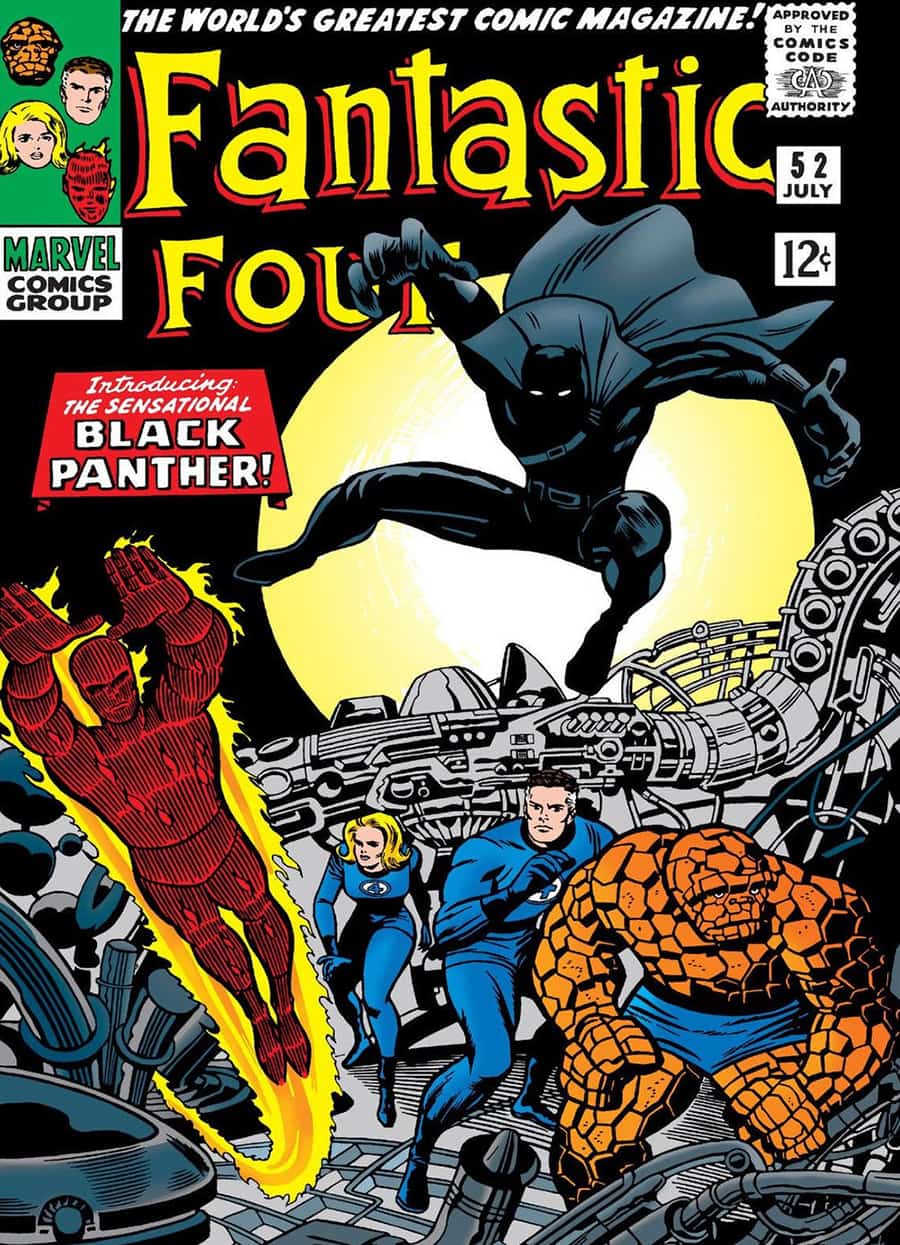

Above: T’Challa first appeared in Fantastic Four 52, cover-dated July 1966.

BitDepth#1133 for February 22, 2018

The Black Panther, T’Challa of Wakanda, isn’t the first black character in comics, but he was the first to be introduced at the very top of the superhero pantheon of any comics company.

He appeared for the first time in the fifty-second issue of the Fantastic Four, one of a group of comics written by Stan Lee that secured the future of the faltering Timely Comics and transformed it into the modern day juggernaut of movie fantasy, Marvel.

The way that Marvel worked then, the overworked Lee who wrote an astonishing number of books for the refreshed publisher, would write captions and dialogue over stories drawn by the first tier of Marvel artists, the most kinetic of which was Jack Kirby.

To a young Trini lad quickly devouring the beaten up Marvel books at his barber’s, the presence of this black man in what had hitherto been lily white fiction on newsprint was a surprise, but his casual confidence and regal aspect ensured that he fit seamlessly into the running soap opera in tights that the creators at the Bullpen were crafting.

The diminutive and pugnacious Kirby drew comics as an assault on the senses. Heroes seemed to leap off the page, surrounded by impossibly complex machinery and under attack by insanely colourful, leering evil doers.

On the cover of Fantastic Four 52, “The Sensational Black Panther” leaps over gouts of Kirby machines and into the midst of the unsuspecting superhero quartet.

T’Challa’s reason for battling four of the most powerful humans in the Marvel Universe to a standstill? To test his mettle against worthy opponents before defending his beloved Wakanda against the attack of Ulysses Klaw.

Lee and Kirby were roughly a third of the way through their landmark run on the comic here, one of the longest pairings of any creative team in comics and it was here that Marvel rightfully earned its boastful title as the House of Ideas.

The Fantastic Four books were crammed with ideas, many of them lunatic and not a little psychedelic – as befits the era – but among this scattershot of notions and partly fulfilled concepts stood the Panther, a keen mind, powerful body and proud ruler of an African nation of technologically superior and largely unknown intellects.

As T’Challa told the four superheroes, he built his super-advanced city on a whimsy, a test of his brilliance, enabled by the wealth and unique properties of the metal vibranium, found only within the borders of Wakanda.

There’s a lot to unpack in that creation. Kirby and Lee famously responded to the dynamics of the 60’s by recreating these stress factors in their books and for angry African-Americans they created a warrior hero from an advanced society in their homeland.

Making the nation of Wakanda isolated and invisible was a ploy they regularly used to align their colourful fantasies with the mainstream realities they were notably successful in merging them with.

It would be decades before another publisher would muster the daring to introduce a fully formed black character to what was presumed to be an overwhelmingly white audience.

Marvel itself fell back on stereotypes to create Luke Cage decades later, enmeshing him in prison, criminal misunderstandings and Tuskegee style chemical experimentation on downtrodden people of colour.

But there was no hollering of Cage’s “Sweet Christmas” for T’Challa. He didn’t have to fight for his place among white peers or even gods and aliens slumming it on planet Earth. He arrived fully formed and magnanimous with his authority.

And if, in the future he would be beaten down and run through a wringer in the service of conflict and plot, he would remain what he was right from the start, royalty in aspect, in thought and in deed.

Seven years after his introduction to the Marvel Universe, the Black Panther would be revisited, this time by another creative team led by Don McGregor, who put the Wakandan king through a 13 issue test of character focused on archvillian Erik Killmonger, now known collectively as Panther’s Rage.

McGregor, who never saw a comics panel he couldn’t fill with words, created a new form for comics storytelling with the work. Before then, stories might run for two issues, perhaps three, but that was it.

For this journey into his heart of darkness, McGregor crafted an episodic series of conflicts, each of which led to the next, introducing a style of storytelling that would eventually become the comics miniseries, formalised with DC’s Camelot 3000 and finding its creative apex in Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen.

Eventually, black talent would put their stamp on the character. Billy Graham was the artist on much of McGregor’s run writing the book.

Christopher Priest’s work on the book was aggessive and polarising.

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Panther was a conceptual refreshing and realignment of the basic principles of the comics version with the one that would soon appear on screen.

Chadwick Boseman’s robust introduction of the character as a live-action player In Captain America: Civil War and the calculated release of powerful imagery of the cast have fuelled robust interest in the film.

But those efforts stand on the shoulders of courageous storytelling that established a black character that for many years was sui generis in the world of comics, a man who said it loud without every having to say anything more as he stalked the panels of Marvel’s publications.

Now, his turn has come to do the same for Hollywood.