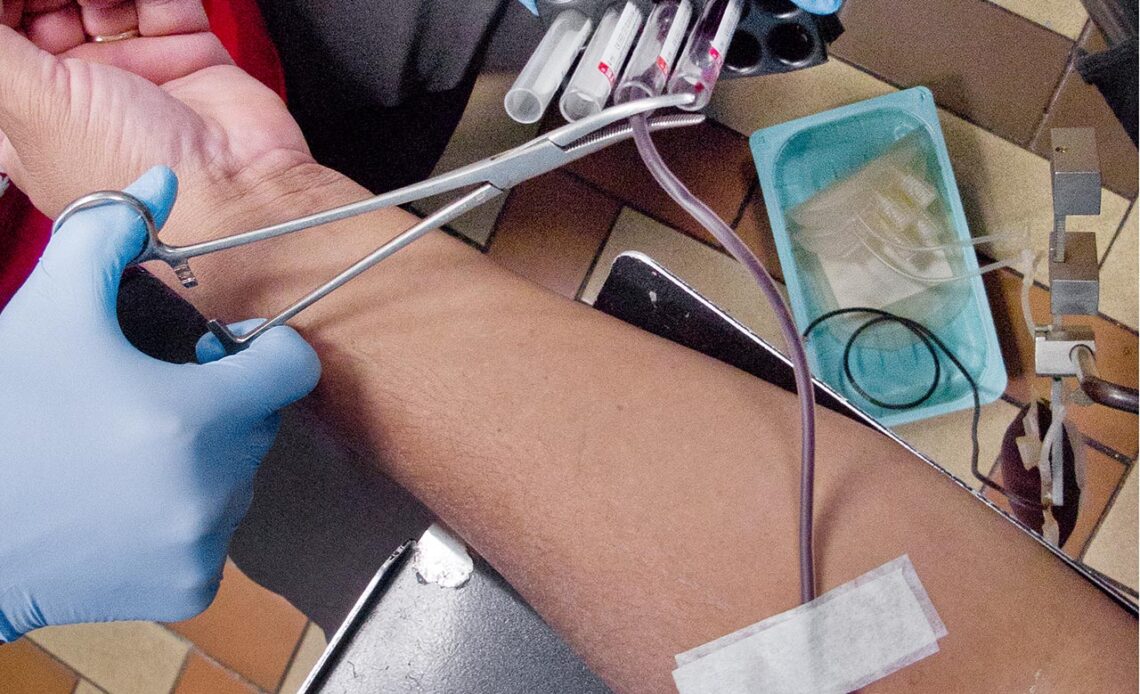

Above:Four vials of my blood are taken for testing to verify its fitness for medical use. Blood lubricates the most critical parts of the health sector, and it’s the one key medical element that’s best given freely. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#789, originally published on July 05, 2011.

Last week, I donated my 16th pint of blood, finally hitting a personal goal I’d set for myself in 2002. The occasion seemed as good as any to finally pull the trigger on this column, one that I’ve been trying to gather information for over the last three months.

For an organisation that’s trying to sort out a real challenge with blood donations, the Ministry of Health remains shockingly hostile to even openly supportive efforts to tell a story about blood donation.

I proposed a story to the Health Ministry about the science of blood, partly because I felt invested in the business of blood donation, partly because I was curious about what had happened to my first 15 pints of blood and partly because it seemed sensible to put some straightforward reporting into the public domain about the work of the National Blood Transfusion Service.

What I encountered was a kind of disengagement from reality, as people who were quite aware of the real issues with blood donation and the risk to the health system it posed, fell back on the Ministry’s rulebook for the media and quietly stonewalled me on the story.

I really wanted to see the laboratory where blood is prepared and to take some photographs there, but that never happened because that sort of thing isn’t allowed.

In January, the Ministry of Health summarily and with no communication to the public, banished a decades-old, well-understood chit system and replaced it with a World Health Organisation endorsed system of altruistic blood donation.

That decision created a situation of entirely predictable chaos, as people who had been “saving” blood found their accounts effectively emptied and the entire architecture of the blood “bank” fundamentally changed.

The first five pints of blood I gave were, in my mind, a health investment. Blood given for when I might need it. The next nine I gave because it became so easy to do. What’s missing from the Blood Bank now is a readily shared message that will take people past the banking metaphor to a fresh and inspiring rationale for blood donation.

What happens to a pint of blood is an impressive narrative that details the healing power of donated blood, but it’s not widely known.

That message should be hallmarked by some simple characteristics.

It should emphasise the positive result of blood donation. One person at the Blood Bank quietly came to me during my visit there and explained what happens to a pint of blood.

It’s an impressive narrative and the healing power of that blood, after it’s separated into platelets, packed cells and plasma goes well beyond most people’s perception of donated blood simply moving from one vein to another.

The National Blood Transfusion Service should commit to greater public transparency in its operations. Blood is as personal as it gets, and sharing it demands a shared sense of mission. Shrouding the operations of the service under unnecessary layers of secrecy does not promote engagement or enthusiasm. It just makes the whole process seem medieval.

Leverage your existing donors.

People who give blood can be positively evangelical about the experience. They can tell you what’s working and what isn’t with the service and will champion and broadcast your cause. This column is an example of exactly that.

More people will give blood at work or in a shared social experience than will ever come to the service’s offices. Former Health Minister Therese Baptiste-Cornelis’ announcement that there will be as many as five more mobile units put into operation is commendable, but it will require more of the same kind of planning that didn’t go into the abolition of the chit system.

Buying vehicles outfitted with equipment is the easy part.

Training a team as effective as the one that’s currently doing all the work of mobile blood gathering will take six months for practical knowledge but will require years of coaching to attain that team’s level of social engagement and repartee with donors.

The existing mobile unit, who I’ve come to know quite well and to admire over the last nine years, draw blood with their hearts and wit, not with their needles.

What happens to your pint…

After a pint, or unit of blood is gathered, four vials of blood are taken as well. An additive is placed in one to prevent clotting, and the other three are tested for potential contaminants. Tests for HIV and Hepatitis B take up to four hours.

The unit of blood is taken to the laboratory of the Blood Bank, where it spun twice in a centrifuge. The first spin separates the red cells and plasma. From this, 300ml of red cell plasma, called packed cells and 200ml of plasma are separated.

What remains is spun again and 50ml of platelets are taken from what’s described as a heavy spin. The remaining plasma, usually around 150ml, is frozen. The entire process must take place within eight hours for the blood to be viable.

After the process is done, the bank will have 50ml of platelets, which will last for up to five days, 300ml of packed cells, which can last for 35 days and 150 ml of frozen plasma, which can be kept in that state for up to a year

A patient who is bleeding will need packed cells, if there is heavy bleeding or dengue that patient will require platelets if their condition becomes critical. Plasma is used with burn victims to boost their healing factor, and heart patients will require all three.

Plasma is also used when critical volumes of blood are lost, and healing factors are compromised.

Among the changes that the Blood Bank is implementing is the disbursement of blood according to evaluated patient needs, which came into conflict with the chit system.

Blood is required regularly for chronic renal failure patients, most of whom have long exhausted their pool of potential donors and for patients requiring transfusions.