Above: Nuphy’s 75 percent keyboard.

BitDepth#1400 for April 03, 2023

A return to mechanical keyboards was an incidental decision after I put my laptop on a riser.

With the computer’s keyboard five inches above the desk, an external keyboard became a necessity.

The laptop is where most of my typing gets done, to the tune of around 5,000 words a week, but being a keyboard diva wasn’t part of my experience.

Over the years, I’d just adapt to whatever was in front of me. Some keyboards were great, others were annoying.

The worst was my last laptop, a 2019 MacBook Pro that looked great, but I’d end up with random spaces in the text,

The little homing bumps on the ‘g’ and ‘h’ keys weren’t prominent enough, and I’d sometimes miss my finger placement, typing strings of gibberish until I glanced at the screen.

Deciding on a keyboard ended up being a deep dive down the rabbit hole of modern mechanical keyboard design.

Let’s back up a bit here to note that I learned to type on an old school cinder block of a typewriter that punched holes right through the paper in characters with closed counters, like the letter g.

I eventually learned proper touch typing on an IBM Selectric, which demanded far less effort to effectively press the keys. That experience is recounted here.

Jumping to the world of computers, the migration from Selectric-style raised keys to today’s sleek chiclet style keypads was a process that took almost 20 years and during that time, I hardly noticed how I’d adapted to using successive keyboards.

A recent desk redesign forced me to think about what I would use to replace the computer’s default input.

And that turned out to be no easy decision.

Nostalgia for early battles with the keyboard encouraged a return to the tactile feedback and yes, satisfying noise of a mechanical keyboard.

Despite the ubiquity of low-profile chiclet keys, the mechanical keyboard is enjoying a dramatic resurgence, reflected in both the variety and sometimes astronomical cost of the best models.

In choosing among this abundance, be aware that there are four main designs.

The full-size keyboard replicates the massive keyboards of the earliest computers, with a full complement of well spaced letter keys, a top row of function keys and arrow, page up and page down keys to the right of the main key array, agreeably spaced between a full number keypad.

It’s the most comfortable keyboard layout, but it’s big. Putting two of these next to each other requires a spacious layout.

If all those keys are important for your work, a 96 per cent keyboard layout can be an effective compromise. All the keys are there, but compressed into a tighter space that may demand some reorientation.

Other popular versions shrink in size to 80, 75 and 60 per cent of a full-sized keyboard, with a commensurate reduction in either key area and/or a disappearance of key groups.

Bigger size reductions are found on TenKeyLess (TKL) keyboards that entirely eliminate the number pad.

On a 60 per cent keyboard, the key layout and spacing match the layout on a standard 13-14 inch laptop. But these keyboards drop the arrow keys, diminishing the usability of a keyboard too much for serious typing.

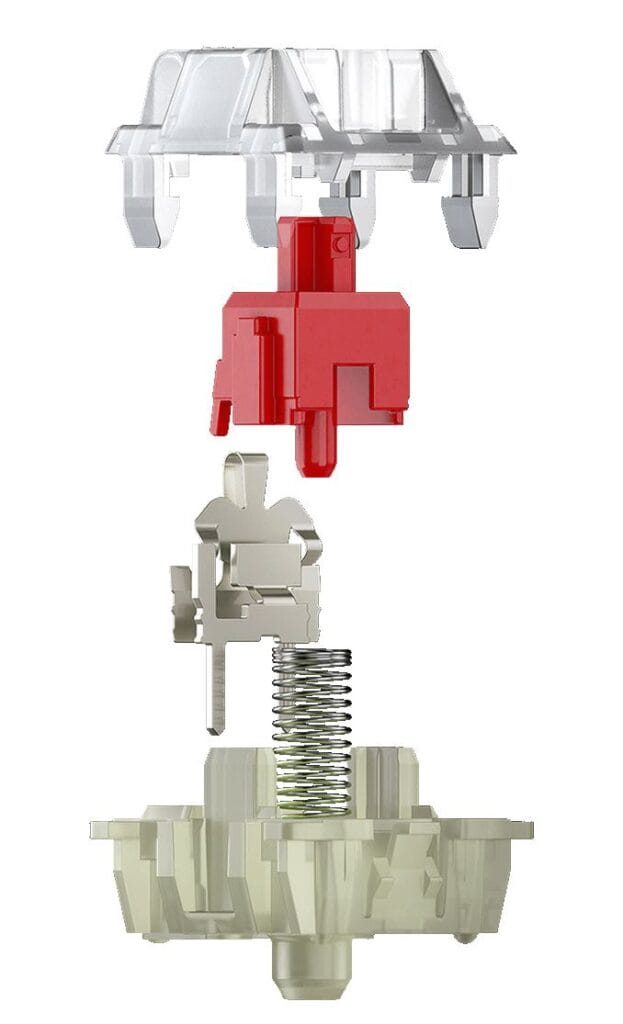

Beyond the size of the keyboard are the mechanics of the key press. You’ll see the name of the German keyboard manufacturer Cherry show up often, specifically referencing its MX line of switches, available in red, blue and brown versions, each with its own characteristics of travel, noise and resistance.

If you happen to work in close quarters with colleagues you may want to consider models with red switches and gaskets that reduce typing noise, but who really wants to limit the triumphal chatter of inspiration?

The patent on Cherry’s switch design expired in 2014, so there are clones and variants available from several manufacturers, including Gateron, Logitech and Razer.

On many commercial keyboards, it’s possible to pull the switches as well as the key caps, most of which are designed to be Cherry compatible.

Hardcore nerds can find DIY kits online that allow the industrious to match a case, switches and keycaps to taste.

The Keychron K2 keyboard that I’ve been using for the last 18 months uses Gateron Red switches but is available with brown and blue switch options. It shipped with Mac specific keys in place with a key puller and four conversion Windows keys. There’s a toggle switch to adjust key mapping from Mac to Windows.

Easy key caps removal has also created a side economy in alternative keycaps for the style conscious.

The resurgence of mechanical keyboards began with gamers, possibly because the tactile response is close to the physicality of gaming controllers.

As a result, there are lots of alarmingly colourful, angry looking mechanical keyboards on the market.

Those are a bit distracting for bashing out long bits of text, and more sedate, office-appropriate choices fall between affordable lines from Keychron, Coolermaster and Logitech and pricier, up-market items from brands like Das and SteelSeries.

Key features in a mechanical keyboard.

Be sure to get one that connects using both USB and Bluetooth. Wireless seemed a good idea, but I eventually switched to wired.

If you’re considering a larger keyboard, go for one with QMK and VIA compatibility, which will allow you to reassign keys using open source software.

The difference in size between 60 and 75 percent keyboards isn’t that great and the extra keys are useful in day to day typing.

Get backlighting. Plain white will do. Matias has an excellent Bluetooth keyboard for Mac users with Alps clone switches, but alas, no backlight.

Keyboards don’t live in the prominent and stylish spaces they occupy in product photos. A backlit keyboard is invaluable in locating home keys when you return your fingers to the keyboard.