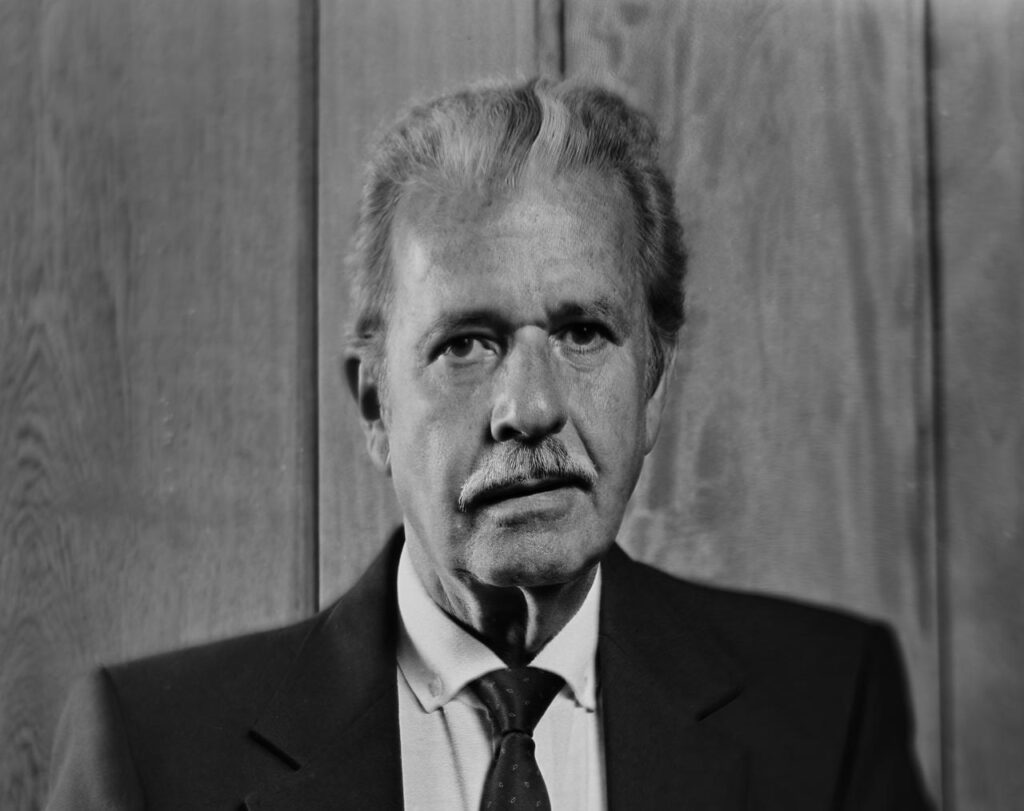

Above: Alwin Chow, the Trinidad Publishing Company’s Managing Director – Designate, photographed in 1989. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1333 for December 20, 2021

1998. Alwin Chow had just taken up the role of General Manager at the Express and he was busy making the space his own.

I’d been doing projects at the paper for most of the five years since leaving the Guardian and with Lenny Grant gone from the paper, I was at a bit of a loose end.

So I visited his new office to find out how I could help in his new role.

“What do you want to do?” he asked.

I made a stupid quip about being underemployed and we promised to meet again. Grant called soon afterward and asked me to join him at the Guardian. I never saw Alwin Chow again after that.

1986. “Jo Jo, this is Mark,” Judy Chow said as we walked past the living room of the family residence in Haleland Park.

Mrs Chow, Alwin Chow’s first wife, was walking me to her cozy darkroom, the centre of her dream of becoming a photographer.

Chow got up from relaxing on his couch and in t-shirt and shorts, gave a little wave before ambling off.

That was the first time I met him. While I never quite understood why he asked me to do training at the Guardian in 1989, he did and I accepted.

I think he had an intuition about people and was willing to try them in bigger roles to see what they might become.

I’m sure I lent Judy Chow copies of the now-defunct Photo District News, a trade publication for professional photographers that was brimming with reports about digital photography.

To hire me for the training, he had to go against the sitting Managing Director, Mark Conyers, who had banned me from the paper’s premises after I sent him an invoice for two sheets of 35mm colour transparencies that the paper had lost.

Mark Conyers and John Pocock, the MD and GM if memory serves, were old-school McAl people, the masters of management who were positioned diametrically opposite the generals of journalism positioned at diagonally opposed ends of the second floor of the Guardian building.

Lenn Chong Sing, Carl Jacobs and Therese Mills sat in equivalent offices, made from the same expensive European prefab partitioning at the north-east of the office floor.

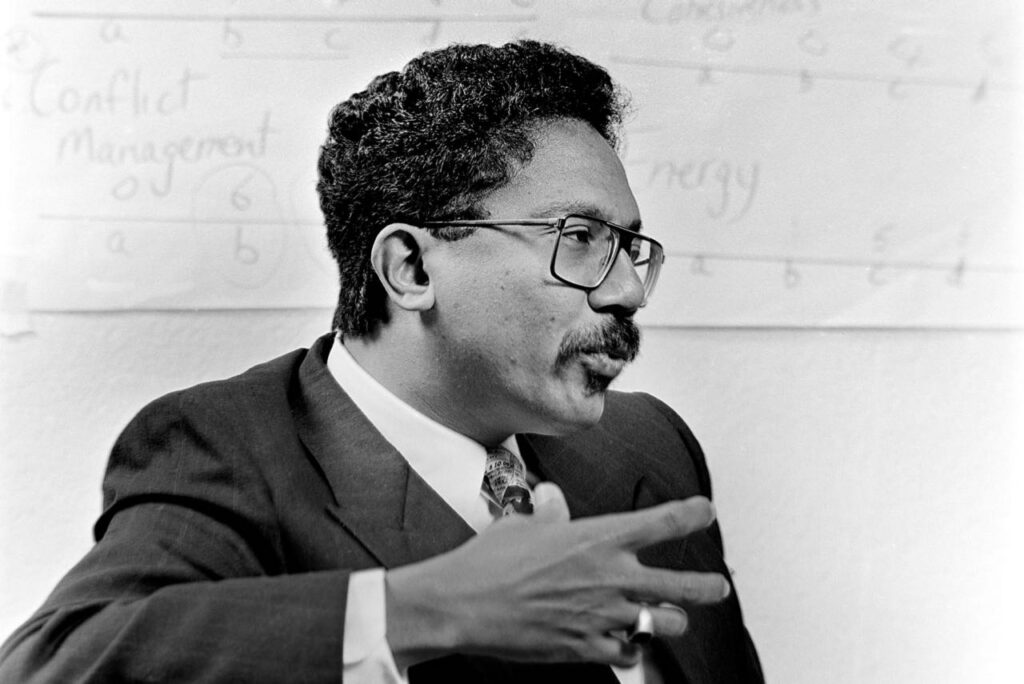

Alwin Chow ignored all this careful structuring and curtaining of the journalism enterprise. He was an ANSA man and he came to haul the Guardian into the 20th century despite every indication it would do so kicking and screaming.

The training and parallel evaluation of the Guardian’s photographic department went well, and I produced a comprehensive report for Chow, who then asked me who I thought could execute it.

I was hoist upon my own carefully worded petard.

Having served as a freelance contributor for the paper for years and winning the confidence of Mrs Mills to produce printable colour images for her Sunday paper, I had big ideas for the role of photography in the paper generally, particularly when it was considered perfectly acceptable to print a three column grip-and-grin PR photo above the fold on the front page of a daily edition.

So I joined the paper’s staff in January 1990 for the first time, fired by the confidence that Chow had invested in me and inspired by his bold, if still fuzzily defined vision for the paper’s future.

By then, the combustible relationship between Chow and Lenn Chong Sing had led to the latter’s abrupt retirement.

The newly appointed EIC, Therese Mills, was working to solidify the footing of the editorial department in an environment that was characterised by a cheerfully intrusive new MD.

The Guardian at the time was in a powerful position as the leading newspaper in the country. The Sunday paper’s run began on Saturday evening to get 150,000 copies off the press before daybreak the next morning.

The paper would probably have continued using the badly aging Microtek word processors that ran the newsroom for the rest of the decade despite their constant glitching, but Chow wasn’t having any of it.

Chow approached project management at the Guardian the way a WASA backhoe tackles virgin asphalt, with remorseless vigor and moderate accuracy.

He intuitively understood that there were four elements at play in his plan for evolving the paper; time, money, people and technology.

He didn’t want to waste time, so he persuaded ANSA to invest lots of money in the remaining two.

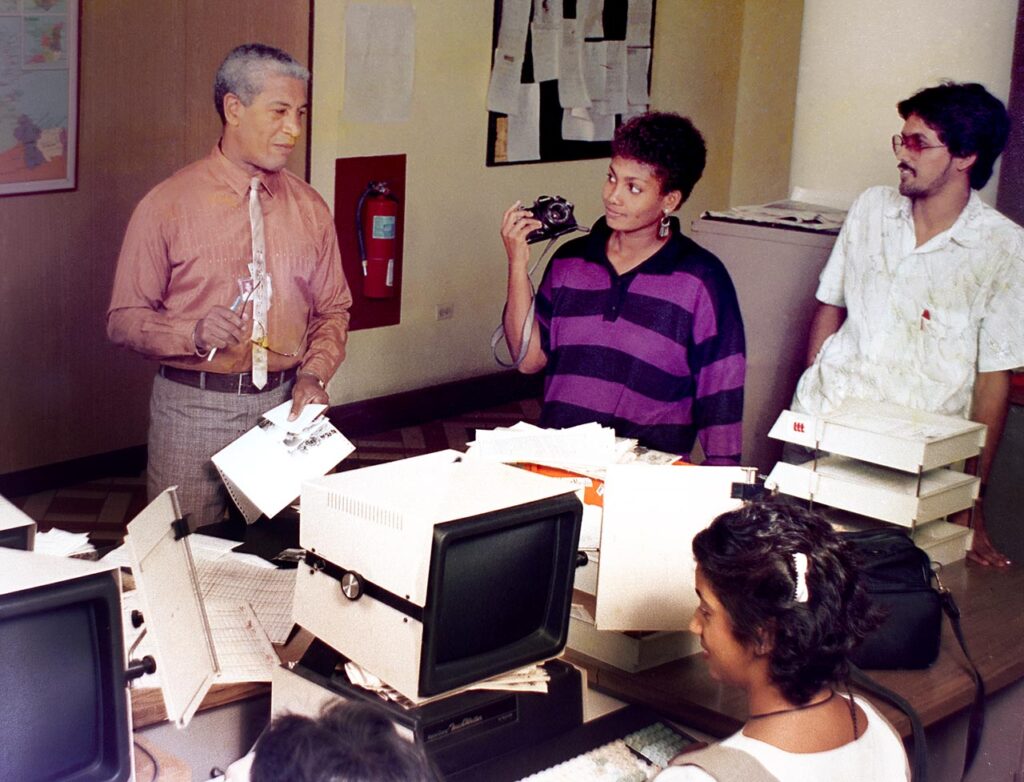

He brought in a raft of ‘management trainees,’ degreed young graduates with zero journalism experience across the paper’s business structure.

Some were slotted into the newsroom, an entire IT department to support the newly purchased Macs was constituted out of their ranks, and technology was unboxed at the paper at a frantic rate.

So much of it failed at first. The first networking effort using Apple’s LocalTalk system used phone wires, but couldn’t support the size of the files moving over it, so a ‘sneakernet’ moved bigger files around on floppy disks and later, Syquest drives.

The first raster image processors (RIPs) couldn’t handle a full page of text and images for output to negatives, so a system of partial pagination, with most of the page output to text layout with images stripped into it afterward was instituted.

In any other era, the effort might have stalled out there, but Chow wanted full pagination. He wanted the paste-up department gone and everything running on wires to the pressroom.

I once casually mentioned to him before he flew out to a technology trade show that he should look out for smaller, more affordable film scanners.

He returned with one in his luggage, acting immediately on my inadvertent tip-off.

The networks were eventually upgraded to ethernet, an expensive Sun workstation was installed as a dedicated RIP and eventually fully paginated pages rolled out as massive negatives spewed from massive, deepfreeze-sized imagers to be burned to printing plates.

There were many occasions when the equipment simply failed. He could accept that, but he wouldn’t accept people just giving up.

When the subeditors refused to use the Macs put in front of them, he threatened to fire or reassign them, but in the end settled for a system of paginators, who would build the paper on the Macs to page plans laid out by the subeditors.

I learned about these technical moves because of Photoshop 1.0.

Chow flew in an Adobe certified subject matter expert to install and introduce the software and told me I was his host for the visit.

When I saw his demonstration of Photoshop, specifically the use of a clone tool to remove a scratch that reduced a half-hour’s worth of work with a spotting brush to four seconds and six clicks of a mouse, I knew that whatever was happening with these computers was something I needed to understand.

And Chow indulged me.

By then, I’d befriended some of the young paginators, particularly Dexter Lewis, who along with a couple of others, had been copyboys who had turned their chairs at the subeditor’s desk around to face the computers behind them during their downtime.

Lewis had been showing me how the computers worked and then adventurously produced mockups of what the Sunday magazine could look like in full pagination.

The magazine was a particularly tawdry, formulaic thing then, stuffed haphazardly into the paper, but I’d contributed splashy color covers to it in previous years, providing lipstick for a particularly unreadable pig.

Those laser prints sold Chow on the project as a pilot for what could be done with the paper and with the blessing of Mrs Mills, we pressed ahead. The first version was rolling off the press at six in the afternoon on July 27, 1990.

That press run ended abruptly in gunfire and our appalling desktop publishing errors mercifully disappeared.

When we got a chance to do it again (Chow was really keen on full pagination), I commissioned a logo from designer Gabby Woodham, and again got into trouble because Woodham had to be paid a sum the Guardian never spent on design services.

Chow stepped in again, taking the bill from me and dealing with it.

That’s when I realised that once you were on his team, he’d take a bullet for you.

He stepped in again when the entire photographic department decamped to Independence Square to complain about my performance as Picture Editor (I was really spending way too much time around those computers), bluntly telling ANSA’s managers that the accusations were bullshit.

I’m conjecturing about the actual words he used, but it wouldn’t have been out of line for him.

He was fierce and unflinching about pet projects and when he became determined to produce an 80-page Carnival supplement that he planned to sell from shopping carts on Ash Wednesday morning at Piarco, nothing was allowed to derail the project.

Of course, things went all kinds of wrong and around six in the evening on Carnival Tuesday, he appeared in the sub-editor’s bay, where pages were being assembled, images scanned and proofs reviewed, more than a little tipsy. Nobody thought we were going to make the deadline.

He’d just come in off the street, red-faced and stern, to declare, “I am hearing that this magazine will not be produced on time.”

We all looked at each other in absolute silence, not a finger daring to press a key.

“I want you to know,” he declared, his voice steadily rising, “I am not accepting excuses tomorrow morning, I am accepting resignations!”

The magazine got finished on time, if somewhat haphazardly at the end.

I remember editing six-inch stacks of postcard Carnival prints like a card shark, flipping selects into a tiny pile to be gang scanned to fill pages.

Looking back over the three decades since then, the pace of technology adoption at the nation’s newspapers has been a slow, painfully constricted process.

What Chow did in the two years I worked with him at the Guardian would be stretched out over a decade elsewhere, as time proved the favored currency over bigger investments in cash, people and technology.

I write often about the intersection of technology and journalism, often with more than a little frustration at the pace of that merging of interests locally.

In the last decade, the need to spend on people and technology in journalism has clearly taken precedence over cash and time.

The efficiencies of internet distribution of information and the pace of its development mean that it’s possible to do more, faster, with a dramatic reduction in cash outlay, but understanding and implementing technology correctly and delivering powerful journalism demands talented, knowledgeable people more than ever.

In the end, Alwin Chow was proven right in his efforts to revamp the Guardian. He pushed for better people and better technology in 1990 and if he’d remained in the business over the last two decades, I’m certain that TT journalism would look very different today.