Above: The original mask. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1407 for May 22, 2023

It was even stranger, just over three years later and at the end of it all, to set the mask aside than it had been to put it on.

After the initial breathlessness and fogged spectacle lenses, to walk into a store, or approach a group unmasked now feels naked, like a dream of showing up to school having forgotten to put on trousers.

The original two cloth masks, still with their terrycloth inserts, still hang on the wall behind me.

Long replaced with proper KN95 jobs, I’d considered sending them to the frame shop to be properly immortalised for their role in getting the family from there to here.

Then I’d stop and wonder if that wouldn’t be pulling the devil’s toe, indulging in hubris and overconfidence even if almost everyone had chucked their masks.

Covid was fierce in my circles. Both of my siblings in the US were infected. Among my secondary school classmates, a shrinking group of around 35, three died from the virus.

So I have little patience with covid deniers, who are entitled to their opinions, but not my audience.

Carnival 2023 seemed like a good benchmark to gauge both the pervasiveness and strength of the virus.

The event ended up being the mother-in-law of all Carnivals (some unkind souls used a foul maternal invective to describe the celebration) but it also acted as a bellwether on the status of covid19 in Trinidad and Tobago.

So I sat out this year’s festival, not out of the occasional disinterest and petulance that’s haunted my feelings about it prior to 2020, but out of caution.

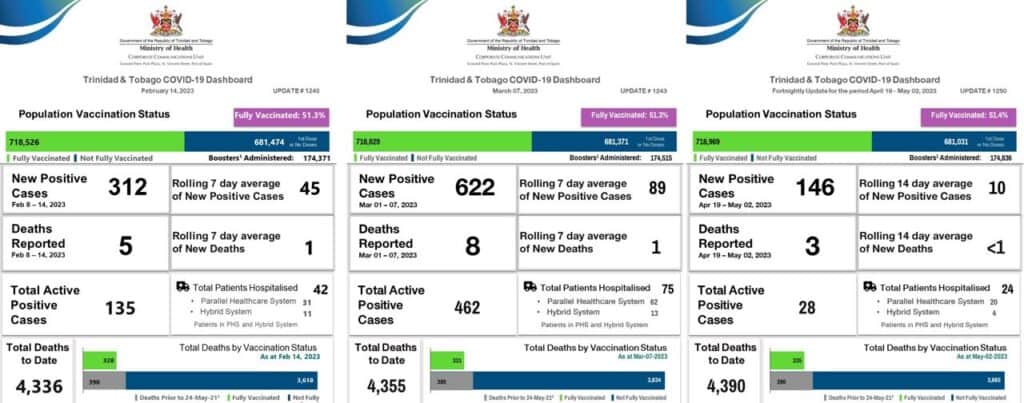

What followed over the festival is a matter of Ministry of Health (MOH) record. On February 14, there were 135 cases tracked by the MOH. Of those, 42 required hospitalisation.

The February 21 report dropped the number to 35 active cases. A week later, the active case count was 396, then a week after that, 496 cases, a fortnightly increase of 1,317 per cent.

Two weeks after that, the active case count dropped to 210.

On May 04, the director general of the WHO announced that covid19 was no longer being managed as a public health emergency and was now considered an ongoing health issue.

The May 02 MOH report lists 28 active cases, with 24 requiring hospitalisation. It would be the last report. The MOH has since stopped covid19 reporting.

Barring any terrible mutation, covid19 seems destined to become another endemic annoyance, flaring up from time to time and requiring public health reminders.

The virus clearly hasn’t gone away, but it isn’t the mortal threat it was in March 2020.

Between April 17 and May 14, 2.6 million new cases and 17,000 deaths were reported with concentrations in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific.

So I hold a mask in my back pocket, alert to situations in which there seem to be too many people, too close together, shouting entirely too loudly.

Three years of concern over potentially lethal invisible life forms should have left us a bit wiser about the value of commonsense hygiene, but those prophylactic measures are disappearing all around us; relics of fear when the world hid from unseen terrors.

What should we have learned from almost three years of bunkered terror?

I have developed a personal appreciation for masks as a barrier for micro-particles, of which viruses are only one.

If nobody else will say it, I will. Medical doctors, particularly calm, reasoned and sensible ones, are a resource we take for granted until they are called on to reassure an entire nation. TT is quite lucky to have so many.

But, the country is at risk of losing much of what was learned by force during the pandemic.

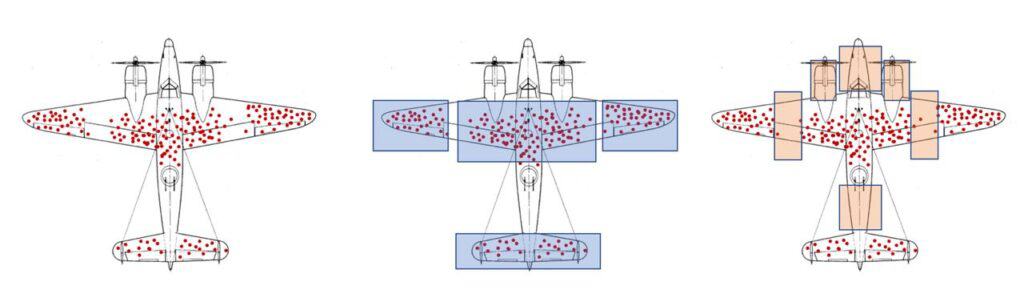

During World War II, returning bombers were analysed for weaknesses. The concentrations of bullet and flak holes in their fuselage suggested that those were the spots that needed better armour.

But, statistician Abraham Wald pointed out that the returning bombers were an illustration of everywhere the aircraft could be hit and still fly.

It was everywhere else that needed to be armoured, because planes hit in those areas did not return.

It’s called Survivor Bias today, and it warns of the danger of examining what worked to find solutions instead of understanding what went wrong and led to failures.

Why did 2,800 children drop out of primary and secondary school during the pandemic?

Why were so many of the country’s 4,390 fatalities attributed to co-morbidities and which specific non-communicable diseases made these patients so vulnerable?

The profiles and possible inequities that fuelled those numbers is worth investigating.

It’s human nature to salute everything that went well, but those are the bullet holes of covid19. We need to catalogue and dissect the errors that led to these terrible numbers.

Greater resilience has to be built into the country’s systems, from governance, and education to commerce. The pandemic tested TT’s approach to all three and found each to be wanting.

The lasting lesson of the pandemic is that as a nation we need to be prepared to move faster and more decisively to identify problems, craft solutions, and implement them. “Let’s find out,” should become a codicil to the national motto.

The leisurely pace of government planning and infrastructure collapsed globally in the face of the speed and ruthlessness of covid19.

Action had to be taken during uncertainty and some of it was misplaced and in error, but it was by moving quickly that the world began to understand what worked and what didn’t.

Those are the lessons that need to stick. Meanwhile, keep a mask handy.