on January 31, 2003. There had been 366 issues of the paper and one effort at a Weekend Wire.

Media surveys after the closure suggested that the audience of The Wire did not come to The Guardian, they went to The Express, which experienced a surge in readership later that year.

Rounded up, the paper had been published for roughly fourteen months, but it had taken almost two years out of my own life.

I’d taken vows of marriage in May 2000, and the demands of the paper had created some early rough patches but I was fortunate to have a partner capable of riding past them with understandable and quite articulate complaints. But there was still some more work to be done.

Everyone at The Wire was offered employment at The Guardian. Around 30 percent of the staff left for other opportunities immediately.

Today, there are only around three people who worked on the paper still working at Guardian Media Limited. I know of Bernadette Millien, Sean Simon, Nigel Simon and Irving Ward, who began as sports editor and closed the paper as its sitting editor. He now holds a senior editorial role at The Guardian.

My other task was self-assigned. I’d wanted to redesign and bring into one coherent space all the editorial capacity of The Guardian, and I pointed out to Grenfell Kissoon that there was an editorial space empty and available.

It would be a tight fit, but the project became a reality when The Guardian decamped to The Wire space and my design for the new Guardian newsroom, which involved demolishing concrete walls and relocating the IT department was green-lit.

That took another four months and after that, there wasn’t much left for me to do. There wasn’t a role at The Guardian for me that could translate what I’d been doing for the last two years into a position there.

I wrote editorials for the paper for a while, honing a skill that serves me well to this day, but I eventually left at the end of 2003 for a two-year contract in Corporate Communications at Petrotrin.

I would contribute my column and leader writing services to the paper until 2017, when reorganisations at the paper and an unfathomable leadership team (marking my third contretemps with imported UK journalists who raised my hackles) made any further work there untenable.

Where are they now?

It wasn’t possible to contact everyone who worked on the paper and some chose not to contribute, but there are others who aren’t with us anymore.

Journalism lost former Wire freelancers Bert Allette and Rolph Warner. Features editor Sandra Chouthi passed on, as did sports journalist Naz Yacoob and proofreaders Horace Gordon, Michael “Toes” Martin and Lennox Joseph.

- Andy Johnson is a contributor, columnist and editorial writer with the Express, an interviewer and programme host with WESN TV, and a public affairs moderator at large.

- Peter Gomez is Manager, Finance at Electric Sales & Service Co (ESSCO) in Barbados.

- Kevan Gibbs built one of the biggest and longest running events in T&T, Great Fete Weekend, before entering politics in 2010. Today, he co-owns a digital media company in East Trinidad. He has served as Communications Manager to the Prime Minister, Marketing Designer at Digicel, and is currently an Alderman for the Tunapuna Piarco Region.

- Jhaye-Q Baptiste teaches media arts and writes several blogs, which include an archive of recent work as well as early Bitches Brew columns. She makes her photography available at Pexels.

- Bonnie Khan is a Communications Consultant in Italy and The Netherlands.

- Andrea de Silva runs SilvaImage Photography and is a photographer for Reuters.

- Neidi Lee Sing is a supply worker in the Education Sector in the UK.

- Sean Simon is a music composer and Senior Graphic Artist, Guardian Media

- Michael Tikasingh is an IT consultant and computer user coach.

- Keifel Agostini has worked with Apple for the last 16 years and is currently an Apple Watch Software QA Engineer.

Wire staff list as of September 7, 2001

Andrew Johnson, Editor in Chief

Mark Lyndersay, Operations Manager

Hazel-Ann Nakhid, Marketing Manager

Bernadette Millien, Secretary

Charissa Forde, General Assistant

Carol Ou Hing Wan, Receptionist/Cashier

Irene Medina, News Editor

Sandra Chouthi, Reporter

Donna Pierre, Reporter

Bonnie Khan, Reporter

Neidi Lee Sing, Reporter

Sasha Mohammed, Reporter

Michelle Lewis, Reporter

Richard Howard, Reporter

Carla Bridgewater, Reporter

Aneela Maraj, Reporter

Irving Ward, Sports Editor

Nigel Simon, Reporter

Naz Yacoob, Reporter

Brij Parasnath, Reporter

Jaye-Q Baptiste, Reporter

Danielle Ashby, Sub-Editor

Joanne Barsatie, Sub-Editor

Steve Regis, Sub-Editor

Dennis Taye Allen, Freelance Sub-Editor

Horace Gordon, Freelance Sub-Editor

Lennard Joseph, Freelance Copy Editor

Andrea De Silva, Photographer

Curtis Chase, Photographer

Riseé Chaderton, Photographer

Keith Matthews, Photographer

Dean Payne, Photographer

Trevor Burnett, Freelance Photojournalist

Sean Simon, Artist

Kevan Gibbs, Graphic Designer

Masood Ali, Imaging Technician

Germaine Coggins, Sales

Brian Saunders, Sales

Sean Heywood, Graphic Artist

Denise Boatswain, Advertising

Julie Andrews, Classifieds

Keisha Forbes, Sales