Above: Photo by Wavebreak Media/Depositphotos

BitDepth#1362 for July 11, 2022

Cookies are tiny text files that a website downloads to a browser that retains information about the session visit.

Cookies can retain any or all of the following information about a web user.

• The name of the website that you clicked on

• How often you accessed information on a website, and the time you spent there

• Your account credentials, location, IP address, address and phone number (if entered)

• Items you put in a shopping cart.

When the internet was a simpler place, this was a convenience.

It was nice to revisit a website and not have to log in. We smiled when an ad for an item we browsed recently showed up on another website entirely.

Then the internet got more dangerous, and cookies got pincered between increased attention to the privacy of internet users and the decision by Apple and the Mozilla foundation to limit their reach.

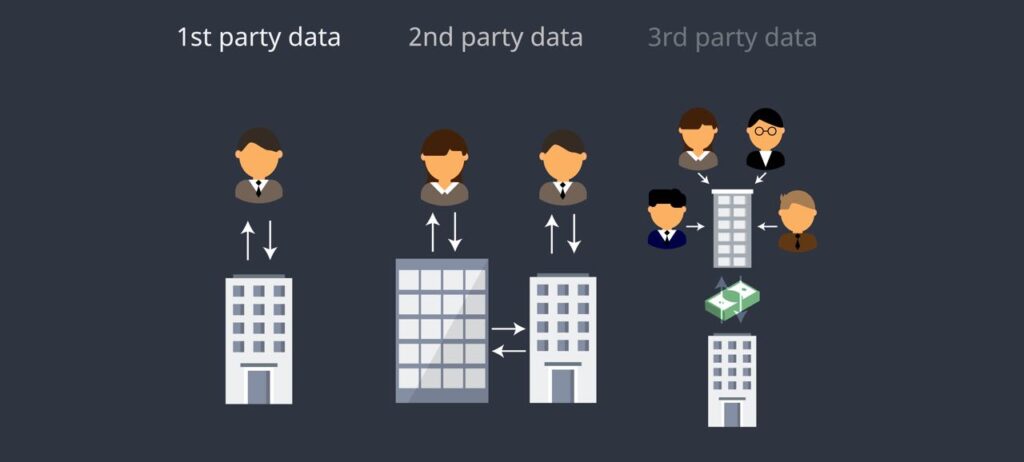

There are three kinds of data that can be collected for business use.

First party data is information that a company collects through its interactions with its customers or audience.

Second party data is information that is gathered by a trusted partner. This information is normally not for sale and is usually shared for the mutual benefit of those involved.

Third party data is information gathered from someone you don’t know using methods of which you may be unaware. It is normally sold or licensed for advertising and marketing.

Since 2012, the EU has required websites to have user consent before saving cookies.

In 2017, Safari introduced its first version of an option to block cross-site tracking. In 2019, Firefox began blocking third-party cookies by default, followed by Safari in 2020.

Curious to find out your tracker profile? Use this tracker report from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Block trackers with disconnect.me.

Feeling the pressure of increased demand for user privacy, Google announced that it would begin blocking third-party cookies in Chrome in 2020, but in the face of outcry from marketers and vendors, postponed termination to the end of 2023.

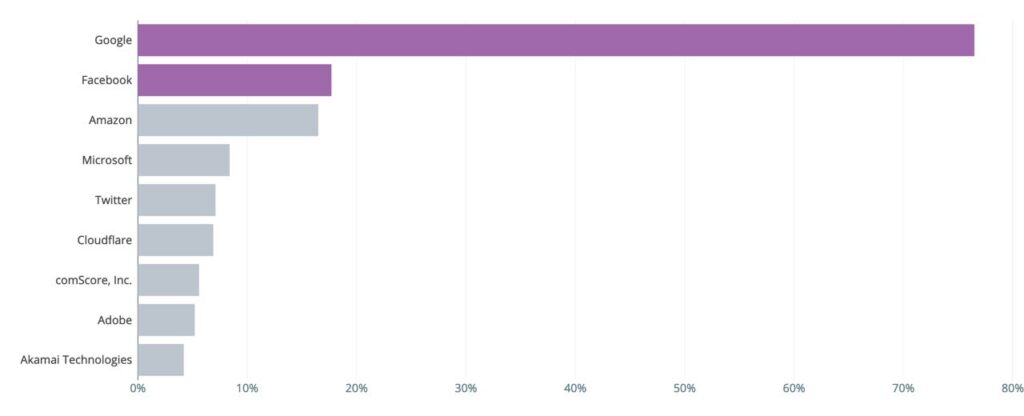

Chrome currently has 63 per cent of the browser market, so when it begins blocking the collection of third party data, it will effectively end that method of information gathering.

But that won’t end tracking. Google currently has trackers running on 76 per cent of all web traffic. There is an invisible Facebook tracking pixel on 18 per cent of websites.

As the dangers of cross-site tracking and insecure transmission of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) became more apparent, legitimate worry arose about the vast pools of PII data that companies were gathering and selling to marketers.

Third party data gathering is a mass harvesting and aggregation process and in gathering this information, careless coding can create security problems.

First party data is roughly equivalent to the contact information you have gathered in your personal address book.

Second party data is information you got from your good-good pardner’s address book.

Third party data is information you got from a fella who know a fella.

First party is difficult to acquire, but immensely valuable. Second party is good, particularly if it is trustworthy. Third party is cheap and widely available, gathered using techniques that began to raise eyebrows and led to the great cookie crush.

Google has been working on replacements, started with the Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC), which sought to aggregate anonymised customers by interests.

The company has now moved on to Topics, a new effort to gather more carefully limited information about customers based on their browsing patterns.

There is also experimentation with data clean rooms, which are supposed to create scrubbed data sets that will guide marketing efforts. There are concerns about how thoroughly data can be scrubbed before it becomes useless for marketing.

How well media houses know and understand their customers will become critical with the end of third-party cookies. McKinsey estimated in 2021 that the industry could lose as much as US$10 billion in advertising revenue and that’s a hit that it can’t take.

Facebook, Google and Amazon successfully created models in which users cheerfully gave up deep data about themselves which fuelled massively successful advertising businesses.

Amazon in particular uses its deep understanding of its customers to sell like no salesman ever had before.

Globally, major media houses have started creating their own first party data capture regimes, if they didn’t have one in place before.

It isn’t so much a problem as it is a tremendous opportunity.

Media houses that develop systems that deepen their understanding of their audiences, can more effectively build engagement and become more responsive, but they must also plan to offer value in exchange for coveted audience profiles.

First party data can move the trade in advertising inventory from blind auction to direct negotiation, while improving the relationship between journalist and audience.

But TT media houses are notably data shy.

That’s partly because of the history of the business, when news was largely tossed blindly out of a van or into the aether, but even an annual independent survey of media penetration died because some companies funding the analysis didn’t like the results.

Vagueness is not expected in digital publishing, and it demands a fundamental rethinking of the role of the audience in shaping successful news uptake.

Without a plan, without profiles of their audience, digital media houses will face real challenges in attracting effective advertising.