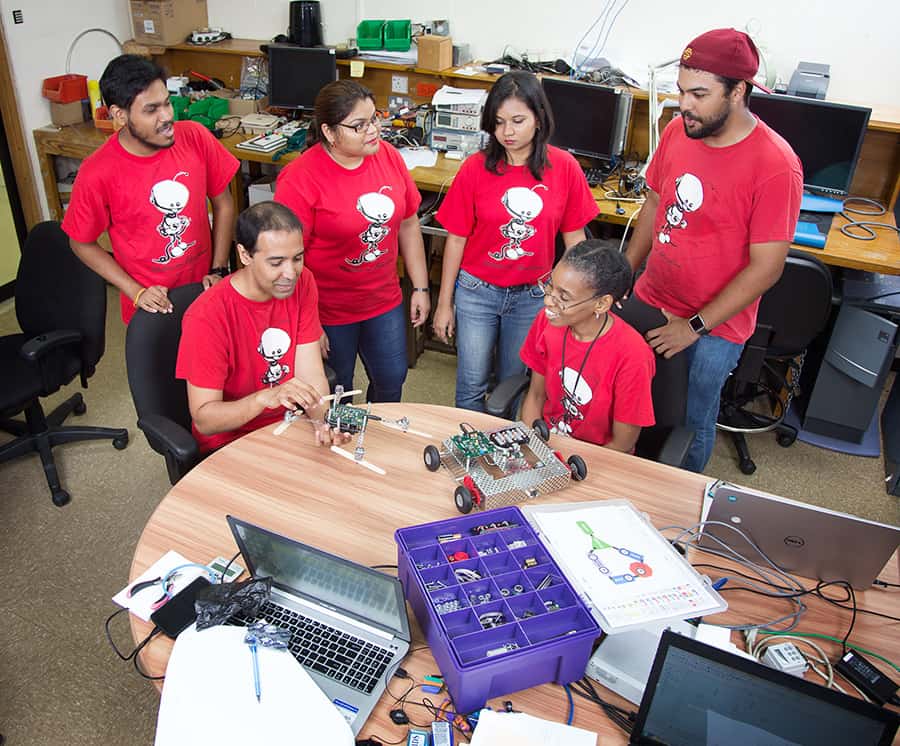

Above: The team that built the GadgetBox at UWI’s DECE discuss models built with the kit (purple box, foreground). Seated at front, Jeevan Persad and Cathy Radix, behind them, from left to right, Shivan Ramdhanie, Linda Sirju, Christin Parma and Daniel Ringis. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1060 for September 27, 2016

“The first thing that someone learns in programming,” Jeevan Persad said, “is how to make a computer say Hello World.”

“In embedded systems, the task is to turn an LED on and off. Usually when that fails, the solution is usually to be found in speed. The LED did turn on and off, it just did so too quickly to be perceived. Then you learn about delay.”

For most of the ten-year life of the entrepreneurial project, Persad and Cathy Radix have been relearning that lesson, along with new, off-curriculum electives in patience and determination.

Cathy Radix is a lecturer in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of the West Indies (DECE) and Jeevan Persad is a research technician.

Both have a deep and abiding belief in the learning potential of an implementation robotics in the primary and secondary school system, though they don’t come to it from exactly the same point of view.

They are not the only people in T&T, or indeed in the regional school system who see that potential, but they are among the first to propose a radical and practical rethinking of how it can get done.

Their mission wasn’t originally to build and sell kits of robotics components – the Gadgetbox product they are working toward building notwithstanding – it’s to get students more involved, at an early age, in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), the key quadrants required for the building of a technologically capable modern society.

“The Caribbean always seems to be playing catch-up,” Persad said, with a notable furrow in his brow.

“The first conversation about technology was about access to the Internet. Now it’s about being able to code.”

“But students say that science is hard. Math is hard. Physics is hard.”

“But there’s also a moment when someone intersects with computing or engineering principles and just gets it, it’s a successful technology intervention and the spark is fired.”

Over the last ten years, and more intensively in the last five, Persad and Radix have been involved in the conversations around how to change that through learning processes that are more engaging in the class room and robotics has emerged as an excellent option for changing an intimidating status quo.

“I’m more of a professional educator,” Radix said, “I’m learning how people learn and teacher awareness exercises suggest that demonstration is good, but hands-on participation is best. Unfortunately, the equipment is expensive.”

“Class times are often too short for participation and availability, mentoring and support are key to success in any hands-on initiative.”

Early classroom robotics project training was based on existing packages like Lego Mindstorms, but cost and fragility in a classroom environment quickly became an issue.

Most existing robotics packages also require a computer to run the project, which means power, computers and IT staff for a classroom and all those supporting elements aren’t always available.

There are currently at least 12 ‘Robotics in the classroom’ projects in various stages of startup and implementation in T&T as part of the Tech ED curriculum for schools.

When a kit in the classroom costs US$300, the overriding concern becomes ‘don’t break it.’

“But breaking is part of the learning and discovery process,” Persad explained.

“We really tried our best to buy a kit,” Radix said, “we tried all of the retail outlets, we spoke to Unesco’s kit supplier, giving them kit specifications and requirements. It couldn’t be found and it couldn’t be easily put together.”

So Persad and Radix, with the help of past and present students of DECE, built their own.

It’s called a GadgetBox and there’s a fundraising campaign for its construction running for the next two weeks on Indiegogo.

The unassuming kit is a plastic box with segmented cells in a tray you lift out with a collection of larger support components below.

If you’re a person of a certain age, it looks like a Meccano set with wires and integrated circuitss, and it’s meant to be equally resistant to youthful vigor.

While Meccano is making its own foray into robotics, like most packaged robotics systems, it’s designed to build one thing. The Gadgetbox may look raw, but it’s meant to provide raw dough for play and inventive discovery of almost anything.

“Cathy brought an opensource philosophy,” Persad said, “my own background is in understanding how things are put together.”

The computing part of the equation was eliminated entirely in favour of the computing device available to most of their potential audience, a smartphone.

“This was an opportunity for us to design something made for the Caribbean and also made there,” Persad said.

The demonstration kits use punched metal construction plates prepared by local electrical firm TYE and run on a logic board designed by Persad. It’s an integrated board, with all of the contact points that a budding engineer might need and runs Gadgeteer, an opensource .NET framework from Microsoft.

Programming is done using distinct coloured blocks printed on paper that the young programmer cuts apart and arranges in logical strings. A photo of the layout of code components represented by the paper layout is processed by the smartphone software (currently for Windows Phone with a port to Android scheduled)which identifies the blocks and turns it into code strings, which are uploaded to the GadgetBox logic board via Bluetooth. Up to 99 of the code blocks can be strung together and branched to make algorithms.

Radix and Persad have found themselves in an interesting space with a product that demands pure entrepreneurship to stand any potential for success.

The education system isn’t designed for speculative business propositions vested in a retail product.

All of the money available for development is designated for either products with a known customer base or for pure research and the GadgetBox is about to move from being an idealistic concept to a practical product competing in an unknown marketplace.

“We have to answer the comparison question,” Persad said, “how to we know that this is equivalent or better value than a commercial alternative?”

The key answers are two-fold. Ruggedness and price. Radix and Persad have spent around $120,000 getting the project to this point.

The projected price of the GadgetBox hovers around TT$300 and the device is made up of robust metal, so it’s suggested for children nine and older. Public availability of the kit is planned for December 2017.

The logic board can connect to standard electronic parts and users with access to other components may have success pulling bits out of discarded devices. The motor control board on most junked printers, for instance, might find a second life controlling moving armatures in a GadgetBox project.

“We wanted the GadgetBox to be something that could be affordably added to a booklist, a device that students could work with on their own,” Persad said.

“We designed it to be friendly with everything, Raspberry Pi, Arduino, Vex, Mindstorms and cupboards full of old electronic parts. Everything.”