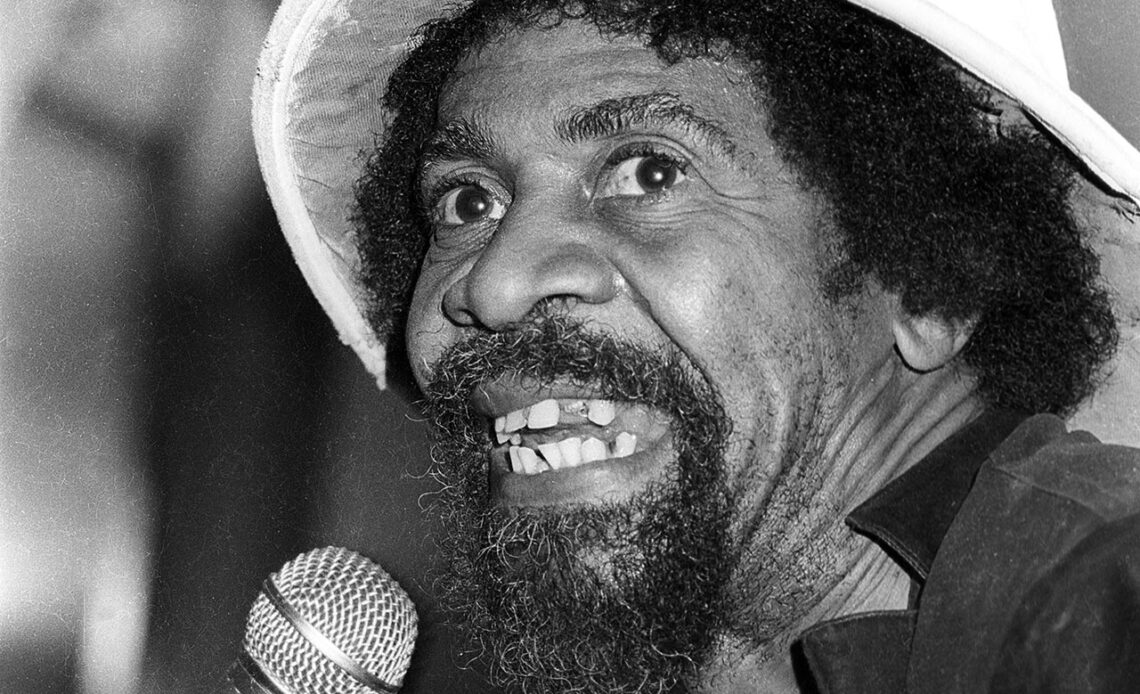

Above: Bill Trotman performing Monkey See, Monkey Do with the Original Young Brigade tent at the SWWTU Hall in 1982. Photograph by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1284 for January 14, 2021

At the end of 2020, National Carnival Commission chairman Winston “Gypsy” Peters ended any speculation that the commissioning body of Carnival might try to present a contemporary event online.

Declaring that TT cannot have a virtual Carnival, he promised, “an antecedental look at what Carnival in TT is all about, historical as it is.”

“What we are going to be doing is compiling a lot of what we have,” Peters promised.

“We are working on it right now.”

This was the result of three months of deliberation after the NCC promised stakeholder consultations on “restructuring, innovating and digitally promoting Carnival” in September.

I could not laugh. I could not cry. But I feel an overwhelming sadness about the continuing destruction of the creative capital of this country, delivered in the guise of professional governance of this festival.

I’ve put bloody skin into the Carnival game since 1979, but in 2014, I turned my back on the Queen’s Park Savannah after more than 30 years of photographing the festival at that venue.

For decades, I’d been part of a cadre of journalists and photographers who showed up to work in conditions delineated and defined by contempt.

The NCC has built the structures, dispensed the funds, kowtowed to the politicians, handed out thousands of largely meaningless trophies and thrown a cloak of culture over a shambles of mismanagement.

Until the Savannah approach was paved – controversially by Carlos John in 1999 and to the detriment of the capital city’s watertable – the wind would whip dust, ground fine by stamping feet, across the stage directly into the face anyone standing in the photographer’s pit at the south-west end of the stage.

Most years, I’d lose my voice by Carnival Tuesday, but I chose to keep the media passes that proudly insisted that the bearer had no entitlement to a seat.

The gulf between that sacred stageside purgatory and the air-conditioned suites where champagne flowed at the apex of the Grandstand defined the gap between the intent of the NCC and its appalling execution.

The visual documentation of Carnival was formally managed as a nuisance to be tolerated. Better to enjoy the event with Moet from behind a glass window at a suitable distance from its messy reality.

I do not know Winston Peters, but I’m sure he means well.

That doesn’t excuse or remedy the many years of institutional misadventure that have characterised the NCC’s role as a tool of political control or its tone-deaf management of the festival.

I should point out here that two of my cousins have had leading roles in the management of the NCC. When I realised that neither Alfred Aguiton nor Colin Lucas could make sense of the aimless meandering of the commission, it became clear the NCC does not have management problem, it has a flawed mandate.

The NCC and its predecessor, the Carnival Development Committee, have never been about evolving the festival. There has never been any serious attempt to either understand or guide its growth.

The people of this country want Carnival, and therefore the NCC has delivered it in abundance. Until Covid-19

Now there is no event to stage, and I need not ask about the archives that Peters referenced.

There are none to speak of, because a political organisation only needs archive material for propaganda. In 2021, there is nothing to spin.

The crippling confusion that the NCC faces is unsurprising. It has never understood the festival that it convenes.

It has built the structures, dispensed the funds, kowtowed to the politicians, handed out thousands of largely meaningless trophies and thrown a cloak of culture over a shambles of mismanagement, but it has only ever been an engine of continuance, not a source of invention.

Now that there is a need to reimagine Carnival, it must confront its own complete lack of institutional imagination.

A plan to fall back on a nonexistent visual history is doomed to failure.

No money has been spent to create and preserve a media archive of the festival. That has largely been an endeavour of private enterprise and it has been savagely taxed through dubious “copyright” fees.

TTT is the only state institution to produce a record of the festival, and it regularly wiped its archival tapes for reuse.

Private sector media institutions are little different, maintaining archives of published work while allowing the larger documentary record to be eroded by time and disinterest.

The single most important and comprehensive record of Carnival is vested in the Norton Collection, the work of the late photographer Noel Norton and his wife and chief archivist Mary, produced for a half-century in the face of CDC/NCC scorn.

I am being gentle when I describe the NCC’s attitude toward documentation as scornful.

The disdain and disinterest of the NCC’s executive to documentation filters down to the operational level as simple thuggery.

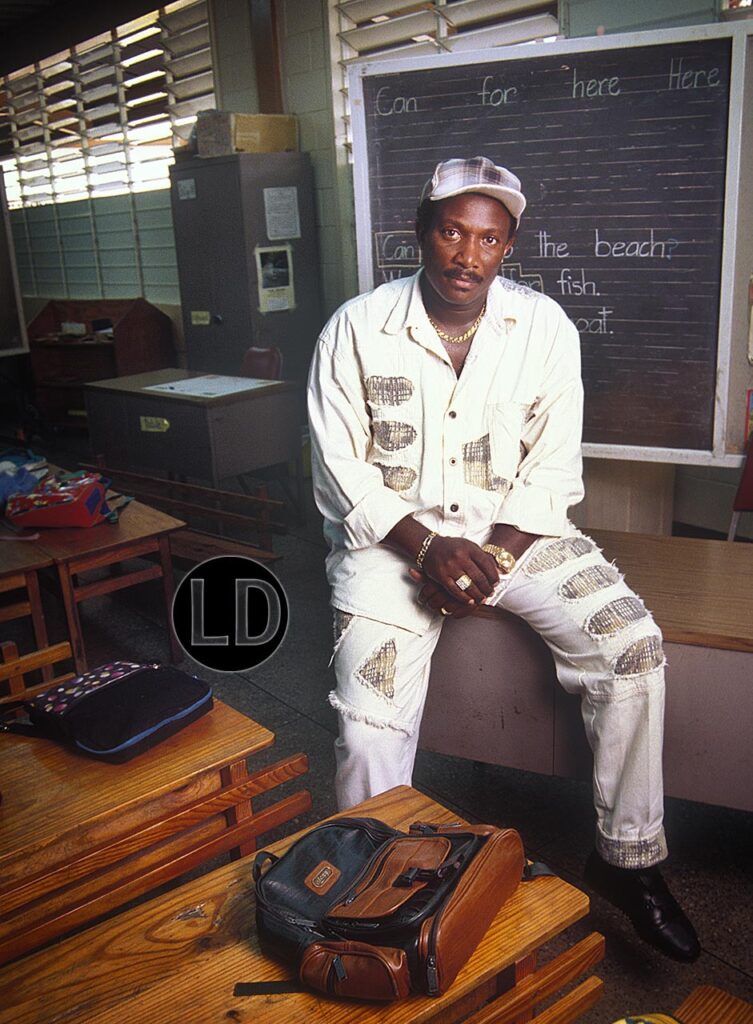

From the police officers on horseback who once dressaged between masqueraders and the public, the journalists dodging between them, to a tragic assault by security personnel on filmmaker Horace Ové when he dared to make photographs of traditional mas, the NCC has overseen a destructive misunderstanding of the role of the visual arts in Carnival.

Hosea 8:7 warns that those who sow the wind will reap the whirlwind.

The NCC demonstrates it’s obverse. Having invested nothing in its own history, it is now left with only the barren fields of its shortsightedness.

I wrote elsewhere:

The NCC is redundant in the 21st century. When the PM said “Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago in 2021 is not on,” that was a signal for all under the influence of a government subvention or salary to fall in line with that outdated way of thinking: “my way or the highway.” Never a consideration of what was possible.