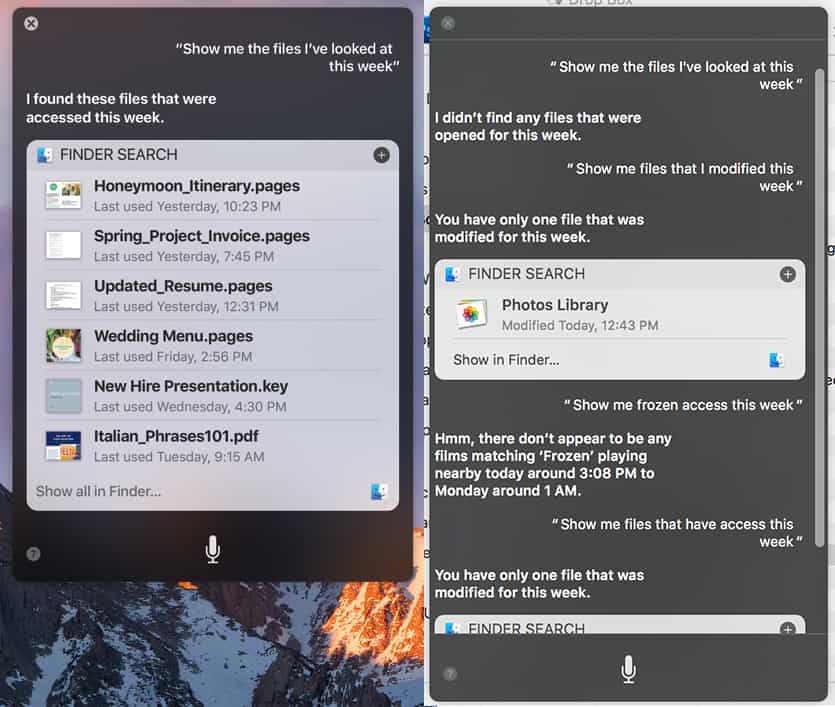

Above: In Apple’s halcyon world of Siri searches (left) you are a demon of productivity. In my Siri searches (right), I’m apparently looking at photos all day long.

BitDepth#1062 for October 11, 2016

Caption: In Apple’s halcyon world of Siri searches (left) you are a demon of productivity. In my Siri searches (right), I’m apparently looking at photos all day long.

There’s a clear linkage between the ambitions of Apple’s Macintosh operating system (OS) releases since it embraced Unix and the experience it expects its users to have with the product.

Early on, when the company was still early in its OS transition, it struggled with the look and feel of the graphical user interface (GUI), trying to marry the familiarity of the older Mac OS with the NeXT based OS it was being melded with.

As a way to woo users, Apple dubbed its new GUI Aqua, and did a lot of flashy interface things with display PostScript that made the new OS X a thing of liquid beauty.

Once the company ramped up the responsiveness of the OS, the company began a run of names that reflected ever speedier jungle cats.

The company has since set its sights on ever more solid outcroppings of igneous rock.

In quick succession, Apple has released annual major system updates named Yosemite, El Capitan and now Sierra.

The user experience tracks those names closely as well. A user running Yosemite or even Mavericks for that matter, isn’t going to find much that’s terribly different in the current release, OSX 10.12.

Unless you happen to own one of the systems that has been summarily dropped as supportable by the new release. My main workstation and server tower is a 2009 MacPro that certainly has the CPU and GPU horsepower to run Sierra, but is blocked by a software blacklist that simply makes no sense.

I can hack the current OS to run on the hardware, but if I was going to go to those time-consuming lengths, I might as well build a Hackintosh, a standard PC running an altered version of Apple’s OS.

But there are other reasons I probably wouldn’t want to do that.

In the last two weeks, my MacBook Pro, which does run Sierra, has mysteriously restarted itself twice for my own good while I’ve been away from my desk.

Apple has also been messing around with its virtual memory management again, and the changes haven’t been particularly good.

An aside about virtual memory. All modern operating systems have an operating mode which swaps data back to the hard drive when it hasn’t been used for a while and RAM is scarce.

Think of your office desk. Everything on the surface of it is placed within easy reach and can be accessed quickly. That’s the equivalent of data loaded into RAM, the fast and volatile memory that holds your active software and documents, usually between four to sixteen gigabytes worth of it.

Off to the side of your meatworld desk is a deep drawer with a hanging folder rack that you have to push back from your desk, open and rummage round in before you finally find what you’re looking for. You bring that stuff out and put it on your desk, next to you.

That’s the tangible equivalent of virtual memory (VM). Data that gets pushed to the hard disk and stored until you need it. If you switch to a browser with many tabs open, maybe for reference while you’re writing, as I’m doing now (I don’t remember Apple’s system releases by name), you will experience a momentary pause. That’s the OS loading the browser back into memory from a VM swap file.

As more and more computers switch from achingly slow mechanical drives to much faster solid state drives (SSD) and computers ship with more RAM (think bigger desk), those switch times diminish and for most users, disappear entirely.

Sierra seems much clumsier in how it handles swap files (usually around 1GB in size each) and really doesn’t like to see more than nine of them in play at a time, which may account for the prophylactic restarts I’ve been experiencing.

I do push VM memory management regardless of where I work, and it annoys me that Windows still seems to handle this so much better than the MacOS does.

Mavericks and Yosemite were also better at handling big VM swap files than Sierra does in this release version.

Still, users of recent Macs finally get Siri, though the AI’s scope of control is tiresomely limited on the desktop. On an iPhone, Siri can control almost everything that a user might consider valuable in a hands-free environment.

On the desktop, such ambitions are likely to be more specific and work focused. Siri had problems with my unfamiliar accent, which local users of any voice recognition software will have experienced.

Despite that, it seemed surprising that Siri didn’t seem able to find things I asked for after recognising the words I slowly and carefully spoke.

I could open an app, but not a new document in any software, even Apple standard software like Pages and Mail. Finder searches failed more often than they succeeded and Siri, overall, seems to need more hooks into what the OS can actually do when driven by a mouse or keyboard. A guide for framing requests for action would also be useful.

The AI, no doubt educated through heavy use by Trinis, is unbeatable at finding the nearest KFC, though.

Siri on the desktop has a lot of promise, but it’s almost entirely unfulfilled in its current form, except for asking the AI stupid questions, which is always good for a grin.