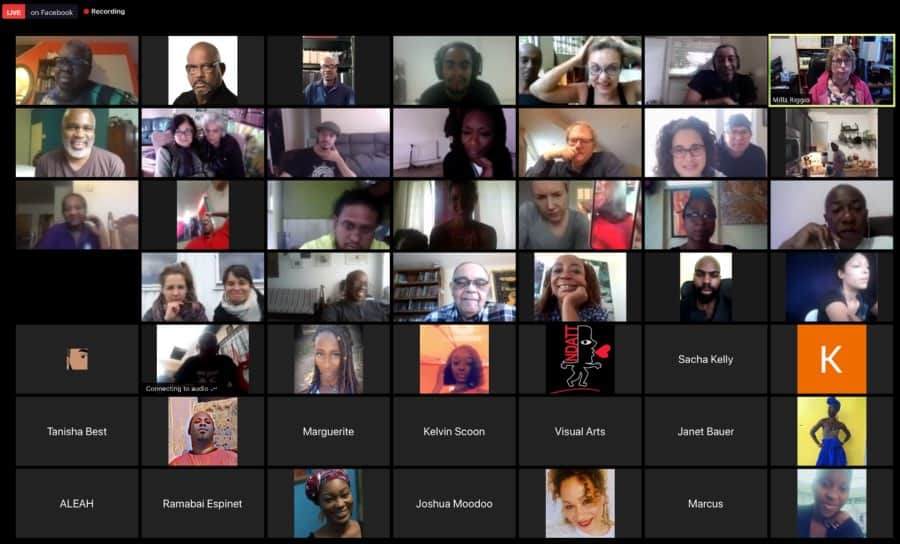

Above: At its busiest moment, more than fifty people, from as far as Norway, gathered on Zoom to remember the late Tony Hall.

BitDepth#1248 for May 07, 2020

I arose before dawn last week and attended a wake, or more properly, a remembrance of Tony Hall.

The Facebook Live event convened at 5:45am in honour of Hall’s love of the dawn, particularly as expressed in Carnival’s J’Ouvert, which he codified as a theatrical approach dubbed the Jouvay process.

A quote attributed to Hall on the Facebook memorial described the process this way…

listen to silence.

jouvay is an availability where every restriction or obstacle is an opening or portal or new dawn revealing silence.

Hall wasn’t a friend. A friend would know your wife’s name, how many children you had, your address.

Yet he had touched me deeply enough that I would set an alarm for him, the memories clear and true.

I knew him since I began my career, an enthusiastic teenager trying to find my way in the more limited creative landscape of Trinidad of the late 1970’s.

I met him for the first time on my way out of Banyan in the late 70’s, when I’d worked with the group on its last year of grappling with the diffidence of TTT in producing a show for the only television channel.

After working as a cameraman on a pilot for the FPA funded series Who the CAP fits, I realised that the deeply collaborative nature of early video production did not suit me.

After the group won the contract, I sat in meetings to discuss the story, hopelessly out of my depth, and it was there that I encountered Hall’s style of creative development, a gently combative nudging of story development away from stereotype and expected tropes into a quirky, very local realm of performance that blurred formal staging and the engaging comedy of roadside picong.

In so many of his photos, Hall is pictured as serious, intent, sober, but his reality was so very different, his charm and wit rippling through every casual conversation.

He was encouraging when I appeared on the first few episodes of Gayelle The Series, a weekly television production (presenting theatre reviews), but I soon dropped out again after I became uncomfortable with being recognised widely, a by-product of appearing on “the people TV.”

Hall, who was a careful and calculating performer as well as a skilled and deft offstage creative, could balance both with a remarkable cool and assurance. I admired it, but couldn’t emulate it.

Milla Riggio recalled Pundit Ravi-Ji saying that “Tony was both visible and invisible.”

It was a feat he’d pull off repeatedly, even as he navigated the unforgiving space of local cultural invention to create plays, musicals, video productions while enabling fresh thinking in a new generation of creative performers.

We’d meet for the last time when he reluctantly helmed a transitional phase of Trinity in Trinidad – a collaboration between the Hartford, Connecticut school and UWI – on my proposed coaching of a new student.

“Well,” I remember him saying, “you’ve done this before, so you know what to do.”

And I did. And he knew it. So I proceeded, certain he was there if I needed help, but buoyed by his quiet confidence.

The screen LEDs cast a unifying glow on gathered faces from all around the world, a conversation crackling through a Zoom-enabled hearth.

So much of that effort to understand his massive legacy was the source of emotional grappling on Friday morning last week as theatre practitioners gathered, first on a Facebook Live broadcast hosted by Penelope Spencer and Michael Cherrie and produced by OMGTT’s Stephen Doobal for NDATT and then on a lively Zoom chat.

If the Facebook live event was a tidy memorial, the Zoom conference was undeniably a wake. The group assembled to talk for almost two hours were searching for a digital replacement for the quiet conversations outside a church or at the graveside, the confessionals and storytelling shared in private remembrance.

The screen LEDs cast a unifying glow on gathered faces from all around the world, a conversation crackling through a Zoom-enabled hearth.

But the correlation is imprecise. Both events happened before Hall was laid to rest, and represented an effort to fill a gap in collective grief that couldn’t be easily filled with bits.

Digital presence is a quite different experience from the smell of crisply ironed clothes at a funeral, hearing the patter of dirt on coffin wood, tasting the sting of straight booze at a wake pushing down sorrow and liberating sweeter memories.

Across almost four hours of memorial and remembrance, the breadth of Hall’s presence in theatre, television and teaching flared to life, a lifetime of quiet, almost unheralded work celebrated with love and enthusiasm.

“If daddy could see this,” Mauri Hall said of his father, “he would be blown away, he would say, ‘but this is amazing’.”

In a time of Covid-19, with grief sharply separated from physical presence, the appreciation of Tony Hall’s quiet theatrical revolution would be neither televised nor broadcast, it would be streamed.