Above: Apple’s Mac Studio is dwarfed by the display real estate it is capable of driving. Photos courtesy Apple.

BitDepth 1345 for March 14, 2022

On Tuesday, Apple announced its new desktop computer, a machined aluminium box it calls the Mac Studio.

Old school Mac users might blink and squint at the Power Mac G4 Cube of 2000 reincarnated as an art piece.

The Cube was beautiful, with a machined metal casing sheathed in a polished acrylic case but the device was hamstrung by middling power and severely limited expandability.

The Cube looked great on a work desk, but it found few buyers, and the product failed spectacularly; ending its manufacturing run just over a year after it was revealed.

What replaced it four years later was the Mac Mini, a more focused effort at creating a compact desktop computer that someone would actually want to buy.

Leveraging improved motherboards for computers, the Mac Mini was roughly the size of the top quarter of the Mac Cube, a flat cuboid that looked like a metal single-serving pizza box.

Starting with the PowerPC G4 chip, it would continue to become the introductory developer’s device for the new Apple Silicon chips, heralding the new generation of in-house processors from the company.

The new Mac Studio looms over the Mac Mini, but it’s no tower. It has the same depth and width as the Mini at 7.7 inches square, but stands taller at 3.7 inches to the Mini’s 1.4 inches.

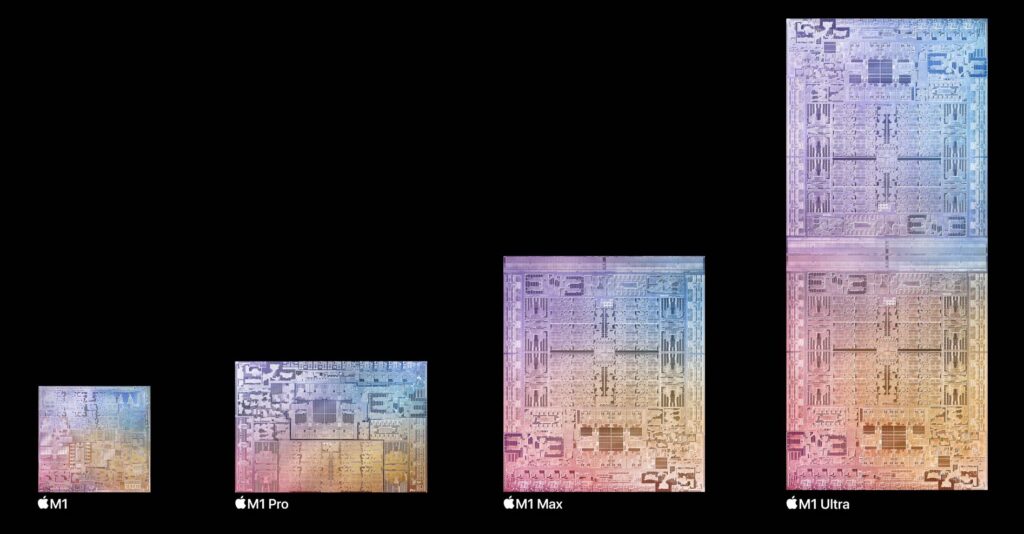

The Mac Studio also taps the power of the M1 chip, introducing a new variant, the M1 Ultra which fuses two M1 Max processors to double existing processing power to 20 processor cores and the GPU core count to 48.

Apple brags that with that graphics horsepower, the Mac Studio can drive four of its costly XDR monitors at 6K and a 4K display.

Configuring a Mac Studio really calls for a big up-front investment, because Apple’s current logic board designs don’t support after-purchase upgrades.

If you use apps that make use of multiple CPU cores, then going to the top-end Mac Studio makes sense, but expect to pay around US$3,999 for an upper-midrange configuration with 64GB of RAM and a one terabyte SSD.

By comparison, the top-shelf current model Mac Pro starts at an eye-watering US$5999 which you can configure to cost more than US$20,000 without choosing all the upgrade options available.

Given those price ranges, investing in a Mac Studio or Mini seems cheap even when compared to buying one of Apple’s eye-wateringly expensive monitors which range in price from the new 27-inch monitor at US$1,599 to the 32-inch Pro XDR display at US$4,999.

But, the real question is how well does the new Mac Studio stack up against its real competition, the tower systems that Apple sold between 2006 and 2012?

Those were not casual machines, and I say so because there’s a 2009 model on my desk in front of me. People who own these systems do not plan to give them up. Ever.

They are the conceptual opposite of the Mac Studio and not just because they are heavy, huge metal boxes that you must bend at the knee to lift.

In those old “cheese grater” Mac Pros, you can upgrade everything, so they have kept pace with newer models well past their planned life.

You can stuff six modern hard drives or SSDs into them and with some industry, as many as seven.

A legacy Mac Pro user will only be tempted by the Mac Studio if they run software that can actually use a 10 or 20 core CPU.

Processor intensive software is coded to spawn multiple task threads that make use of all available cores and the people who use those apps know exactly what they need.

Microsoft Word and Firefox won’t work any faster on ten cores than they will on four, and most users wont see any difference at all.

For the average user the difference in day to day experience between a Mac Studio and an 8-core Mac Mini with 16GB of RAM costing around US$1299 is bragging rights.

The Mac Studio has its audience, but it isn’t going to woo anyone with a 11-year old Mac Pro any more than 2013’s cylinder-shaped Mac Pro revision did.