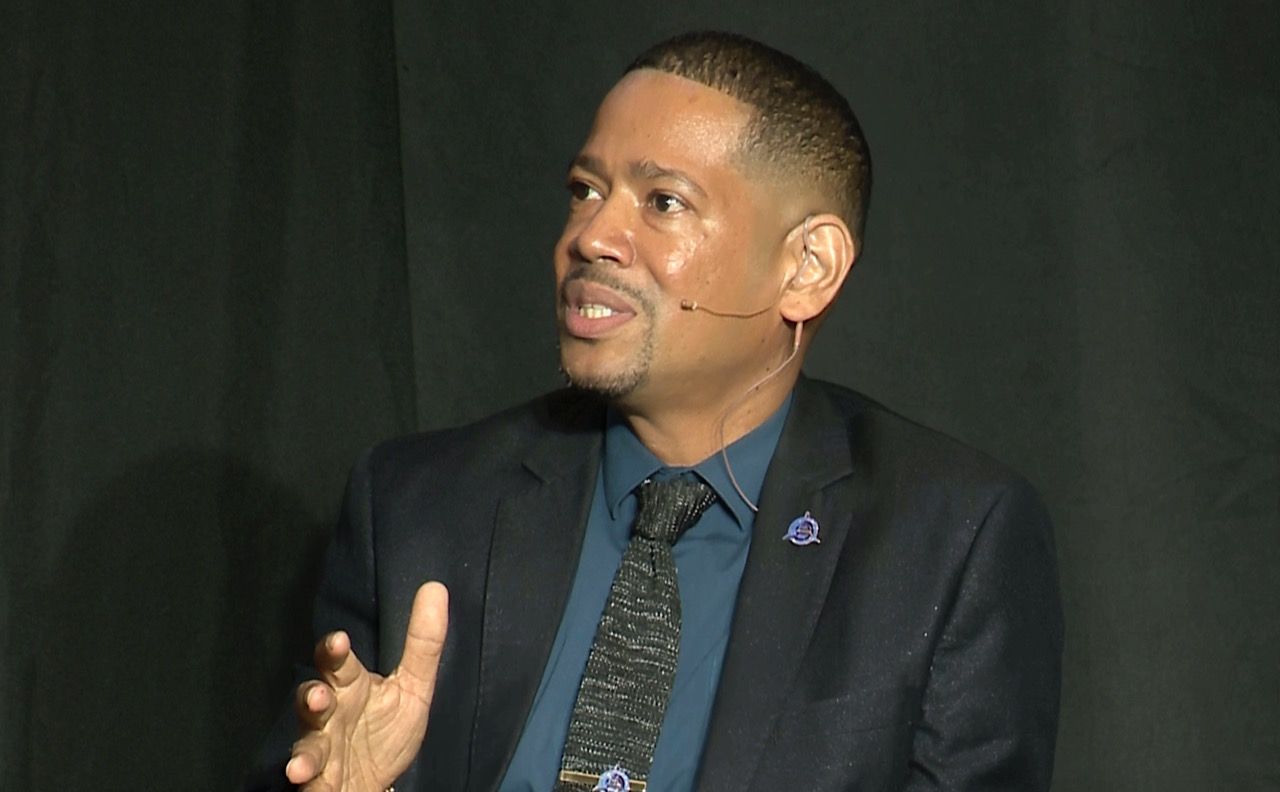

Above: Matt Mullenweg. Photo by Christopher Michel/Creative Commons licensing

BitDepth#1481 for October 21, 2024

In September, Matt Mullenweg, co-founder of the successful WordPress software ecosystem threw down the gauntlet in a startling battle with WPEngine, a company that uses WordPress as the basis of a managed hosting business that targets customers who want a turnkey experience with significant support.

WPEngine’s business is estimated at US$400 million annually.

Mullenweg did not mince words in a post on September 21, taking issue with WPEngine’s disabling of a core WordPress feature.

“They disable revisions because it costs them more money to store the history of the changes in the database, and they don’t want to spend that to protect your content.”

“They are strip-mining the WordPress ecosystem, giving our users a crappier experience so they can make more money.”

This is hardly the only issue that Mullenweg, the CEO of Auttomatic, the commercial arm of WordPress, has raised with WPEngine and it shouldn’t come as any surprise that it’s all about money.

It also shouldn’t surprise you that he also has a connection to Trinidad, since his personal blog, ma.tt, runs on our domain. He wrote about that in 2008 (ma.tt/tag/trinidad/).

Things took a darker turn in the dispute with WPEngine and its majority investor, Silver Lake, after Mullenweg instituted an unprecedented ban, denying WPEngine access to critical WordPress resources since September 25.

WPEngine and the websites of its customers were blocked from the WordPress log-in system, theme and plug-in updates and other background processes that enable a WordPress website.

“Pending their legal claims and litigation against WordPress.org, WPEngine no longer has free access to WordPress.org’s resources,” Mullenweg wrote on Auttomatic’s blog.

Mullenweg has since acknowledged that some WordPress staff disagreed with this slash and burn tactic and had taken buyouts.

Understanding what’s happening here requires at least a nodding understanding of the open source software ecosystem.

Under open source licensing, a product can be both free and commercial, but regardless of the distribution approach, using open source software requires programmers to return time and programming capacity to the core ecosystem.

At the heart of managing this potential free-for-all is the General Public License (GPL), which governs how contributors work with the primary code base.

The WordPress brouhaha is hardly the first challenge that the open source model has been managing.

Linux is a popular UNIX based operating system that is distributed in multiple variants (including Android), which all make use of the core Linux kernel pioneered by Linus Torvalds.

In 2023, the most successful commercial implementation of Linux, Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), owned by IBM, created a stir by changing the terms of use for its free version, CentOS.

Programmers doh stick, so new variants or forks of the code immediately appeared, prompting push-back from RHEL.

While lawyers may be called on to adjudicate these conflicts, their presence ultimately isn’t as important as the talented members of the developer community and their willingness to align their interests and support with a project.

Linux and WordPress share a core principle. They are both communities first and businesses second. The businesses benefit from the work that individual developer contributors bring to the core code.

RHEL targets the specific needs of enterprise customers, while Canonical maintains a widely forked and popular version of Linux, Ubuntu, the user-friendly face of the UNIX operating system.

But there are uncounted numbers of Linux distributions, also known as distros, because anyone can download a package, make changes and upload it as a new distro.

Mullenweg has been particularly vociferous about the token contributions by WPEngine to the WordPress project, noting that Auttomatic contributes 3,915 hours each week to WordPress compared to WPEngine’s 40.

If this was a business matter that would be a non-issue, but open source lives or dies by the vigour of its contributors.

Here’s a lived example of how open source helps the wider public. Over the past four years, I’ve been helping a friend keep an old PowerMac G5 usable.

The last G5 was manufactured in 2006 and over the years, web browsers stopped supporting the obsolete version of the MacOS it runs.

The solution was found in forked versions of the code for Firefox and Chrome that were being updated and maintained by independent programmers, free of charge, for an almost nonexistent audience.

That’s not something a business, even one run as a nonprofit would have considered, but programmers are wired to solve even fringe use problems, and we are all the richer for it.

There is no forked version of Safari, Apple’s own web browser, because it isn’t open source, though its rendering engine, WebKit, is.

Three weeks after launching his initial broadsides against WPEngine, Mullenweg forcibly forked Advanced Custom Fields, a critical page building plug-in by WPEngine, replacing it on the WordPress repository with Secure Custom Fields, essentially the same plug-in but managed by Auttomatic.

It was a heavy-handed move, particularly in a situation that began with a trademark violation accusation and has now led to Auttomatic withdrawing the means of production for a running business.

Mullenweg argues that he has been in discussions with WPEngine for more than a year, but it’s almost impossible to pursue any kind of sensible negotiation while Auttomatic continues to attack its perceived rival on an almost daily basis.

WPEngine has a dubious reputation in the community at large, but its turnkey solutions have won clients like Stanford University, Petco, Thomson-Reuters, Warby-Parker and Tiffany.

It’s hard to see how breaking such high-profile, well-trafficked websites represents a win for the platform that runs 40 per cent of all websites globally.

There have been calls for Mullenweg to resign, but it’s clear that he needs to start by quitting his current approach, which will only enrich lawyers and damage the WordPress community the longer it continues.

Like any dad, Mullenweg must decide whether he loves his child, WordPress, more than he hates its money-hungry boyfriend.

[…] Caribbean – In September, Matt Mullenweg, co-founder of the successful WordPress software ecosystem threw down the gauntlet in a startling battle with WPEngine, a company that uses WordPress as the basis of a managed hosting business that targets customers who want a turnkey experience with significant support… more […]