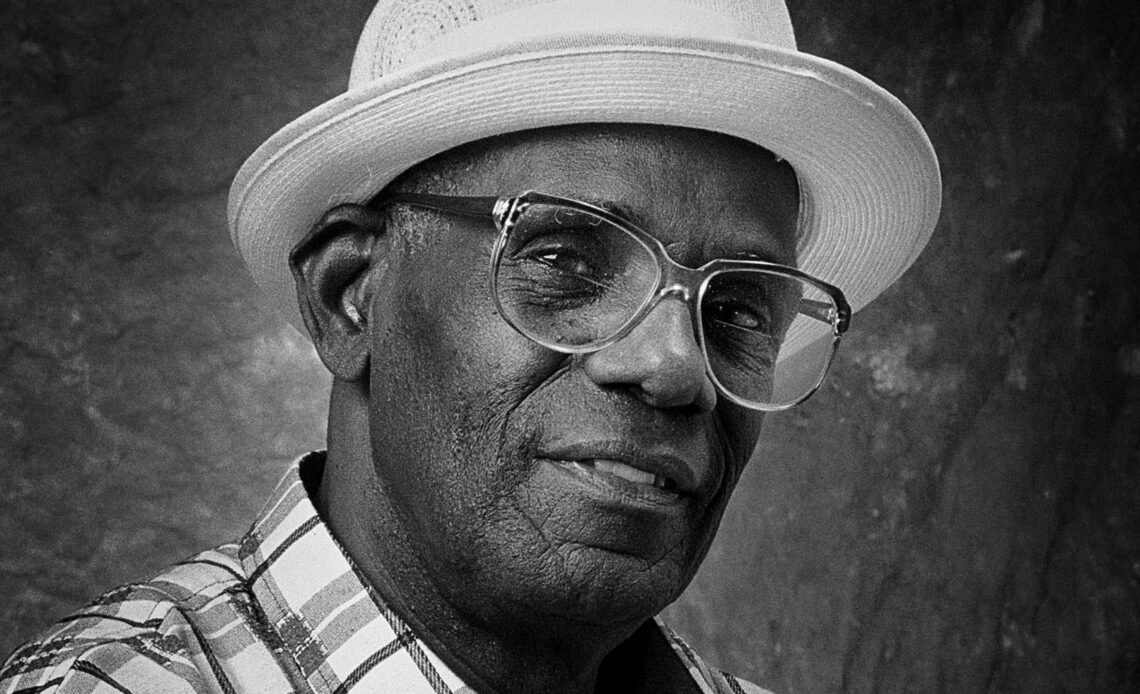

Above: Clifton Ryan, The Mighty Bomber, photographed by Mark Lyndersay in 1994 for a project by David Rudder, who was preparing a group of vintage calypsonians for an international tour.

BitDepth#1337 for January 17, 2022

Last, week, a major local media house stole one of my archival photos of the calypsonian Bomber and used it in advertising for a broadcast.

This followed an incident last year when a leading advertising agency pilfered two images from my Calypsonians 2020 project for an outdoor promotion.

I don’t usually shirk from callouts, but I’m giving both companies a bligh because when confronted with the infringements, they agreed to my fee without complaint.

In conversation, we often try to diminish this kind of abuse of intellectual property (IP) with gentler words.

The words ‘inadvertent,’ ‘mistaken,’ and ‘careless’ are offered as explanations for making commercial use of something that doesn’t belong to you, which you didn’t create and that you claim not to know the provenance of.

Any of those three conditions should be a red flag to stop, look and Google again, particularly when it comes to, say, an image that you found on the internet to begin with.

“I got it on Google,” isn’t an excuse. Google isn’t a resource for images.

It links, often deeply, to other internet resources and when they go away, the search ends in 404 errors, indicating that a file is not found.

It actually doesn’t take much effort to find out where a digital file originates, but a surprising number of people looking for IP don’t bother to make the effort.

Trinidad and Tobago has a national inclination to piracy of creative works for commercial gain that was best demonstrated by the once-popular ten-dollar DVD duplicate of a multi-million dollar film.

Attentive readers will be aware that I make a living as a photographer and have done so for decades.

During that time, the imbalance of local copyright has swung slowly but steadily back in favour of the creators of IP.

Not that long ago, insisting on your copyright was a sure way to lose work opportunities in the commercial photographic space.

The occasional rights grab still surfaces as a condition of working, but there are compelling reasons for creators of IP to hold on to their rights.

The most important of which is the potential for images to retain or even gain value, because I have no reason to hold on to any image I don’t own the rights to.

But with that position comes responsibility.

I’ve held on to most of the negatives and transparencies I shot in the first two decades of my career and now face increasing an challenge in turning them into digital files as the era of affordable film scanners shudders to a close.

It takes diligence to preserve film, effort to digitize it and patience to clean up the imperfections that a good digital file reveals.

Over the past three years, I’ve made just a bit more money from IP infringement claims than I have from formally licensing images, because when people get caught out today, they tend to accept what’s been done as wrong.

That wasn’t always the case.

Some of the change is the result of greater awareness of law and the value of IP, but there is also the importance of a case brought by Sean Drakes against Donald Grant in 2018.

The judgement by Justice Ricky Rahim in January 2021 (CV2018-01224) established case law for the rights of photographers when their work is used without permission or recompense.

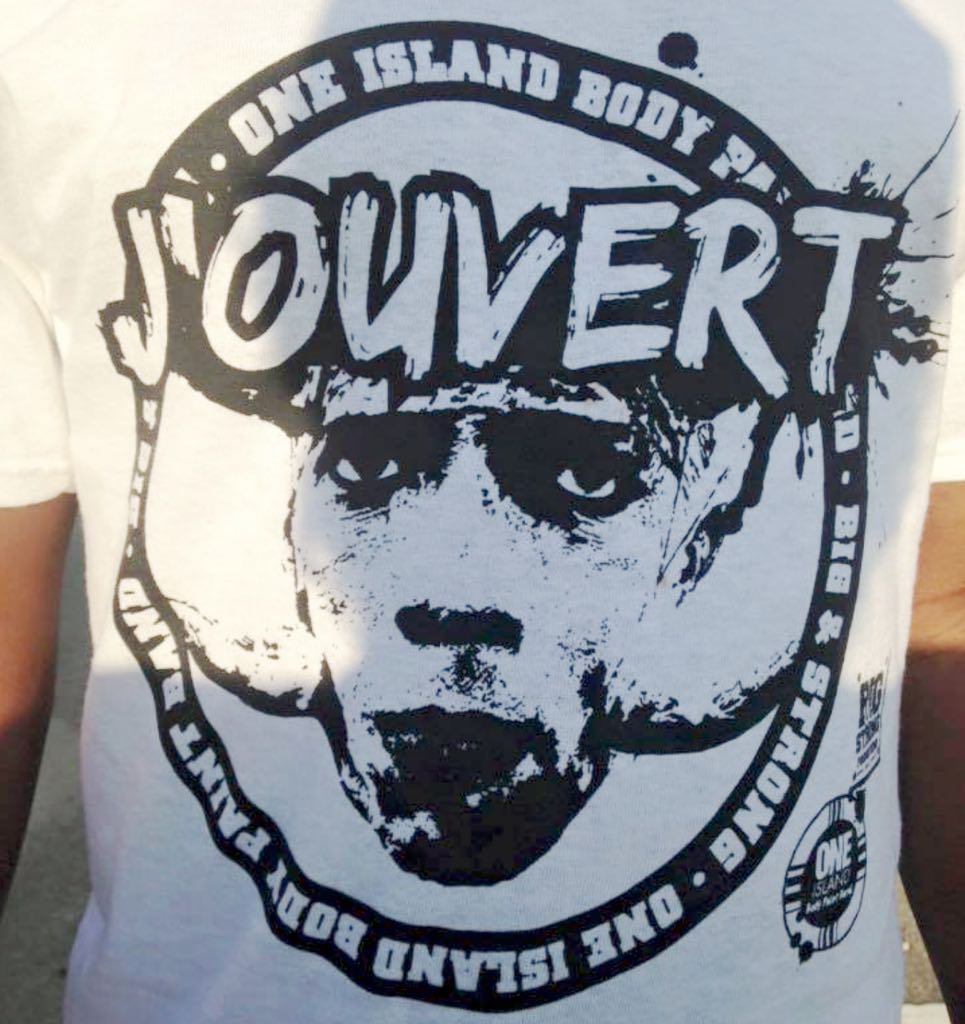

Maria Nunes found out about this particular image theft in October 2015 from a friend who was in the middle of Miami Carnival and was certain the image on the band’s t-shirts was one of hers.

She found the image on the website of the One Island Body Paint Band, where the band shirts were being sold for US$100 each. She emailed the band. They did not reply. Then tried calling without success.

“Eventually,” she said, “I just let it go as it’s very exhausting to seek redress in this kind of copyright breach.”

Maria Nunes, known for her extensive work with traditional Carnival masqueraders, described challenges with her photographs of Senor Gomez when he passed in 2016 and after her photo of Narrie Approo was published in a local paper without her permission last week.

She did not consider a byline in the paper stating “courtesy Maria Nunes” to be adequate.

“This was untrue,” Nunes wrote in a WhatsApp message.

“No-one had the courtesy to contact me to ask permission.”

Even when permission is granted, Nunes has found that the inch given is often extended by miles, with photos going on to appear on Instagram with no credit and the media house’s logo watermarked on it.

When proper credit is omitted, the assumption of authorship drifts to the media house and when that happens, it inexorably drifts away from the creator, creating needless confusion in the public mind.

“It’s important (that) we build a better understanding of our visual archives and what it takes not just to create the work,” wrote Abigail Hadeed in a message as she considered what’s necessary to preserve intellectual property rights.

“But it then becomes incumbent on us to also maintain, upkeep and manage.”

Hadeed curated a landmark exhibit of historical photographs at the Art Society, Record : Art : Memory in 2012.

In a note in the catalogue of that exhibition, Hadeed observed that it was easier to find images of colonial Trinidad than it was to find images of the country post-Independence.

“I became painfully aware that a great deal of our photographers’ images and newspaper archives have been lost,” she wrote.

“I was deeply saddened to learn that many individuals did not deem their work important, to such an extent that decades of work had been discarded and thrown away.”

In so many of these cases, the intellectual property that is being stolen is both rare and the result of self-funded investigation into aspects of culture which attract little mainstream media attention.

The result is that the casual misuse of creative work becomes a punishment to its creators who then bear the burden of seeking out fair recompense.

This does not act as incentive to the creation of such work or the intensive and expensive efforts that preserving and archiving it demands, further guttering the public record of our disappearing culture.