Above: Petrotrin flared gas as part of its refinery process for decades. The flame finally went out when the refinery shut down. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1286 for January 28, 2021

The history of Carnival as a cultural festival is deeply entwined in both this country’s experience as a colony its creation as a source of resource extraction.

There are some interesting parallels that emerge if you compare the development of Carnival with the growth of the oil and gas industry in TT.

Carnival began an act of defiance and its very structure was shaped around the kind of giant middle finger that old mas maestro Dick Butts might have created to flip at the colonizer architectures that systematically stripped this country of everything it could produce.

In its design, the event was a self-immolating act, an Icarus-like soaring to the heavens, leaving only ashes behind on the day after Carnival Tuesday.

The costumes were collected and dumped by city disposal trucks.

For long decades, the music we produced was banned, in the name of Lent, from being played the day after it was trumpeted from every street corner.

It was flared gas as culture, burned away in a consuming act of ignorance and misunderstanding of the value of everything that we created with love and enthusiasm for long months.

But even in the oil industry, flared gas wasn’t completely wasted, despite those burning jets of hot flame arcing into the sky on oil platforms.

Some of the gas was routed through private pipelines as cooking gas for the camps of workers servicing the industry, little villages that would become towns.

In Carnival, there were equivalent acts of value salvage. Some forward looking calypsonians recorded 45’s of their most popular songs, travelling to the US to record with Decca and RCA Bluebird.

Photographers and cinematographers captured bits of the spectacle. Stumbling efforts were made to record the steelband, much of the work almost incomprehensibly bad.

Carnival is no more a product than the extractive industries are a product. They are both systems which are supported by the creation of products, but they way they were handled was vastly different.

Making a product in the petroleum sector was the entire point of the industry.

Carnival’s managers, however, did everything possible to do exactly the opposite. If there were ever a word like “deproductize,” it would apply to the management of the festival.

An entire era of big band music supporting Carnival, an annual creation of intricate arrangements and passionate performance, was systematically destroyed by that soulless competition, Brassorama.

When DJs took over the festival’s music programming, live music had been so gutted of inventiveness and musicality that it could offer no competition to massive speaker boxes strapped to trucks, playing the same song with repeat precision.

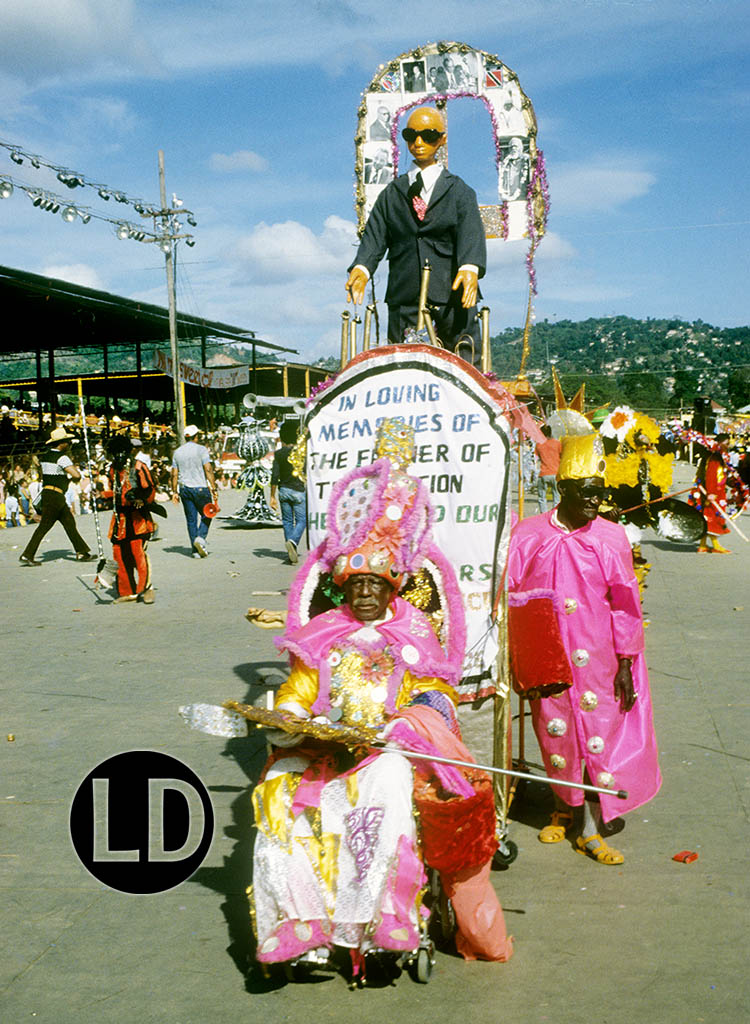

At roughly the same time, the epic awesomeness that was old mas, a celebration of bawdy, over-the-top, classically Trinidadian humour, died quietly.

Killed by political disinterest in its untidy characterisations, the event didn’t even get a suitably theatrical death scene.

The executive effort to make Carnival an ephemeral event ensured that every effort to package, produce or preserve it has been met by stout resistance and contempt.

In 2008, I spent a year documenting the work of Tribe who brought system design to the production of carnival costumes.

Before that, I’d been witness to the evolution of Machel Montano from tween curiosity to road march powerhouse.

Some may choose to dismiss Dean Ackin and Machel Montano, but I’ve long seen their insistence on systems thinking and commitment to creating engines of production as crucial to an overdue evolution of the festival.

There are others; though few are as polarising a lighting rod for opinion as Ackin and Montano, but most of their detractors manage to get everything about them wrong

They aren’t destroying the culture, they are, within the strict and largely pointless limitations imposed on the festival, creating something sustainable and lasting in an event designed to collapse and disappear.

The Culture Ministry should take a long, serious look at the history of the Energy Ministry and how it managed a finite natural resource.

The NCC should examine the work of the NGC, to see how a state agency routed a resource from burning into the air into a value proposition that sustained TT for decades.

Every major energy company operating in this country has extensive records of every project.

I know this, because one medium-sized company hired a good friend of mine to scan crumbling seismic scans and geographic information to create digital files for its engineers and scientists.

By contrast, the only record we have of Terry Evelyn’s legendary costume, Beauty in Perpetuity, created for George Bailey’s Bats and Clowns, is a photograph by Noel Norton. Does anyone remember Charles Peace? Edgar Whiley? Puggy Joseph?

So many spontaneous acts of transcendent art and expression have disappeared over a century and a half of institutional carelessness.

Until 2020, the annual Carnival celebration remained a system of flared gas, burning its best and brightest off in the name of a tradition of competition, ignoring the value of collaboration.

The incandescent beauty of that mass immolation distracts from the monumental destructiveness that has characterised the festival. Just because something is pretty doesn’t mean that it isn’t toxic and wasteful.

Perhaps the best thing to happen to Carnival as an event was its covid19 mandated cancellation.

Without the trappings and boundaries that have evolved to contain it in a hamster wheel of activity, its creative contributors now have a chance to think about what they have really been doing and to pose the questions that the distraction of constant partying kept postponing.

The musicians and composers have come to the table first, streaming work that recontextualises and reconsiders vast catalogues of calypso and steelband arrangements.

The potential is vast. If a creative product can be effectively packaged and streamed into a West Indian living room, it can also be delivered and enjoyed anywhere in the world.

By closing our little stages for 2021, we now have an opportunity to consider how to make our creative work ready for a vast, diverse global stage.

There will be mistakes, there will be wrong turns and there will be failures, but if we reconsider Carnival as both cultural nexus and creative product engine with the same inventiveness we invest in producing it, the returns are potentially incalculable