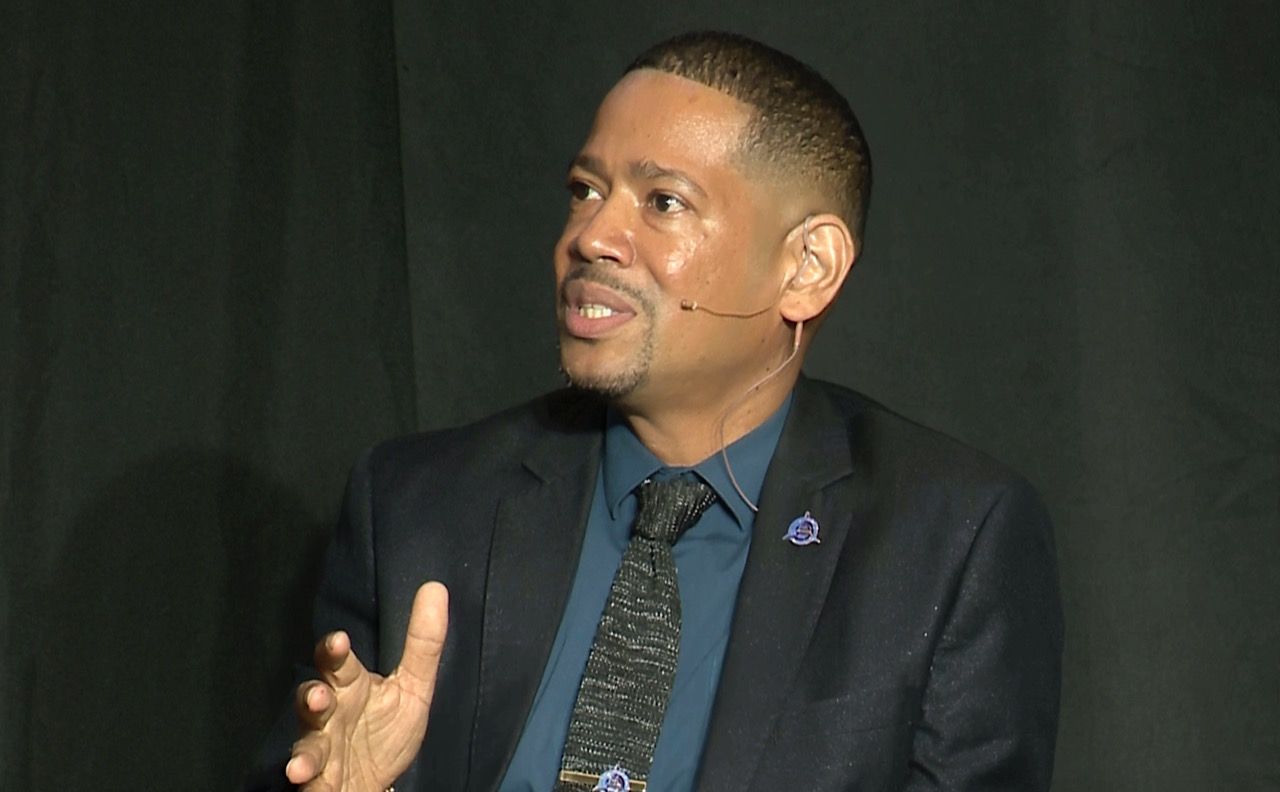

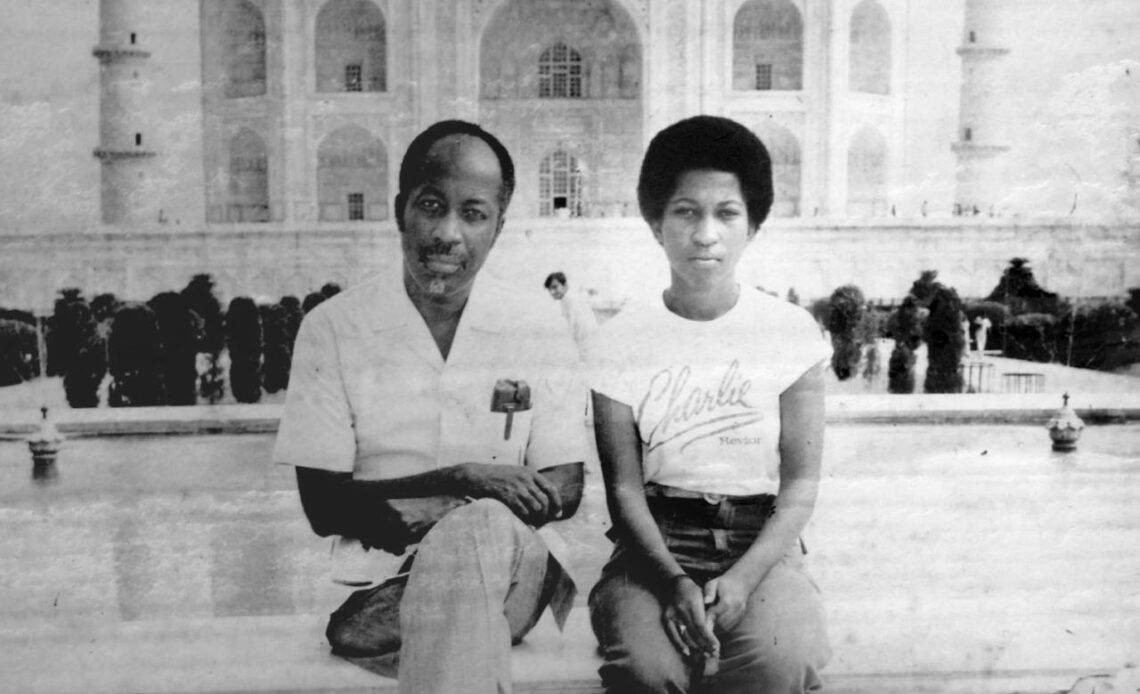

Above: Reginald Dumas and his daughter Sonja at the Taj Mahal.

BitDepth#1450 for March 18, 2024

When Reginald Dumas passed away on March 07, Trinidad and Tobago collectively lost a champion for good governance.

Mr Dumas spent most of his life first learning the workings of the public service – primarily in its diplomatic corps – and then vigorously trying to steer it back to more effective ground.

For decades, the effective authority of the public service and its managers has been quietly eroded in the name of reducing bureaucracy without any matching enthusiasm for introducing the kinds of checks and balances that the service’s bureaucratic processes were meant to offer.

The word bureaucracy, like the word amateur, has been distorted over time through repeated reference to the negative aspects of its existence.

The word amateur, derived from the French amor, simply means, at its root, to do something purely for love.

Bureaucracy was coined to describe a system of government that separates policymaking from execution, providing a buffer between those who direct and those who oversee day-to-day practice.

Once the rules and guidelines for a bureaucracy have been put in place, the expectation would be that it would deliver services, in the case of the government, to Trinidad and Tobago’s citizens.

The characteristics of a modern bureaucracy are a clearly defined hierarchy, continuity of employment within the administration, impersonality through adherence to established rules and procedures and the development of expertise, through an administration chosen by merit and continuously trained.

That was the form of the Colonial era public service that Reginald Dumas joined in 1959. After 1962, only the ambitions changed.

The public service he retired from had drifted far from even those post-Colonial dreams, and he never tired of trying to bring the service back to those early principles.

In recent decades, successive governments have worked more purposefully to subvert and diminish the oversight of the public service, creating special purpose companies and agencies to execute government policy without the encumbrances of all those troublesome rules and procedures.

Generally that hasn’t worked terribly well and some of those agencies have collapsed in a blizzard of fraud allegations.

After writing a column about the problems that the public service was having with digitalisation, a project that actually reaches all the way back to the first National ICT plan introduced as Fast Forward in 2003, Dumas reached out to me.

His initial curiosity was about an August 2022 column, Why public sector transformation fails.

At first, he seemed to be clarifying in his own mind some of the issues that digitalisation raised for the public sector, but then he began to explain why some of those issues existed and the challenges that were embedded in the way it is organised today.

It was one of those phone calls I wish I’d recorded, because Dumas then proceeded to give me a 90-minute master class in the history, intent, reality and difficulties involved in the formation of the modern public service.

I’d asked a few questions as he spoke, and he promised to get back to me “After I dig around under the house.” That’s apparently where he kept many of his reference papers and documents.

He called the very next day with further clarification and with additional information he hadn’t recalled off the top of his head.

“You know,” he told me as I made additional notes, “if you write this, they [senior public servants and ministers] will know I told you.”

There was a moment’s silence on the phone, and then he said, “Yes, go ahead.”

The resulting column appeared on October 24, 2022, and even at twice the length of the Newsday print version, it barely scratched at the insight that Reginald Dumas granted me during that afternoon call.

His family, after suffering the initial sting of their grief, should ensure that the trove of documents he kept under his house is managed carefully.

My secret hope is that he had a manuscript in progress that reflected the decades of contemplation and thought he invested after his formal service.

The many thoughts that leaked out in his columns, letters to the editor and statements to journalists suggest a larger manifesto for public sector evolution.

He might have retired from the public service, but it was never far from his thoughts.

I imagine a TT where those in power recognised the quality of his thinking, the depth of his experience and his enthusiasm for a better way and created a way to harness those assets, even when they were politically unpalatable.

That would have required a fearlessness, equanimity and passion for development that matched his own and as Reginald Dumas knew very well, that’s remained scarce in local politics across the board.