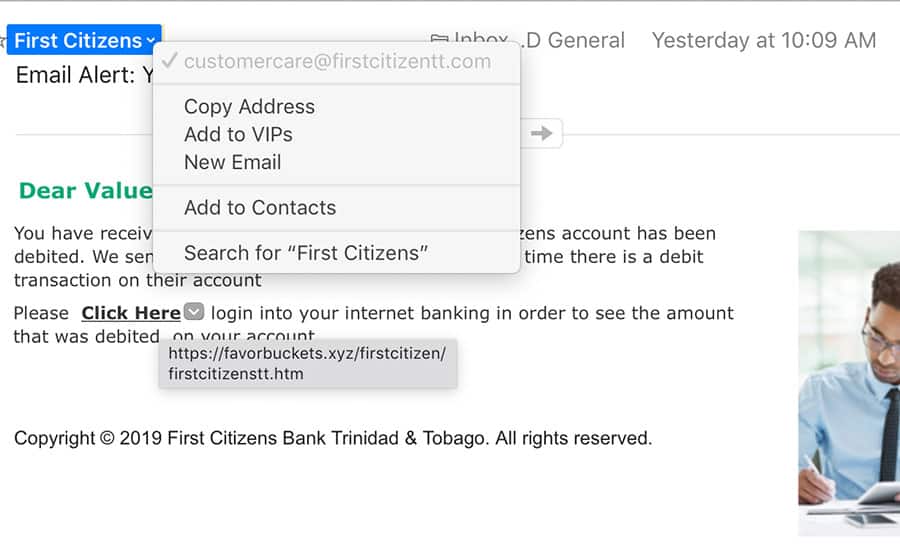

Above: A screenshot of the phishing email. The faked sender email is an actual First Citizens Bank customer care email, but the link to check the debit leads to a phishing website. Hovering your cursor over a link will reveal the underlying email address in most email clients.

BitDepth#1215 for September 19, 2019

Rod and reel fishermen pride themselves on how attractive they can make the bait they cast, spinning it stylishly into the water at the end of an almost invisible line.

Online scam artists rarely take that kind of time with their efforts to encourage people on the web to do something careless with their personal information.

Most efforts at what’s called phishing, a contraction of phoney and fishing, are sloppy, relying on the statistical advantage of reaching a vast number of people via spam emails and depending on inattentiveness in their reading.

It’s surprising how obviously fake the efforts are, and that’s probably because so much is sloppy and careless on the Internet these days.

Some of that is the mad rush for “authenticity” which holds that scrappy is synonymous with realistic, so many efforts at duping people into doing something quite stupid fit right into that ethos.

A year ago I did a post about a scam that was making the rounds that’s since become my most read post.

That lure leveraged the possibility that the recipient might have been doing something very inadvisable in front of a camera-enabled computer while visiting an Internet pornography website.

To add a garnish of authenticity to the email, it included a password that had been gathered from an old privacy breach as proof that the nonexistent video the emailer had surreptitiously made of the inadvisable activity was real. Payment in Bitcoin was then demanded

That put three axes of potential success into the mix. If someone met all three criteria and recognised the password, it was likely that they would panic and immediately set about trying to figure out how to get Bitcoin to pay off a blackmailer.

It was all rubbish.

Most spam detection systems now look out for the wording used in the email and recent versions are now sent as a picture of the text to avoid such filters, but they still circulate.

Two weeks ago, I got another phishing effort in my in-box and was duly impressed by the effort put into this one.

Apparently a notice of a debit to my account at FCB, with a visual reminiscent of the ones used by the bank in its advertising, it invited me to log in to the bank’s website to check on the transaction.

The sender email was genuine, using the actual FBC customer care email address.

My first reaction was to check my account using the bank’s app, instead of clicking on the link provided. There was no debit.

On closer inspection, the link provided did not go to FCB, but to another website dressed persuasively in the bank’s colours and design dress but would be harvesting your personal information to break into your account.

What would likely have happened afterward would be a series of small debits to the account over time that you might not notice for some time.

I provided FCB with a copy of the email and other pertinent information. In return, they blew my queries and requests for comment off with a rather casual “Phishing is a major issue for us (and [our] competitors).”

I got an email in FCB trade dress and it was relevant to me, because I do some banking with the institution. The same scam would work the same and look equally persuasive for any bank in TT, and indeed the world.

Online banking tips

- Bookmark your banking website and use that link to enter your customer space at all times. Don’t click on links in emails.

- Your bank won’t ask you to click on a link in an email to enter their website.

- Use the bank’s app to check your accounts online and ask whether connections are encrypted on the web or in the app.

- When in doubt, take the longer route to access your personal information online, complete with verifications.

- Trust nothing.