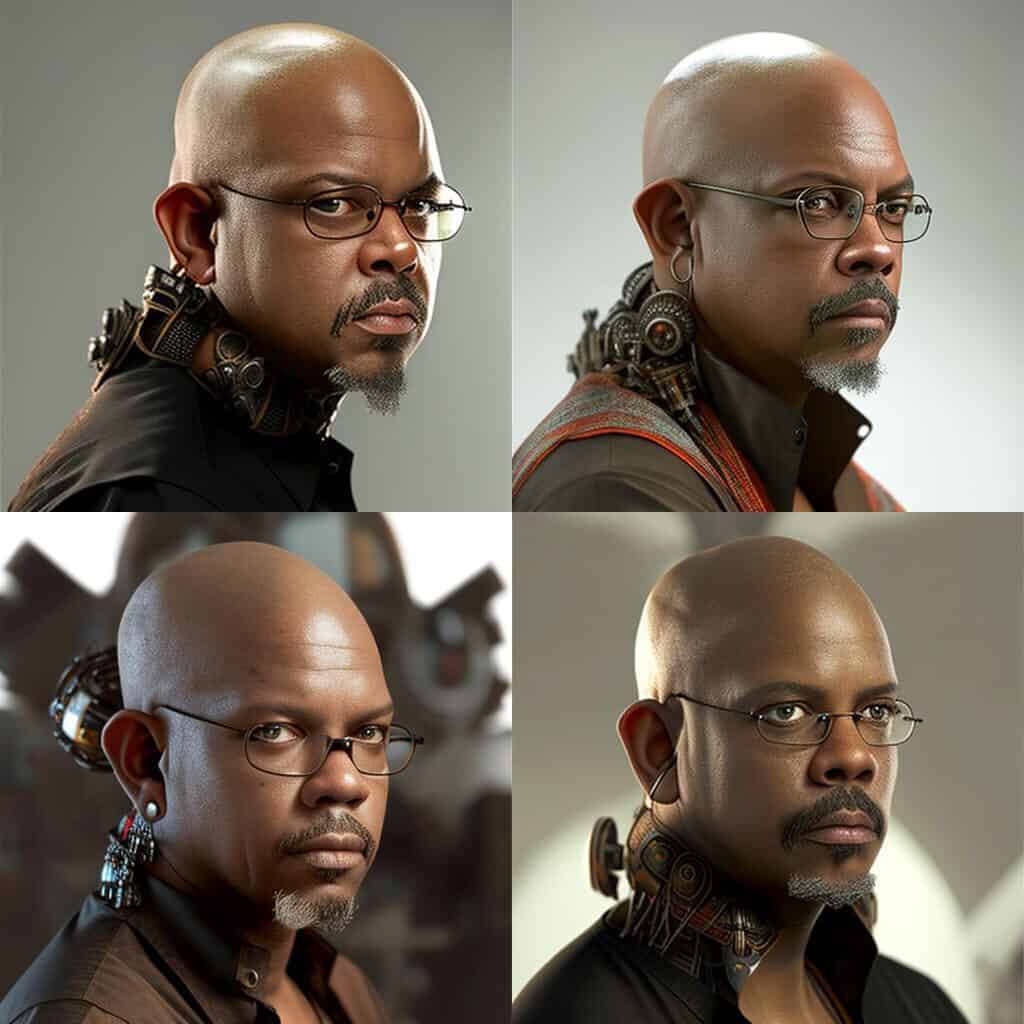

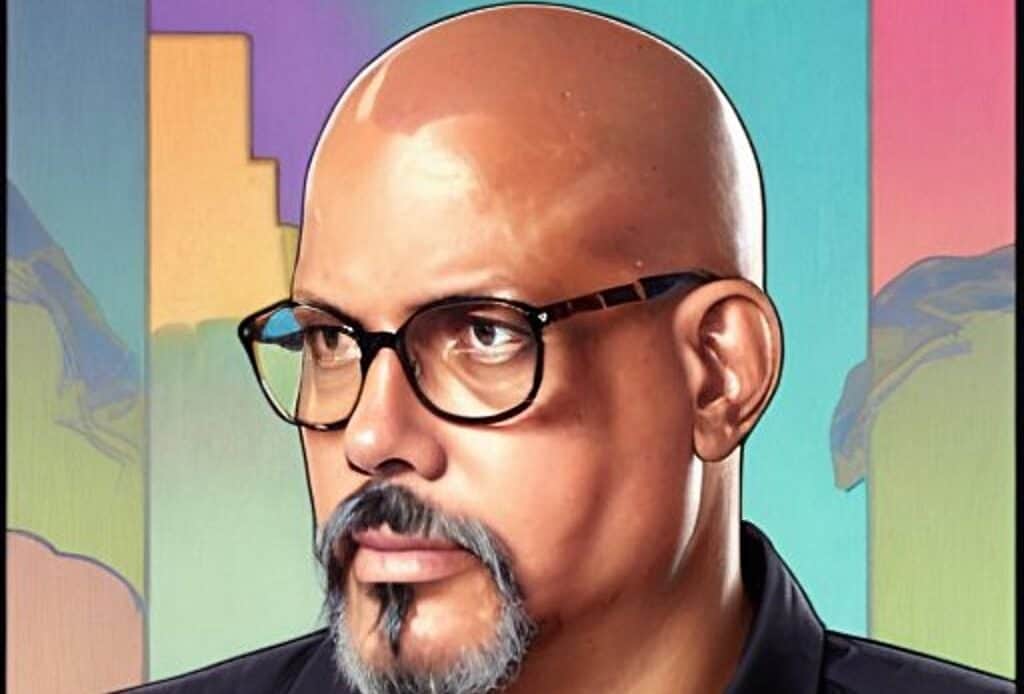

Above: Lensa interpretation of a self-portrait.

BitDepth#1387 for January 02, 2023

In the last six months, the art world and photographers, have been tossed into the spin wash of artificial intelligence (AI) technology with the emergence of multiple computing clusters that turn text and image input into output that looks very much like art.

The technologies in play here emerged from the reversal of research into image recognition technology.

Scientists, having considered deeply what might make images recognisable to computers, flipped the script and began to consider what might emerge from computers when they are asked to create art.

There are two main ways this is being done across a growing number of image generation portals.

In some, you enter a text prompt, a description, collated keyword style, of what the image should contain or be influenced by.

That might include locations, art styles, popular people and other descriptions that collectively influence what these computers synthesise.

In others, you upload an image and the software goes freestyle on it.

I opened a half-dozen of these tools, many of which demand payment up-front and ended up trying the popular MidJourney portal and Lensa app.

Lensa, from the company that created a briefly popular prism art filter app a couple of years ago, is a general purpose, AI powered image enhancement tool.

For a fee, it will also upload a batch of your selfies to an AI server to create fanciful avatars.

Three hundred photos and US$7 later, my collection is an agonising gallery of all the ways that AI can get human features and limbs wrong.

For some reason, Lensa feels rather overwhelmingly that I should also wear open-collar suits and a variety of hats, from baseball caps to smart looking fedoras.

Lensa’s output seemed almost entirely appalling to me, but I’m a fussy photographer.

MidJourney is accessible through bots running on a Discord channel. When you sign up, you get 25 free chances to create something digitally amazing.

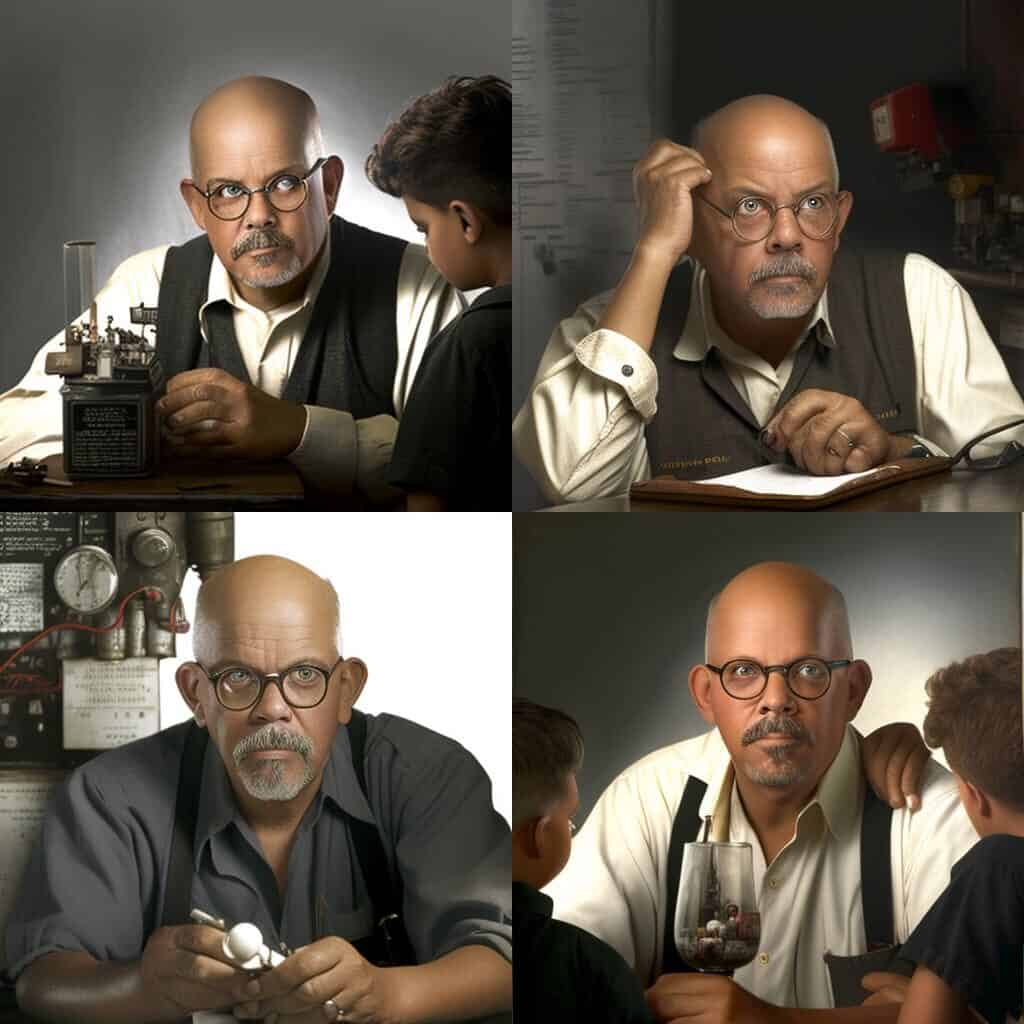

As with Lensa, I tossed various photos of myself at the software with a range of prompts and the results were equally unusable, but more interestingly so.

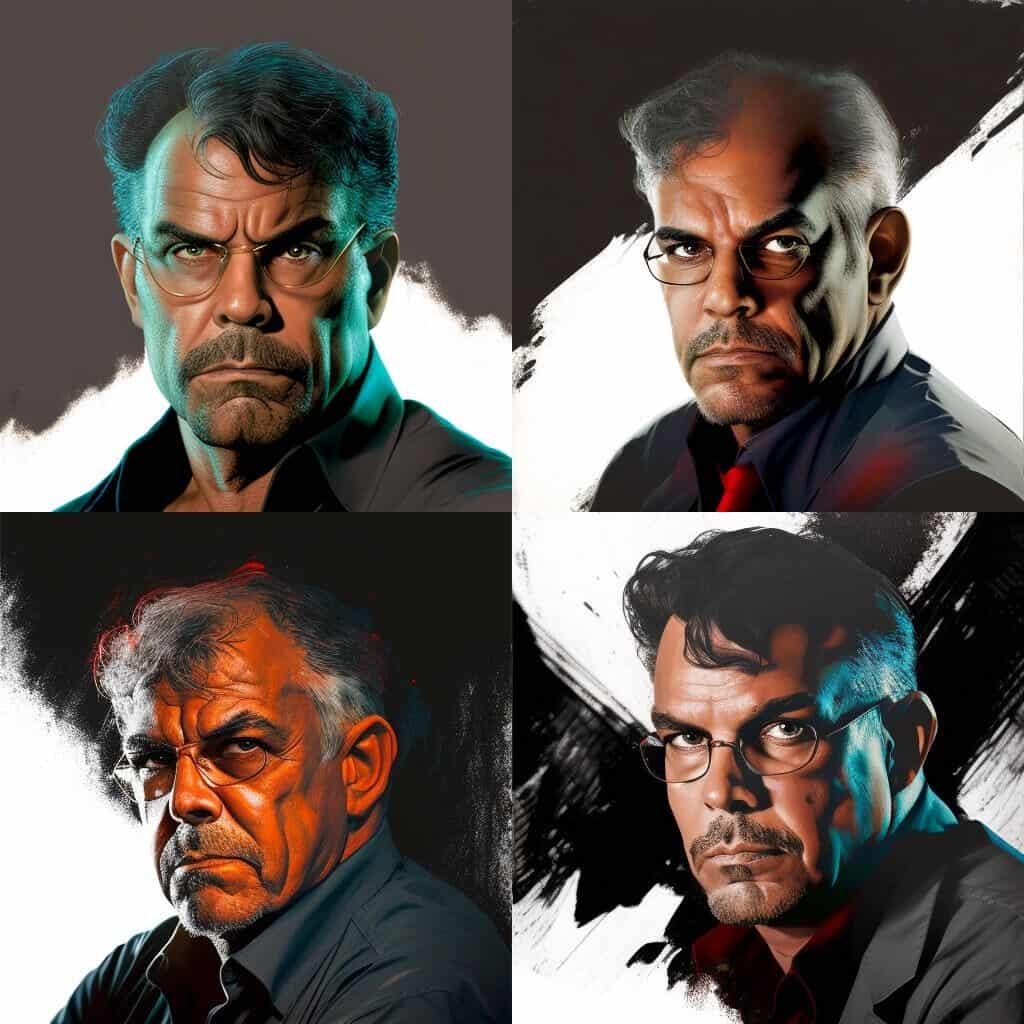

MidJourney seemed to have no analogue for my caramel skintone and frequently jumped to Caucasian renditions. When I added prompts like “African” it immediately jumped to a kind of generic chocolate tone.

Every other rendition of my submitted portrait added hair and when I added the prompt “bald” it immediately switched from either ageing me or adding hair to delivering an unrecognisably youthful and cherubic version of my image.

These MidJourney generations were done from self-portrait headshots I have on file. The results are heavily dependent on the prompts that are used.

MidJourney works on the submitted image using the text and from my results, there is no question that understanding prompt text is crucial to AI art.

I asked two local designers and artists about work they have produced using AI. Ian Reid, art director of Reid Designs is refining his prompting.

“You will no longer need to pay a mas designer to render costume ideas,” Reid explained. “I will do that for you by being the prompt engineer. Right now I am learning everything there is to know about prompting so I can get what is requested.”

“I am interested in rendering images that clients request that we can’t find in [stock image agency] Shutterstock. ‘Young Indian woman from Trinidad using a phone,’ for example. My goal is to see if I can slot into a niche where I can provide a service to clients who can’t find a solution anywhere else.”

But where do these new images come from? Image AI computing clusters are trained by analysing a selection of images submitted to it.

The most powerful AI tools have been trained by scraping publicly available images across the Internet, assimilating them by the billions.

It’s here that the mystery of image generating AI becomes even more complex.

This massive database of images gets sorted and analysed using deep learning, which processes information using algorithms inspired by brain function. It’s the most sophisticated form of AI, but things get even more confusing from there.

All that information is then categorised in what mathematicians call the latent space, which organises and references the processed data in dimensions that far exceed the three that humans use.

It is here, when urged by prompts, that these AI engines create their output.

That computing latent space is either an approximation or an extension of the free associations that the creative mind makes based on sensory input, but it proceeds unhindered by human limitations or experience.

That’s why thumbs inexplicably appear in heads among other Dali-esque incongruities. Salvador Dali himself might have been the best person to interpret latent space for us.

It’s clearly early days yet for the technology and all these users are continuously training these clusters through acceptance and rejection.

They will only become more accurate in their synthesis of art styles, image components and merging of elements.

“For my personal art, I will never use it,” said creative director Anthony Burnley (Reid and Burnley’s full interviews are here).

“Because it’s not my art [but] for my commercial profession, by all means. I see it as a form of clip art on steroids. Or stock art, or stock photography, they all come from a similar place and seek to solve similar problems. The challenge is in who will use it the best.”