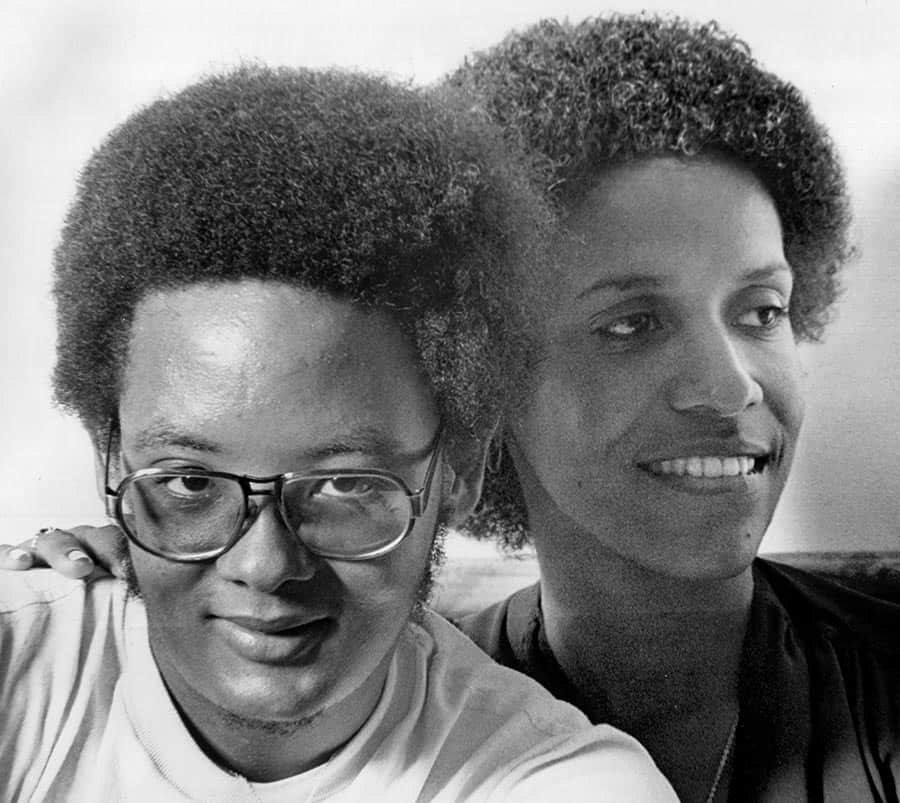

Above: John Belgrave and his wife, Thecla Pierre, 1984. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

BitDepth#1220 for 24 October, 2019

You died last week. Dr. John D Belgrave. Gone.

There are some deaths that leave you curious and confused. When I heard of yours, I just said, “Oh.”

I don’t think I’ve sucked that breath back in since.

I cannot think of anyone who was more fearless and simultaneously more vulnerable in the face of danger than you were.

Born with a skin condition made your soft flesh easy to cut, hemophilia, which made your blood hard to clot, and some double joints on top of all that, you cut an unusual figure on that first day of first form in Trinity College in Maraval.

Most notable was your arrival in long pants, when the boys were expected to wear shorts until third form.

Your mother, a stern and fierce protector of your health, insisted on it.

In the end, even with my own considerable appetite for absurdity, I couldn’t keep up with you.

It also meant you couldn’t be caned, so your inclination to mischief meant that you wrote a lot for atonement, quickly graduating from “The way of the transgressor” to an ever deeper pile of exercise books transcribing the Bible.

By the time you hit sixth form, it seemed that you’d written most of The New Testament.

So naturally we became friends.

When I had my 12th birthday party at a beach house, my mother grudgingly visited your mother to discuss safety.

You were right alongside me when we performed as The Deranged Dancers at a school talent competition.

You were always comfortable playing the fool, but never in a way that would allow anyone to take you for one.

In the end, even with my own considerable appetite for absurdity, I couldn’t keep up with you.

Whether it was exploring the woods above the school, a region declared absolutely out of bounds, or snorkelling among particularly vicious rocks at Macqueripe, you were always out front, urging the timid and sensible onward.

You were never given the gift of the Belgrave athletic physique. Your brother Carlisle had it. Your sons do. Broad shoulders, cleanly defined muscle tone, handsome craggy looks.

You took what you had and with a keen wit, made it your identity.

Your appetites were vast and wide-ranging. For you, the comparison wasn’t between premium single malts, it was whether The Macallan was really better than a legendary bush rum you’d heard was simmering in a biscuit tin somewhere in the back of beyond.

Others might muse; you would find out.

You were my friend from the day we first spoke in gray and white until the day you died.

We didn’t speak often, but we spoke deeply when we did.

I never heard you speak with regret, but the losses you took on the stock market clearly stung. You rallied with investments in real estate and pressed on.

Your work as an energy consultant based in Calgary took you around the world.

One evening you called, your voice buffeted and overpowered by a squall of screaming, hammering sound. It sounded like someone was building a battleship in the middle of the North Sea.

“I’m in Kazakhstan! I just wanted to check this was still your number! I’ll check you when I’m there!”

The thing was; you always would. Trinidad mattered deeply to you. The friends you’d made at Trinity were a touchstone.

When the college nominated you to its Hall of Fame, your brother told a group of classmates last month that you wept.

The two things that kept bringing you back to Trinidad were your ailing mother and the local energy industry, which couldn’t hear your plans and proposals, informed as they were by current industry realities.

I’d listen to you fulminate colorfully about pointless meetings and pointed ignorance.

By then, you probably got the same mute confusion from them that you got from your mother, though she was deep in the grip of Alzheimer’s and you loved her and expected it from that quarter.

After her passing, TT saw much less of you.

It’s something I’ve often considered, this country’s inability to keep track of its best minds working abroad and to make use of them.

In my Trinity school year alone, a group that recently rather archly dubbed themselves the 69ers, are computer scientists, mathematicians and linguists whose experiences working in the world might have informed generations.

Many of us stuck around to kick ass in different fields, but others stayed where they had studied, some unable to return because local approaches and equipment wouldn’t allow them to work at their peak.

So many of these brilliant young men would visit, like yourself, look around, have a few abortive and frustrating conversations and then go back to their lives abroad, unable to find any point of entry in a country so determined to contemplate its own intellectual navel.

You will never be back now. You’ve gone on ahead without me again, this time to the undiscovered country.

The last time we exchanged words, you’d finally logged into Facebook and you’d read a review I’d written about the Samsung Note and bought one. I felt rather pleased and smug about that for quite a while.

It’s a lot quieter here without you, knowing you aren’t in the world anymore. I’ve lost a breath I’d grown used to having around for more than 50 years. There’s a ragged spot I get when I think too deeply about that adventurous past, a gasp deep in the gut that’s just emptiness now.

I’d honestly have preferred that you’d waited around a bit, but I imagine you’ll make good use of the headstart on the carousing.

The whole Federation Generation (born between 1958-1962) was ignored in this country allowing those fine minds to make a way in the world. A nation’s loss, as we contemplate what exists now and note that one by one that Generation is going to the great beyond never to have satisfactorily influenced the nation’s direction. What the world got, we lost. R.I.P. John Belgrave.