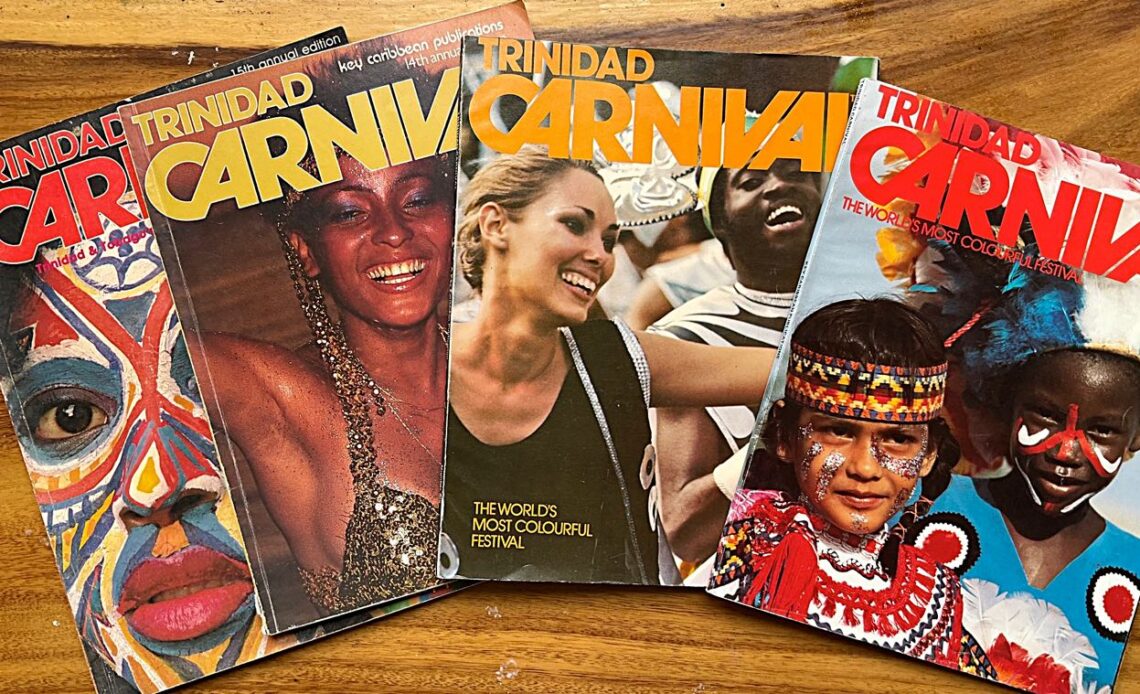

Above: Covers of the magazine published in 1987, 1986, 1978 and 1979. Photographs of the magazine and its spreads are by Pat Ganase from her personal collection of the publication from 1974 to 1987.

Pat Ganase kindly responded to my request to tell the story of Key Caribbean’s Trinidad Carnival, the defining magazine chronicling the national festival between 1973 and 1987.

The first issue of this magazine was published when I was in fourth form at Trinity College (her brother Chuck Wong Chong was a classmate and friend), so it effectively predated any inkling that I might be participating in the documentation of the festival.

By the time I was in the second year of sixth form and aggressively considering some kind of career in journalism, the benchmarks of high-end publishing were Trinidad Carnival and Owen Baptiste’s People magazine (prefaced by the word Caribbean in small print).

I’d have some small success selling stories and photographs to Baptiste, but would only ever have one photo published in an issue of Trinidad Carnival and then only because I had a photo of a costume that they needed.

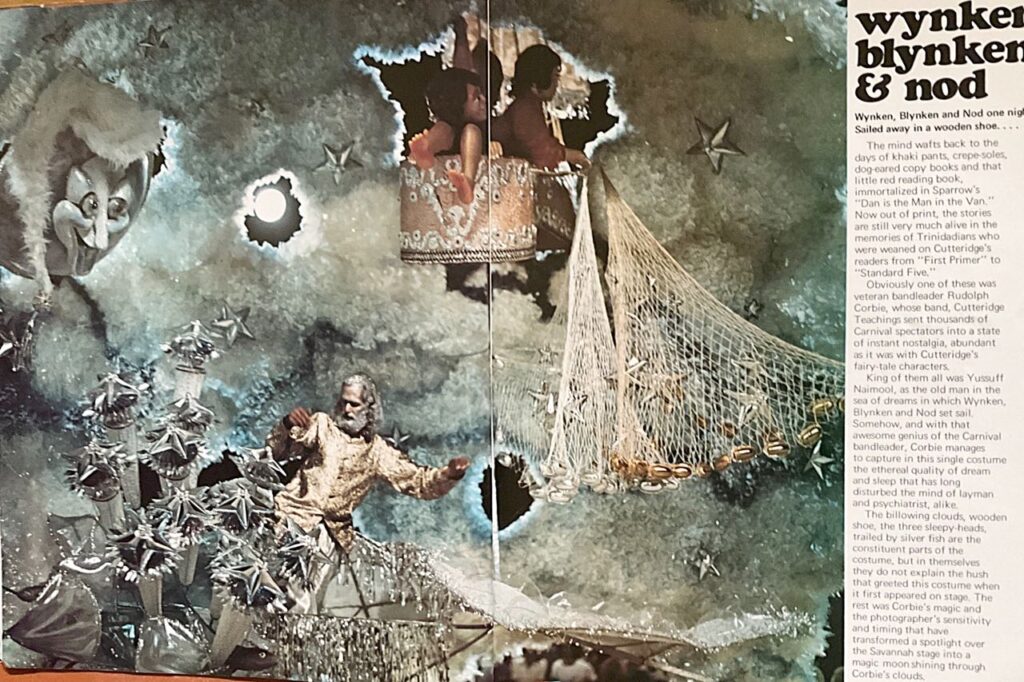

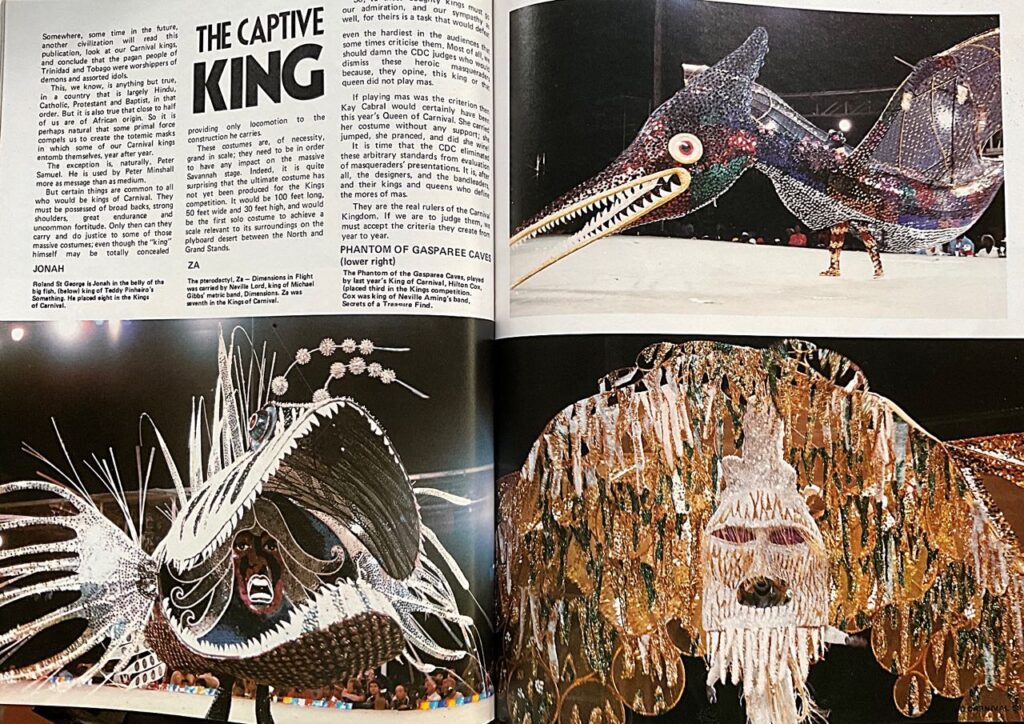

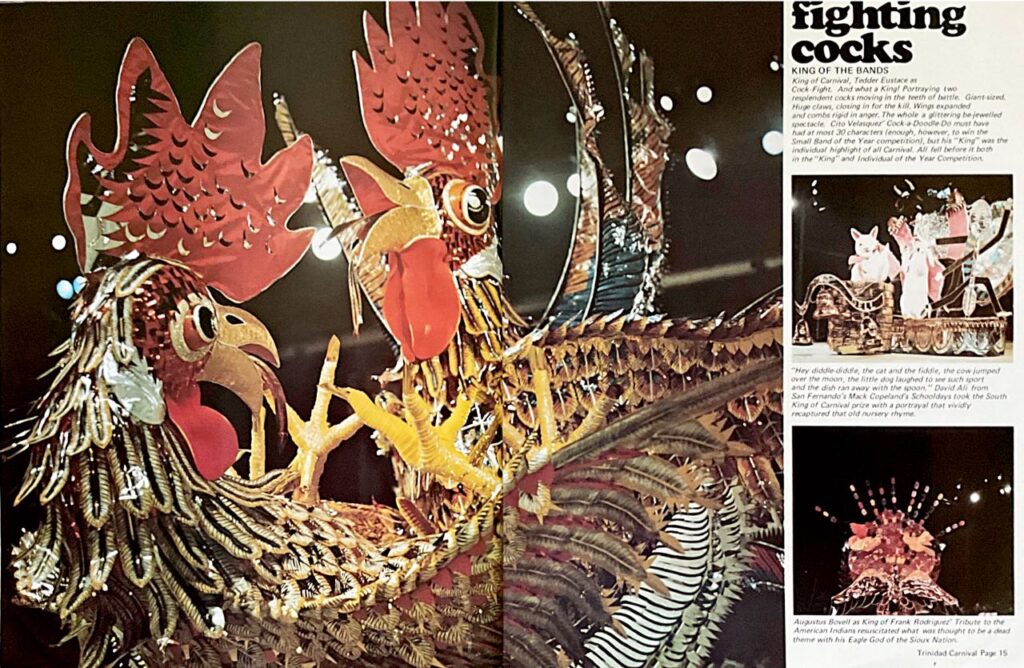

Over the last five years of the magazine – my first five in the Queen’s Park Savannah taking photographs – Pat Ganase and Roy Boyke, a former Express Chief Photographer, were present. Boyke would always stake out unusual angles and photographed King and Queen of Carnival costumes with a Pentax 6 x 7 camera, a DSLR shaped howitzer of a camera that captured medium format transparencies that made all the difference on the pages of the magazine.

Looking back at the magazine across three and a half decades, most of them commanded by dramatic revolutions in desktop publishing, the typography in particular is painful to see, but the photos and the writing always transcended any production limitations and the collective work remains this country’s most consistent and considered effort at understanding Carnival and giving it context from a journalist’s and documentarian’s perspective.

But this is Pat’s story. Asked for a biography, she responded with the line, “Pat Ganase is a writer. She played mas as a blue bird in 2020, Mas Pieta.“ This is her insider’s knowledge of how the magazine Trinidad Carnival came together. It is an important recollection of this crucial intervention in intelligently engaging with the annual festival.

– Mark Lyndersay

Trinidad Carnival magazine was published by Key Caribbean Publications from 1973 to 1987. It was subtitled “The world’s most colourful festival” until 1984. In 1985, the subtitle was “The world’s most exciting festival.” In 1987, the 15th edition saw a change to a larger format, subtitled “Trinidad &Tobago’s unique festival of Mas, Pan, Calypso.”

I returned from the USA in September 1973, armed with a Liberal Arts BA from Hollins College Virginia (1970-1973). The first job offer came from Bishop’s Centenary College (St Cecilia’s) to teach Literature; classes were in the morning so it was a half day job.

The impressive 1973 first edition of Trinidad Carnival was in bookshops and I also applied to work for the publishing company. I was hired as a free-lancer in the afternoons.

The magazine was a vehicle for photographs almost entirely from the portfolio of Roy Boyke, who had a passion for Carnival. Over the next 14 years, the annual Trinidad Carnival grew from this perspective as he enlisted other photographers, writers and artists.

The company, Key Caribbean Publications, had been set up by directors Roy Boyke, Erica Williams and Ram Kirpalani to publish Patterns of Progress, (1972) a collection of essays on the state of the nation ten years after independence.

Then Prime Minister Dr Eric Williams wrote the lead article. Through a Maze of Colour by Albert Gomes was in production. Homemaker and Tempo (BWIA’s inflight magazine) came out once or twice a year, trying to be quarterly.

Companies could subscribe and receive copies of Trinidad & Tobago Today, an annual pictorial diary, to gift their customers and suppliers.

I joined Key Caribbean as a proof-reader and intern. In 1974, Key’s editorial department was headed by Keith Smith for production of Trinidad Carnival.

I witnessed Shadow on the Grand Stand stage, and went with Keith to interview him in a tiny house at the top of Mt Hope. Thus began my thrall with mas, our unique culture of magical transformation, music and pan.

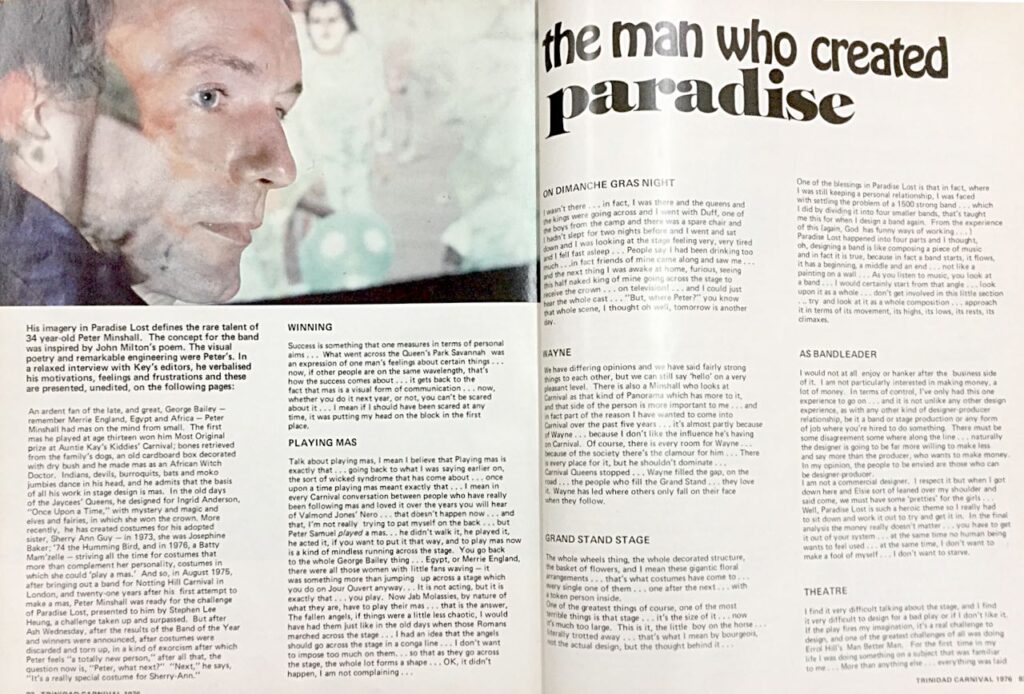

I felt lucky to be teaching in the school that Sherry-Ann Guy attended so I could “interview” her. Peter Minshall’s costume, From the Land of the Hummingbird which Sherry-Ann played, was the most significant marker of that year.

This shy self-effacing petite girl in the first form was the queen of that carnival, the individual that marked the turning point of Minshall / not-Minshall mas.

By 1975, I was full-time with the publishing company. Carnival research – surveying mas camps, listening to the season’s calypsoes, panyard visits – would begin in January, but the “real work” – photography, captions, reviews – would start in Carnival week.

Roy pushed me to meet the makers in the mas camps and musicians in the panyards, mostly in East Port of Spain, mostly after hours.

It was an immersion in Trinidad and Tobago culture, my place in it, and the grandest education about who we are as a people.

The 23-year old me was entirely in tune with what Roy wrote in the 1975 editorial as the spirit of the annual carnival: “…this unique celebration of life in which an entire society removes its mask and finds revealed not simply hedonism but rare and priceless truth; warm pervasive love and poetry released in song and dance and laughter.”

The Technology

The typesetters – Roma Jules and Eleanor Cyrillo – worked on IBM Memory typewriters, outputting text to specifications (font, size, spacing, column width) on a chalk-coated paper that would be cut and pasted (using wax or glue) onto design flats that were facsimiles of actual pages.

Each page flat featured areas for photos which were selected as film positives (35 mm or 120 mm slides). Text areas had to be precisely positioned since the flats would be used to create page negatives.

The designer from 1974 to 1977 was Arlette Johnson. The Art department was a team of paste-up artists handy with Xacto blades, the wax machine and photocopier; each with skills in illustrating or drawing, and dreams of being a graphic designer.

Thousands of photos were collected in a Carnival season. The photographers were issued slide film; Ektachrome ordered in bulk from the agent, JN Harriman’s. For some coverage in black and white, we used Tri-X which was processed in-house.

There were special arrangements with slide film processors. Batches of exposed film would be delivered to Holly Chong or Gary Chan to process overnight.

On the Carnival Monday and Tuesday, batches were dropped off at specific intervals so the photographers and editors could review the film by the time the sun went down and they came back to office.

In the intense two weeks, we subsisted on takeaway food, mainly from Chinese restaurants in the area.

After 1974, the magazine went to New York for pre-production and printing where their turnaround to finished magazines was faster.

The package of page flats and slides would usually be despatched with a flight attendant on BWIA on the Sunday after Ash Wednesday; the publisher or editor would follow a few days later to start looking at output from the lab.

If all went well, that person would return with advance copies of the magazine.

The Savannah

It was day and night work in the month the Carnival magazine was produced. By day, I would plead with Prince Cumberbatch at the Carnival Development Committee for accreditation and passes for the CDC shows; with whoever was President of Pan Trinbago for the Panorama events; and with managers of calypso tents for passes for photographers and reporters.

They all assumed we wanted to see the shows for free. I had the feeling that people thought that making a magazine was not real work. Night-time was for visits to mas camps and panyards and the competitions and shows.

Getting stageside in the Savannah was a singular challenge. Even with passes, it was hard to get past the unofficial gate guards. Mary Norton was my mentor and patron, saving me a seat on the small bleacher set up for photographers.

We looked out for each other, sharing drinks and sandwiches, and a running commentary on the mas.

We looked on in awe and hugged each other when Peter Samuel struggled to get The Serpent to lift its head in the preliminaries of the Kings competition in 1976 and were jubilant when he danced his way to the King of Carnival on Dimanche Gras.

1976 was the year that Minshall lifted mas to poetry. Keith visited the Lee Heung mas camp that year and couldn’t stop talking about Paradise Lost, the designs and the emerging costumes.

1976 was trend-setting not only for the mas, but for the magazine. The Trinidad Carnival was largely a photo-documentary, with reviews of pan and calypso.

It was the first year that a masman would speak about his process: Minshall set out his thesis of a band. Keith Smith left the company that year, going to help Owen Baptiste build People magazine.

The Contributors

I was constantly astounded by stunning photography captured from shows and the street. I aspired to provide texts that would complement the photos, and learned to write what was not obvious in the photos.

I also learned that information about bands, designers, lyrics, steelbands, arrangers and calypsonians had to be collected live, in direct research, listening to radio, and from the network of people inside the mas, pan and calypso.

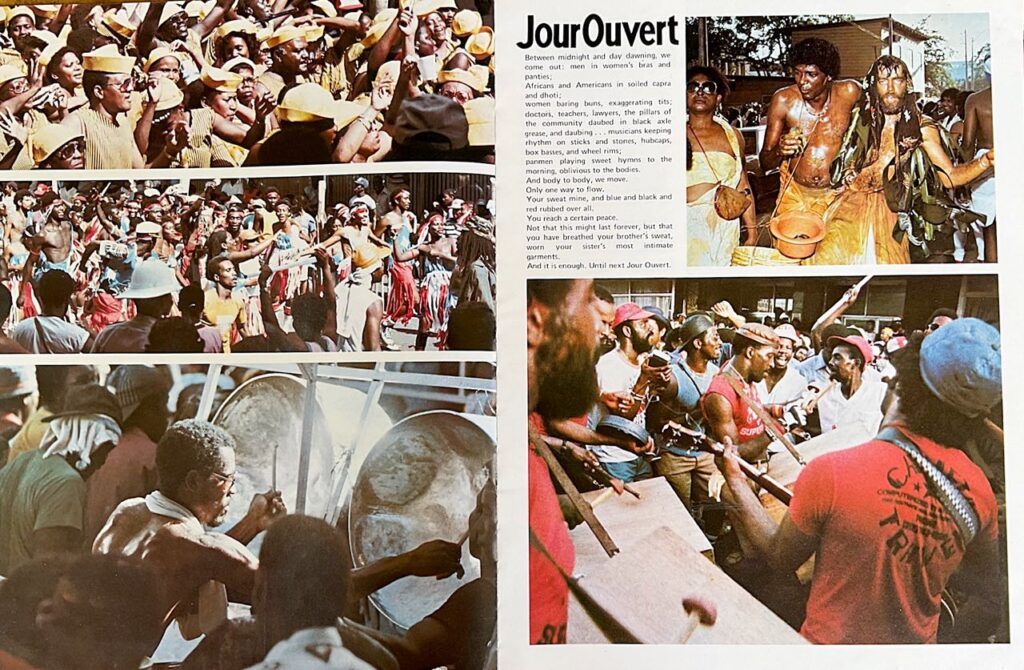

In 1979, there was no Panorama as steelbands boycotted CDC shows spelling a J’Ouvert almost without pan.

Roy continued to cruise the streets with his camera, capturing portraits, evocative plays of light and dark, focus on a face or a wining bum bum; the frenzy of pan audiences, and the most miraculous early morning light creeping through a rack of bass pans on Independence Square.

In his editorial, Folk Festival or Show Business, he wrote that the continuing miracle was that “a cast of thousands is still prepared to go on stage in pure traditional celebration …. of life itself.”

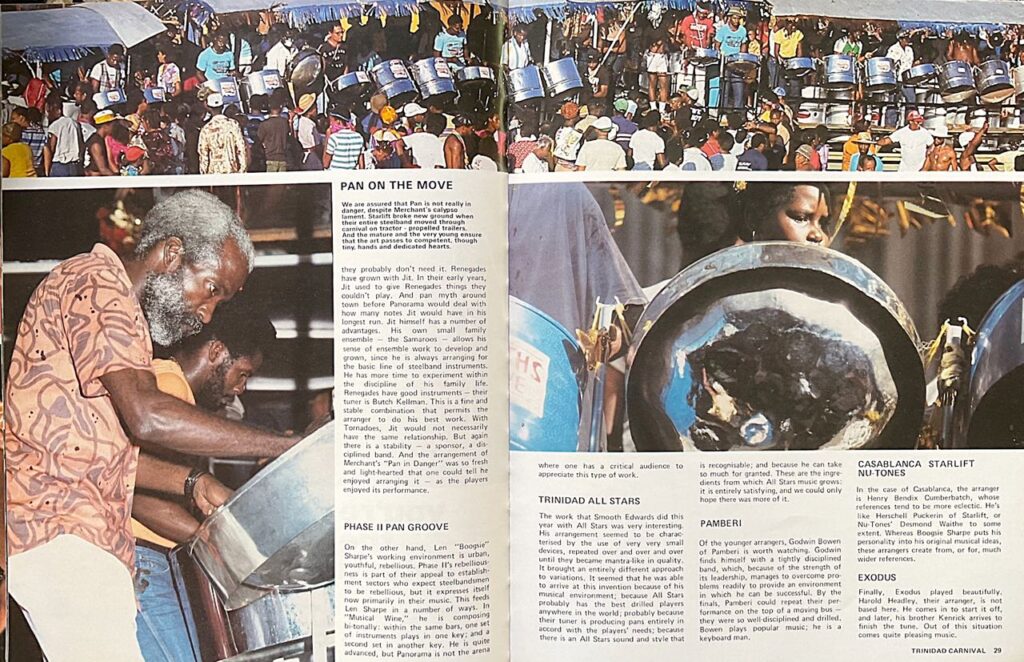

We attracted talented writers to cover specific areas: NY-based Knolly Moses on Pan; Pat Bishop on Mas, Calypso and Pan; Suzanne Robertson; Valerie Taylor; and Therese Mills as super editor.

Fleeting conversations and insight bonded us into a special tribe of observers, even if we met just once a year.

Occasional features came from Michael Anthony; Selwyn Ryan, Elma Reyes. Earl Lovelace previewed his Dragon Can’t Dance in 1977; and Leroy Clarke wrote his philosophy on Masks and Mas.

Many others came on board for research, illustration, photography, commentary or just to be extra hands in a season when “many hands make light work.”

From 1981, the production of the magazine settled into a Carnival rhythm, ramping up with the season through pan, calypso, kiddies, jouvert, parade of bands and accelerating to a las lap. Photographers were Roy Boyke, Garnet Ifill, Ranji Ganase and Monica Barry; all film was processed in-house.

Our las lap was the Sunday after Ash Wednesday; no one slept more than a couple hours on the nights before the magazine was put on the plane to New York.

Print quality seemed to take a leap forward in the early 1980s. A special issue was created in 1982, the tenth anniversary.

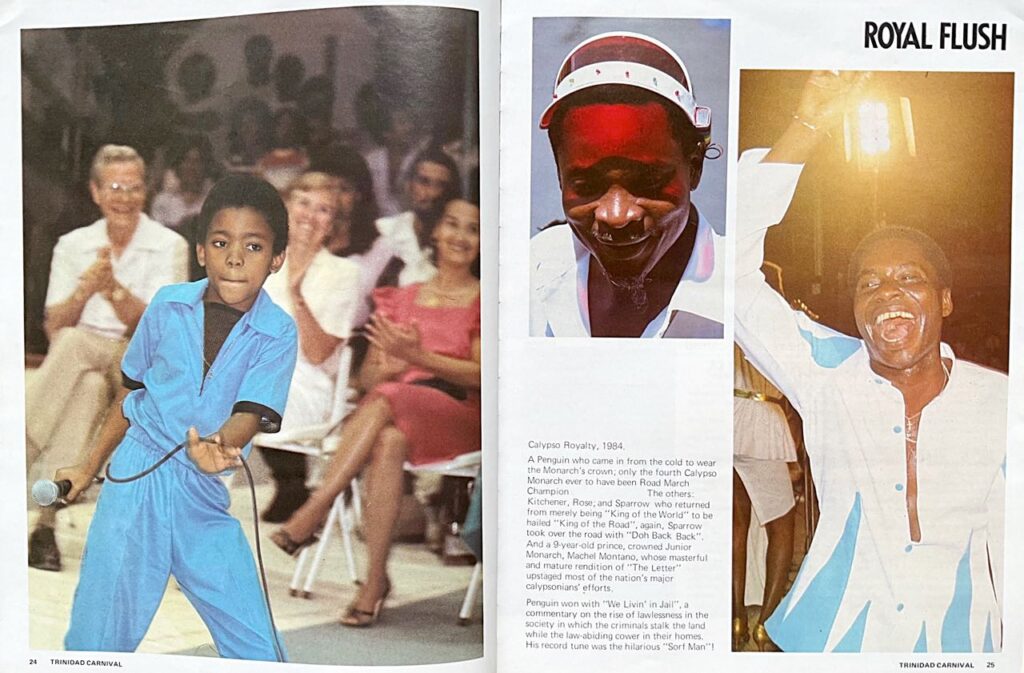

In 1984, nine-year-old Machel Montano was Junior Calypso Monarch, Minshall was brewing his Callaloo, and I, greviously pregnant, trailed Suzanne Robertson through the Grand Stand looking for a clean restroom.

Two years later, with King David Rudder, the Young King, Calypso Monarch and Road March winner; and Machel Montano again Junior Monarch in diapers with Too Young to Soca, I would be looking still.

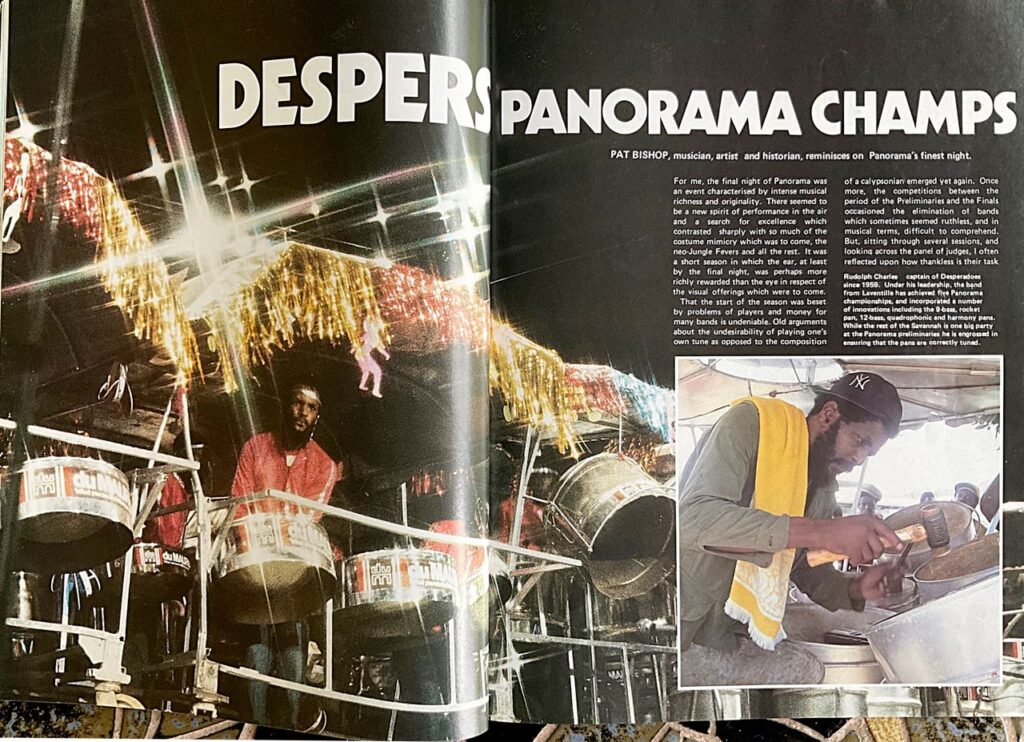

In the 1986 editorial, Roy Boyke recorded the passing of two heroes since the last Carnival: “From Indian and from African stock they had come; one a Hindu, the other a Catholic, both to add lustre to the glory of steelband; one with a hammer in his hand; both with humanity in their hearts.”

Rudolph Charles aka “The Hammer,” was the iron strength of Desperadoes, a man who could “pong a pan…or a stupid man.” Ram Kirpalani had been the silent steady patron of the Trinidad Carnival magazine; Kirpalani’s was the sponsor of the Pan is Beautiful music festivals of 1980, 1982 and 1984.

At Carnival 1987, the new coalition government of ANR Robinson was in place.

The country was hopeful; we would survive the major devaluation of our currency, mass retrenchments and economic depression.

Perhaps it was this hope that encouraged the Trinidad Carnival magazine to a more substantial format: 9 inches by 12 inches up from 81/2 by 11.

With updated masthead and contemporary layout, this issue felt spacious and open to consideration of its photography and commentary.

But too many other things were not in its favour: labour-intensive, time-consuming technology, a deepening recession.

I left to raise two infants; and the company down-sized.

Over the years the magazine was in constant dialogue with the society, with those who loved mas and all the voices wanting better for the musicians, makers and players.

Through the magazine, you could chart the trends, anticipate a direction. Since then, a generation has grown up with different ideas of self and society.

And in 2023, after covid-19, who knows where the Carnival might go? Controlled or wanton? Inclusive or exclusive? Will it take back power in protest? And who will record it?

By the time I got a job at the Guardian after the coup in late 1990, barely three years later, the publishing world seemed to be reset: computers bridged the gap from story input to desktop publishing; and the Guardian’s Carnival souvenirs were on the street on Ash Wednesday.

The Trinidad Carnival magazine was never a commercial success. Specialist salespersons would sell advertising; Roy with his marketing hat, dev ised strategies to entice advertising in support of Carnival images.

The print run was never more than a couple thousand; and subscribers even at $20 a copy numbered in the hundreds; most people wanted it free.

I remember being in the Kirpalani’s department store, and seeing the store clerk ripping pages from past issues to wrap glassware. I cringed to think that our priceless record – indeed the nation’s unique mas culture – was so little regarded.

Alongside the annual Trinidad Carnival, Key Caribbean Publications produced many other print items: annual reports, promotional brochures, other magazines and books.

The in-flight magazine, Tempo, became Caribbean Beat – enjoying a longer running history and sustainability through distribution on BWIA/CAL’s network – from the publishing company that Jeremy Taylor founded.

But the Trinidad Carnival magazine was never replicated: Roy Boyke was a visionary, ahead of his time; he went on to be the advisor to many political parties heading to government around the region.