Facebook’s Menlo Park Campus. Photos courtesy Meta.

BitDepth#1327 for November 08, 2021.

Facebook’s renaming of its holding company to Meta is cynical, almost childish and most appallingly, quite likely to work.

As a strategy, it’s meant to change the conversation from an evaluation of the social media giant as a brutally disinterested purveyor of hate speech, vitriol and conflict to deliberations on a goofy logo.

The strategy has largely worked though, and has been further fortified by news that Facebook is now (kind of) shutting down its facial recognition software.

The bad news about the company’s operations has been pushed off the first two pages of search engines for the term Facebook, essentially burying the bad news.

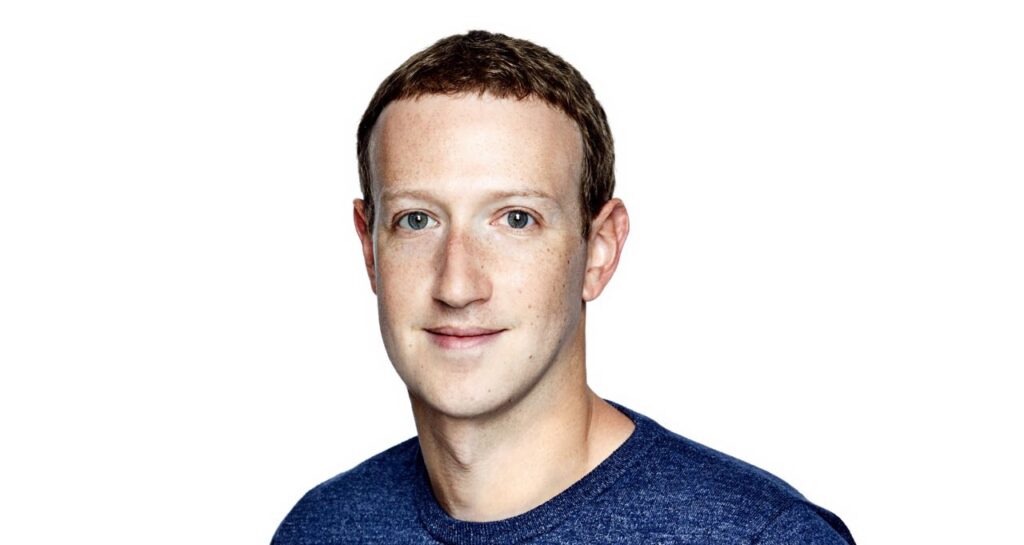

Facebook’s CEO and majority shareholder Mark Zuckerberg wants us to now begin thinking about his company – which started as a ranking of Harvard student hotness in 2004 – as the next major virtual landowner in entirely digital realms, from Oculus-powered bitscapes to dubious efforts at cryptocurrency.

That’s where we will collectively become avatar sharecroppers to further gild the company’s fortunes.

In a press release, the new Meta announced that: “The metaverse will feel like a hybrid of today’s online social experiences, sometimes expanded into three dimensions or projected into the physical world.”

“It will let you share immersive experiences with other people even when you can’t be together— and do things together you couldn’t do in the physical world.”

The company will kickstart this project with a $50 million investment over two years and report its finances in two business sectors, Reality Labs and Family of Apps, including Facebook, Messenger and its acquired apps, including WhatsApp and Instagram.

Zuckerberg has already made it clear that he doesn’t want to talk about things like the incidents of assault and abuse enabled by his platform, proven manipulation of voter opinions or even the quiet enabling of channels of hatred and prejudice that are almost unprecedented in modern communications history.

It’s a remarkable, if upsetting achievement, that Facebook managed to evolve from a crass and misogynistic website into a crass and often vulgar collection of mankind’s basest failings without ever offering evidence of a point of view or a smidgen of creative style.

The platform’s success is seductive in its industrious facelessness, offering up birthday wishes alongside gaslighting and racism in one endless stream of almost uniformly useless and ill-informed factoids accented by the company’s calm blue signature colour.

While doing so, the social media giant vacuumed up a staggering share of online advertising while reconnecting old friends across decades of lost contact.

So many recent revelations about Facebook’s approach to business align with the clear signals it sends to its users.

There’s an old saying about web services; if you aren’t paying for access, you are the product, and Facebook’s application of addictive technology to social behaviour on its platform is a particularly stark example of the model.

The first thing the company did in developing its platform was to trivialise the term ‘friend,’ translating it from a social convention that required time, patience and attention into a couple of clicks, initiating a digital call and response that required nothing more than casual, disengaged interest that’s echoed, though never deepened, across more than a decade.

By gamifying likes and making friends numbers a tally to be pursued, Facebook successfully transformed social interaction into a twitch e-sport, sending millions chasing tallies of thumbs-aup icons while compiling lists of strangers that have no link to real world relationships.

Is it any surprise that after turning billions of human interactions into blips on a screen, Facebook’s next goal would be the virtualisation of human society?

Rest assured that if there is profit to be had in the metaverse, it will be found by Facebook, but it probably won’t be any good for mankind.

In a notable example of how Facebook giveth and manifestly taketh away, the company pledged US$100 million to help journalism in 2020, while simultaneously sucking billions in online advertising from publishers and continuing to bury primary news sources on its platform.

The company’s hopes for creating an equally commanding presence in its singular metaverse also quietly ignores the fact that there are already multiple digital metaverses in operation.

They have been around ever since the first massive multiplayer games crawled sluggishly across the dial-up connections of the early internet.

While the lessons about human nature we’ve learned in those gaming interactions haven’t been as depressing as Facebook’s naked manipulation of emotional response, they suggest that in practice, a metaverse tends to be a lot like the meatverse.

I’ve witnessed a tween near tears after being told to make their avatar skin match their own skintone as a condition of playing Roblox.

Several of her “friends” on that platform simply walked away from her avatar, cooly dismissing her in their chatboxes, “Oh, you’re an ni**er.”

Abuse and digitally enabled danger are not unique to Facebook, but the company’s carelessness about the real and potential dangers on its platform continues to be deftly evaded or ignored.

There’s nothing meta about that.